Mangokistán Chronicles

In one famously combative corner of Ciudad Guayana, the entire community has come together – from everyone’s aunt to the kids in protest gear – with one simple goal in mind: to keep the roads closed until the government falls.

The severed tree branches blocking the road and the burned down bus confirm I’m in the right place.

I want to take pictures, but I don’t want to set off any alarms.

I’m in a street sandwiched between buildings and I feel watched.

It’s better to wait for the guys to turn up. I have some idea about how they work, they get a lot of help from the community, and they keep each other informed using a WhatsApp group. Someone is likely looking out from a balcony. I don’t want them to think I’m some SEBIN guy taking pictures.

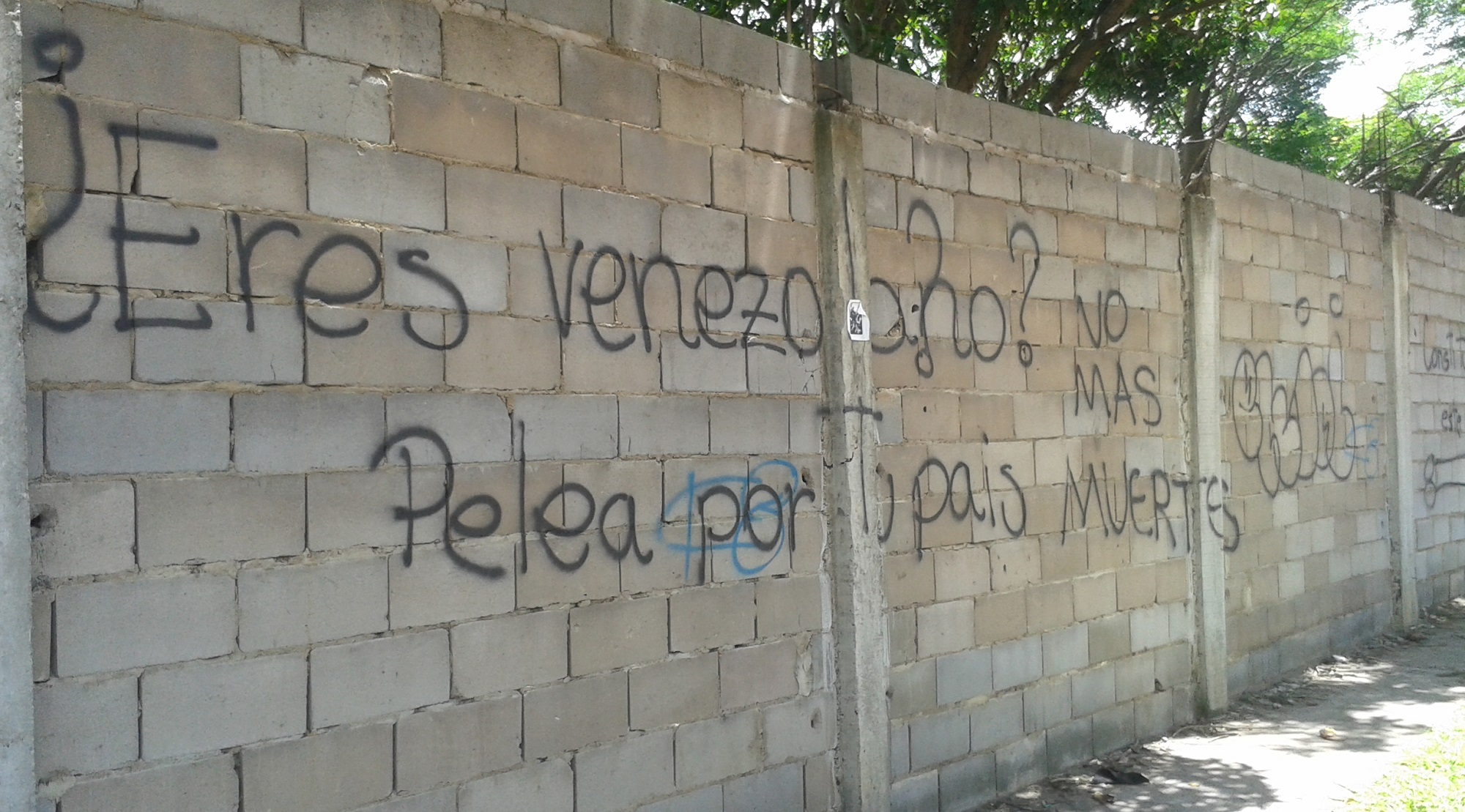

I keep walking, trying to make sure not to trip on any steel cables. The cables are set out from the body of the burned out bus to the trees and back, but the sidewalk is relatively clear. Just a few broken bottles, tree branches, spent tear gas canisters here and there. I see some discarded homemade shields a bit away. A graffiti on a wall reads “¿Are you Venezuelan? Fight for your country. No more deaths.”

I feel like I’m in a battlefield where everyone somehow vanished. In fact, I’m inside a middle-class housing development in one of the hotspots of the protests in Ciudad Guayana. They’ve been at this for 91 days. On GoogleMaps, it says this place is called Los Mangos, but these days everyone calls it Mangokistán.

I was here the day before, I came to talk to the chamos and to ask for permission to write about this place. I talked to 5 hooded kids, and they took a picture of my ID and asked me a bunch of questions before deciding to open up.

But that was yesterday. Now the minutes drag out, and I’m feeling more and more vulnerable. 15 minutes later, four hooded protesters turn up. They’re not the same kids I talked to yesterday, so I have to go through the drill again. They want to see my ID and they want to know where I live. Exactly where I live.

Once I get that out of the way I can finally address the elephant in the room.

We were covered by red dots. Snipers were aiming at us from one of the buildings, we ran, y más nunca.”

“What’s the deal with that burned out bus on the way in?”

“They were playing dirty so we burned it,” one of the chamos tells me, from behind his hood.

“How’s that?”

“Well,” he says, “the driver tried to run one of us over, while trying to drive over our barricade. So we took the bus and burned it down.”

“Well,” he says, “the driver tried to run one of us over, while trying to drive over our barricade. So we took the bus and burned it down.”

That was on Wednesday. They had set up a barricade in the intersection, leaving a lane open, and this bus from PDVSA showed up, driving aggressively. They got angry. The day before, the pro-government colectivo groups had shot live ammunition and arrested some of them. They blocked every exit and left the bus moored in front of their barricade. The driver got off the bus and fled, so they set the bus on fire right on the spot. It was a brand-new bus; they think the government actually sent the bus on purpose to provoke them.

It worked.

En la foto se ve a la GNB y los colectivos en Los Mangos. Me informan habitantes de la zona que disparan sin piedad. #Guayana 2pm pic.twitter.com/52oO3LVLlW

— Ligia Maria (@LigiaDelfin) June 27, 2017

#Guayana #28J | Autobus de PDVSA fue quemado en el sector de Los Mangos. Dos tanquetas de la GNB estuvieron en el sitio-lanzaron bombas l- pic.twitter.com/bo4OXqqNYL

— Pableysa Ostos (@PableOstos) June 28, 2017

I’m talking to five of them at this point, under the shade of a tree sitting on a sidewalk. Two of them are putting on the rest of their gear, their helmets and homemade shields. Then they leave, saying “vamos a trabajar.”

“We’re off to work.”

They go to the nearby intersection, where all the traffic lights are broken and the road is partially blocked. I don’t join them yet; I stay with the group for more war stories.

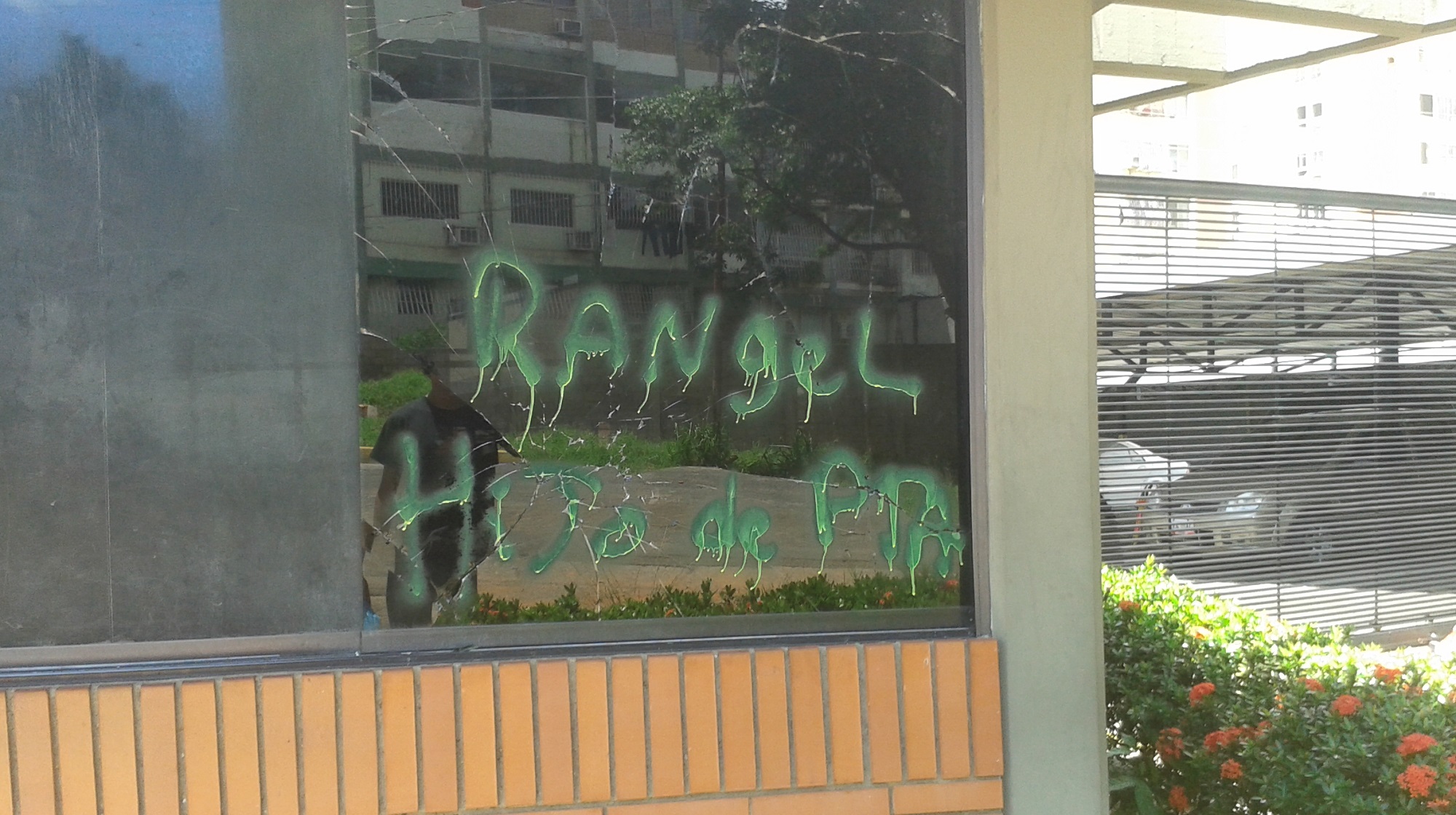

“Mira y… haven’t you tried burning down Rangel Gómez’ cars?”

Loefling Towers is a high-end apartment complex sitting just alongside Los Mangos. It’s an open secret in Guayana that our chavista and notoriously corrupt Governor, Francisco Rangel Gómez lives there.

“We tried once, we threw molotovs at a National Guard truck that was parked there, and the bumper started to catch fire a little. Almost immediately we were covered by red dots. Snipers were aiming at us from one of the buildings, we ran, y más nunca.”

Back in 2014, there were rumors about snipers in Los Mangos, but I never took them seriously. Now I was standing in front of four chamos assuring me they were there and they saw it.

On GoogleMaps, it says this place is called Los Mangos, but these days everyone calls it Mangokistán.

It’s hard to explain the sense of community Los Mangos has, but impossible to miss it if you spend any time there. Now and then, some lady comes and ask the chamos if they need anything, or asks how the wounded are doing.

Recently one of them burned half of his body and blew up his thumb manipulating explosives. A lady just passed by to bring them burn ointment and check on everyone. She tells them: “It says it’s expired, but they say you can use it for a few more months after the expiration date.”

People care about them, and are always bringing them what they can. Most of the time, it’s fruits and juice.

“There are days when we’re down on our luck. We have a breakfast at 3 p.m., but other days we get too much food”.

People from outside of Los Mangos bring them supplies too. The cars can’t get too close because of these barricades, but they just park down the road and open the window. The protesters take turns to get up and get the supplies, with their masks still on.

The barbed wires on one of the barricades actually has pizza boxes hanging on them – a kind of home-made visibility aid to prevent anyone from tripping over it. They remove those at nights, in the hope of catching any colectivo (the paralimiltary) in a motorbike.

I decide to go to the intersection, where there are already six of them collecting money from passing cars. They only restrict one of the lanes on each side of the avenue, and they don’t ask for money, they just stand in there and people give it to them voluntarily. Sometimes they get bags of ice, water, and even some malta.

Now and then, some lady comes and ask the chamos if they need anything, or asks how the wounded are doing.

“The money is to buy materials,” one of the protesters tells me, while he’s working the collection jar. “The mortars cost about Bs.80,000 right now and we’re fresh out. We ran out the day the colectivos came shooting at us, that’s how we repelled them, with lots of fire. Also part of the money goes to buy food, not for us, but for the kids they’ve put in jail. Oh and cigarettes, to bribe the officers so they let the food in. It’s not only about sending them food; we need to make sure the food actually gets to them.”

He’s referring to the group detained in Alta Vista on June 15th, during a MUD march. 11 people got picked up. Alongside others from Ciudad Bolívar, they were sent to El Dorado jail, a dreaded and remote jail located in Venezuela’s far south, straight in the middle of the amazon jungle.

El Dorado is a kind of #TropicalMierda Supermax, designed to keep the worst criminals locked up. Recently, some of those guys were transferred to San Félix. Now it’s easier for La Resistencia in Los Mangos and everyone else to bring them food.

While they’re collecting money, one driver stops to share a few words with one of the hooded protesters. “Plomo con esos malditos,” the driver says, “you gotta go at them with everything when they come, you have to burn those coñuemadres’s asses.”

He gives them money and drives off.

That caught me by surprise. They get lots of donations from passing cars too: food and water, as well as money. People promise to warn them if they see any tanqueta going their way. Others beseech them to take care, to be careful, to watch out for themselves and be safe out there. I figure giving them money is an easy and safe way to protest the government without taking on too much risk. One of the protesters tells me that they do get insults sometimes, but it’s rare. I stood with them for about half an hour, and all I saw was encouraging words.

They had set up a barricade in the intersection, leaving a lane open, and this bus from PDVSA showed up, driving aggressively. They got angry.

I go back to the chamos under the tree, and they’re just talking about girlfriends and stuff, and that’s when the Sensei shows up. The Sensei is one of the leaders, he is a fifty-something guy who gives them instructions. He’s reputed to have contacts within the GNB that tip him off when repression is coming. He joins in the conversation as if he was the same age as them. They were talking about some recent party night where everyone got wasted; he’s totally at ease.

Everything is quiet, the stretch of road between the two barricades transforms into a kind of living room. Nobody much minds the debris all around. One of the guys is sitting on a dusty old pouf telling a story, while all the other are just mocking him for telling tall tales.

BAM!

The sound of a detonation breaks everyone’s train of thought. It sounds like it came from down at the intersection.

“That has to be a shot,” someone says.

Now every boy, and a girl, is running towards the sound to find out what’s going on. Masks, shields, all the gear.

There is some confusion, but apparently, a national guard shot from an APC. They suspect it was rubber pellets – perdigones. Some UCAB students are blocking the road too, up a bit further ahead. The tanqueta found itself in a guarimba sandwich: they couldn’t go back because La Resistencia at Los Mangos was waiting for them, molotovs already in hand.

The forensic exam came right before the tortures. They beat him, but the worst was when they asphyxiated him with a plastic bag, five times.

Two of the protesters ran from the guards to the undergrowth at the side of the street, and they disappeared into the maleza.

They stay there a while, confused, not knowing what to do. No one wants to get stuck in the bushes, or keep the tanqueta trapped for much longer, so they just retreat to the barricades.

Back in the safe-spot, the aunts show up with lunch. Las tías are the ladies from the community who always take care of the kids out here. Every day they bring them food, and they keep them up to date on the information circulating around their WhatsApp group. Everyone gets a little plastic container with pasta with sardines, including me. One of the ladies tells them to not get too comfortable, just eat. “You’ll get to eat around the table once this goes back to normal,” she says.

“There was someone taking pictures this morning,” one of the ladies says, before reminding them to “be careful and remember always to keep your face covered.”

The group by now has 23 hooded young protesters, plus, three tías and the Sensei. The place transforms in a living room again, they talk about torture, and whether or not to go looking for the other two, as they work on their pasta.

When talk turns to torture, they ask one of them to talk again about the day he was arrested. He was on his way to buy burgers when the police came out of nowhere and took him. The forensic exam came right before the tortures. They beat him, but the worst was when they asphyxiated him with a plastic bag, five times. They wanted information about the Sensei, and some of others, but he only knew their pseudonyms.

It’s the famous calle sin retorno. They’ll just keep that street closed until the government falls.

I’m stunned by these stories, but they take them in their stride. “So… when are we going to go get burgers?” They tease each other and laugh it off just like that.

The other two, the ones who had gone missing, then show up in a car, each with a bottle of beer in hand. Someone had seen them on the side of the street and gave them a ride, plus some beers. That’s how much support they get. They chug the beers fast, worried some chavistas might take pictures of them drinking.

When I leave, at about 3:00 p.m., they are just there playing truco. They wanted to cut down the traffic lights to used them for the barricade, but the Sensei advised them to do that at night.

I don’t think the protests at Los Mangos will end anytime soon, unless the government does. They aren’t a think tank, in fact they never talked about politics at all. They didn’t even know the exact date of the Constituent Assembly elections, but they’re pretty clear on their goal. It’s the famous calle sin retorno. They’ll just keep that street closed until the government falls.

The idea is to wear down the security forces. As of day 90 these protesters themselves didn’t seem particularly tired. They apparently can’t be intimidated with torture or even with real bullets. They did the same in 2014, and by now they are very well organized. They have their own intelligence gathering system: people from the top floors of the buildings tell them when the security forces are approaching, they have contacts at the GNB, they are on good terms with the police, and they get lots, lots of support from everyone around them. When the shot was heard earlier three different ladies told me to cover my face and be careful, thinking I was part of La Resistencia too.

In this small community, everyone offers their support however they can. It’s not only the chamos out blocking that street. It’s everyone.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate