Venny Prohibition: will Trump D.A.R.E. to do it?

The Trump administration is considering a ban on some or all Venezuela/PDVSA bond trading, and now bondholders are leaving the market while they still can.

In the hardy crew of risk-tolerant traders specializing in Emerging Market ‘High-Beta’ fixed income —the riskiest, most volatile and speculative bonds of the Emerging Markets world— the Venezuela bond (“Venny,” in the lingo) dealers are consistently among the most active. Investors dabbling in these bonds are addicted to the core. There’s just nothing like it, in terms of returns.

So, what would happen if the drug they’re all hooked on was removed from the market overnight? Once seen as an impossibility, this scenario is now front-and-center, after the Wall Street Journal reported two days ago that the Trump administration was possibly considering taking Vennys out of the New York Market as part of a sanctions escalation on Venezuela. Bloomberg is reporting that fresh sanctions will come today — it’s not impossible this could be one of them.

How draconian the measure might be is still up for grabs. Administration officials are reportedly considering either,

A) A temporary ban on all Venezuela/PDVSA dollar-denominated bond transactions by US entities that

or

B) A permanent trading ban on the most recent debt issues; specifically, the PDVSA 6% 2022 Hunger Bonds (aka, ‘P22n’) and/or the VENZ 2036 (aka, ‘V36’) notes issued through chinese brokerage Haitong Securities.

Scenario A would amount to a draconian ‘nobody gets in, nobody gets out’ of the market from the day sanctions are effective. If you’re left holding Venny bonds when such a ban comes in, nobody in the States would be able to give you a legal way out of your position. High uncertainty is guaranteed in this scenario. “This would be a new step for Treasury and there would undoubtedly be collateral damage for U.S. institutional investors”, according to the analyst of BlueBay, a prominent UK investment firm covered by the Journal.

Scenario B is a more surgical approach. The bonds involved are the shadowy VENZ 36s we’ve written about in the past: they were privately placed in the books of Banco de Venezuela, and have never been sold for cash. By banning their trade, the U.S. could stop the Maduro regime from borrowing fresh money through lightly disguised ‘secondary-market transactions’, while trying to minimize the impact on the rest of the Venezuelan debt market and shielding legitimate investors (which are not providing fresh money to Maduro & Co.) from unnecessary losses.

Already, the operation has given some market participants the heebie jeebies: “I would not touch them with a 10-foot pole”, said the chief investment officer of a Greylock Capital (a US hedge fund), when asked about his thoughts about the P22n, another one of PDVSA’s ghost issues.

Either way, the measures would be the first step against the Venezuelan financial system since Trump promised “swift economic action” against Maduro & Co., in retaliation for the Constituyente and the myriad of dictatorial excesses that have followed it.

Already, the operation has given some market participants the heebie jeebies: “I would not touch them with a 10-foot pole.”

What’s less clear is the impact that such measures may have on the stability of the regime and on financial markets. Nonetheless, some in the market have decided to just jump to a conclusion: THIS IS THE END!

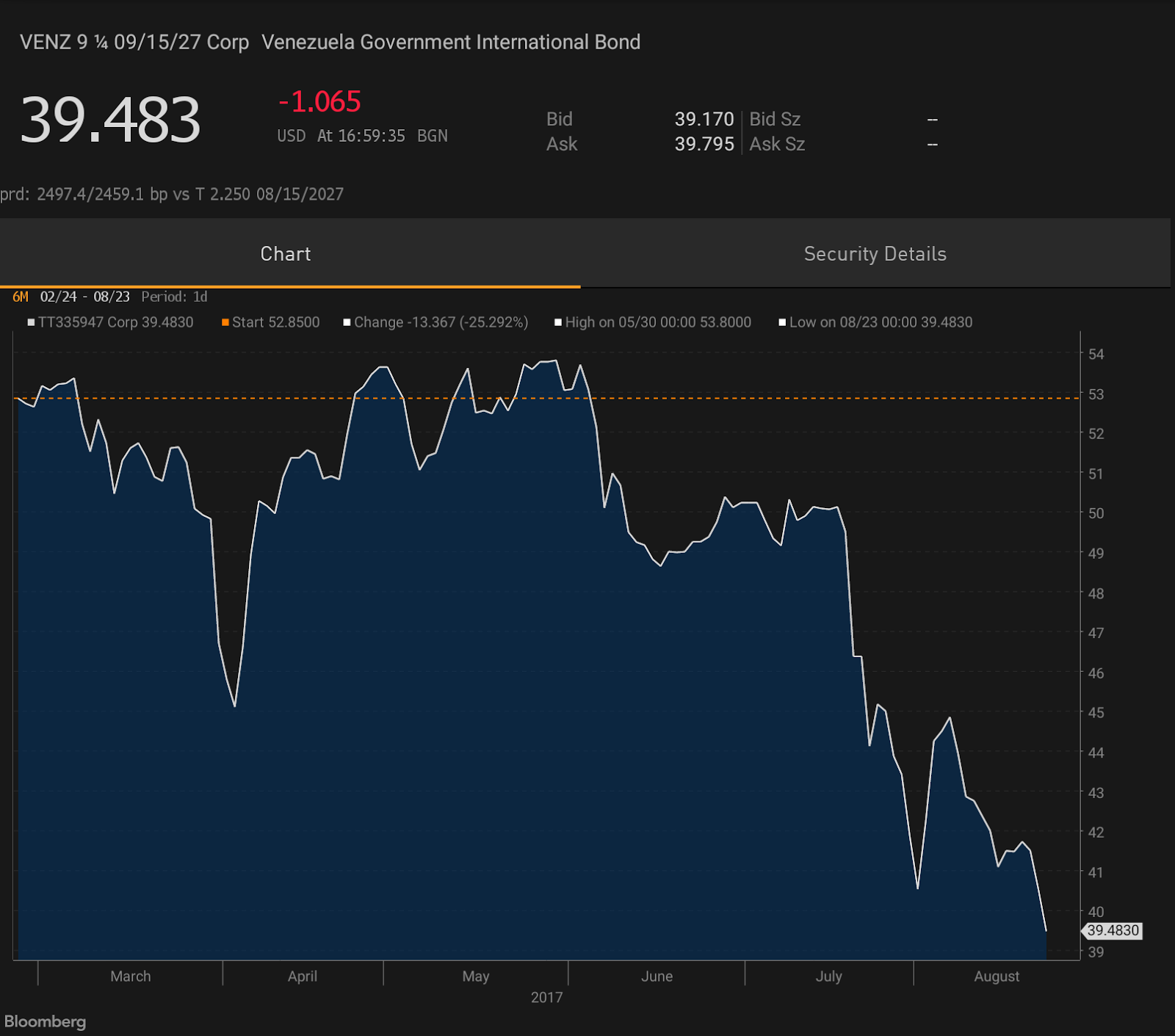

Bond prices went down by a point in the aftermath of the WSJ piece and now sit near 18-month lows as everybody seemed to be hitting the sell button first and asking questions later. It makes sense: if you don’t get out now and a trading ban comes in, you’re left holding a bag of smelly bolivarian turds.

And the expectations game isn’t helping: if Trump does impose a trading ban now, why wouldn’t he just go full-out oil blockade a little later? In such a scenario —the implications of which were already priced by the market and covered by CC last month— a credit event (as in, a ‘sh*t hits the fan’ event) in the near term is more or less certain.

Some bulls might say that it ain’t over; bonds bounced back yesterday over anonymous reports of an alleged ‘debt buyback fund’ organized between China and Venezuela that would seek a way around paying the bonds maturing in 2017 and 2018. Leaving aside what this new initiative may imply for the debt market (that’s meat for a whole new post), we can be certain that the geopolitical implications of any sanctions taken now are yuge; Trump would have Beijing as a big loser of a general trading ban, making such a decision much more costly and complex.

The government’s ability to pay, already compromised and almost entirely dependant on ‘backdoor’ external borrowing, would be in even worse shape under a trading ban.

The government’s ability to pay, already compromised and almost entirely dependant on ‘backdoor’ external borrowing, would be in even worse shape under a trading ban.

For one thing, anything that gives the government a face-saving way out of continuing to pay may lower the political cost of default. Bloomberg had a story on it yesterday: “If it’s the gringos versus Venezuela, maybe their willingness to pay falls”, according to a portfolio manager in Stone Harbor, one of the biggest sharks in the Venny tank. In a way, debt sanctions would make the perfect excuse for defaulting and blaming it on the Imperio.

The devil is very much in the detail here: if sanctions are not carefully drafted, payments themselves could be blocked, leading to a bizarre kind of technical default where the country wants to pay and can pay but isn’t allowed to pay. If the US government were to impose a trading ban, it follows that it could extend to block not only buy/sell transactions, but interest and principal payments as well. Sound far fetched? Sure. But then Delcy is chairman of a Constituent Assembly, how far fetched would that have sounded to you in February? Plus, there’s even precedent for this kind of situation: Argentina in 2014.

Quitting ‘Cold Turkey’

Several counterparties have been actively preparing for the worst and putting their own contingency plans in place. Earlier this month, Credit Suisse announced an internal ban to trading the highly contentious P22n and V36 “ghost bonds” we’ve repeatedly written about in the past, as well as any other security issued by a Venezuelan entity after June 1st, 2017. The decision was made in order to ensure that the bank “does not provide the means for anyone to violate the human rights of the Venezuelan people”, as stated in the company memo outlining the ban.

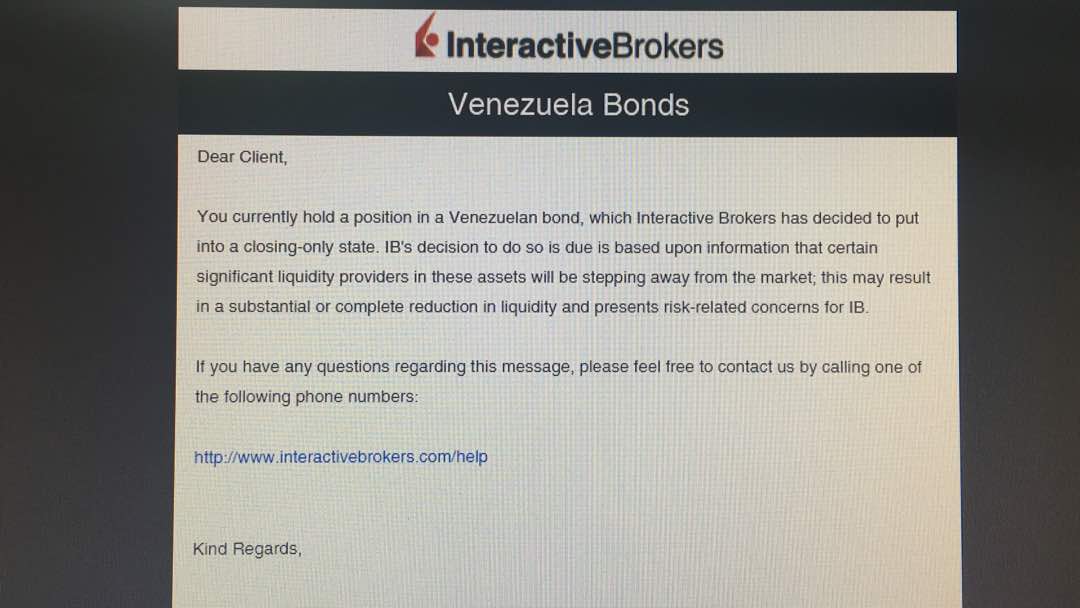

To add insult to injury, the following message has been reported to pop up in the screens of several clients of US-based Interactive Brokers:

The costs of just saying NO to Vennys

The costs of just saying NO to Vennys

A broad-based trading ban would face real difficulties politically at home. So many Wall Street players have been making so much money on Vennys for so long, the temptation to circumvent the ban will be strong. You can imagine banks discretely directing their trades through offshore vehicles, creating a ‘grey’ or ‘black’ market for Venny bonds that would leave us with a less transparent market that carries greater transaction costs for investors. Worse, the restrictions could leave the whole market up-for-grabs, empowering organized crime groups to take a leading role at the Venny casino at the expense of the mainstream investment community.

If you outlaw Venny trading, only outlaws will trade Vennys.

A broad Venezuela debt trading ban would imply sizeable losses for all Venny investors, even if they’re not supporting Maduro directly. A ban wouldn’t restrict the government getting help from its Russian or Chinese allies.

In my view, a broad ban over all VENZ/PDVSA bonds currently in circulation is not feasible, nor is it obvious how it would hurt the Venezuelan regime. Brutalizing secondary market investors who never have and never will put a penny in Maduro’s pocket would be a very strange way to go about this whole thing.

A broad Venezuela debt trading ban would imply sizeable losses for all Venny investors

The much more likely strategy is a more narrowly-focused ban on the PDV22n and VENZ36 bonds. Targeting these ghost bonds —which are obviously politically tainted and have no proper legal basis— would concentrate the costs on the regime while minimizing losses to Wall Street.

By the way, if you wondered what this all means for the average Venezuelan back home, the answer will be somewhere between “un carajo” and “nothing at all”. Or maybe it does.

It’s all about how the country has turned into a high-stakes casino run by The Big Forks, and how the rest of the nation is immersed in an unprecedented, never-ending collapse. The government doesn’t care or fear for anything other than the specter of the casino being forced to shut down for good.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate