LGBTzuela: choosing between the tricolor and the rainbow flag

Life in Venezuela is intolerable in general. For LGBT+ people, hidden forms of oppression and abuse layer on top of the ones everyone can see. To honor Pride Month, it's a silence we're determined to break.

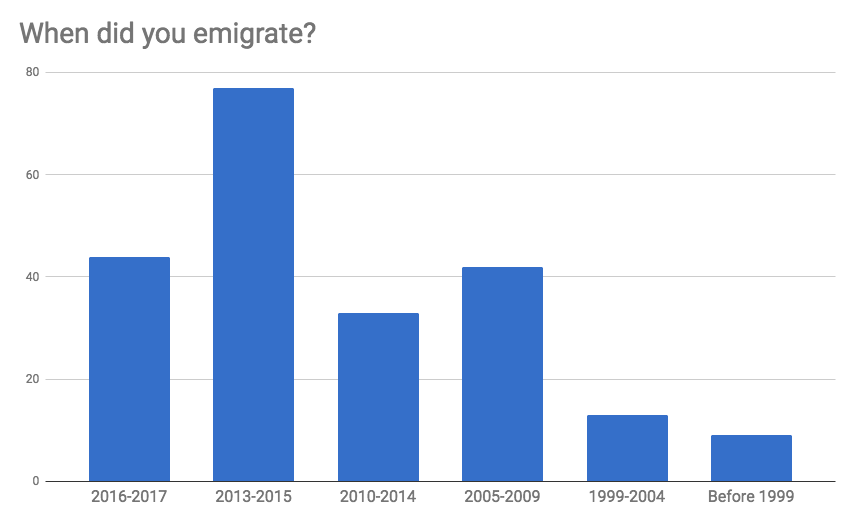

To mark the occasion of Pride Month, we asked LGBT+ Venezuelans abroad to fill out a survey to tell us a bit about their lives and how their identity influenced their decision to leave. We figured maybe two or three dozen people would reply. Instead, 220 of you did. From teens to seniors, living everywhere from China to Panama, from Sweden to Qatar, you were enormously generous in sharing your experience.

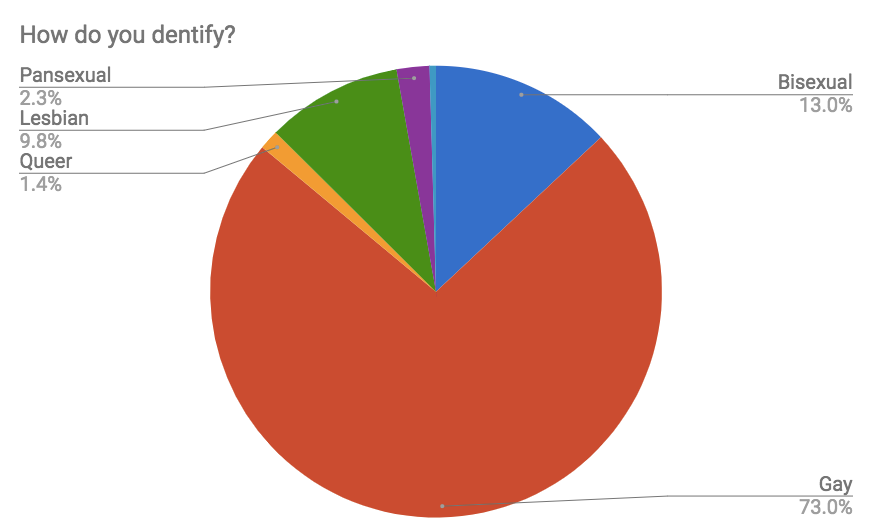

For all the multiplicity of identities out there, the big G ends up being the go-to self-identification. Almost three in four of you identified as “gay.”

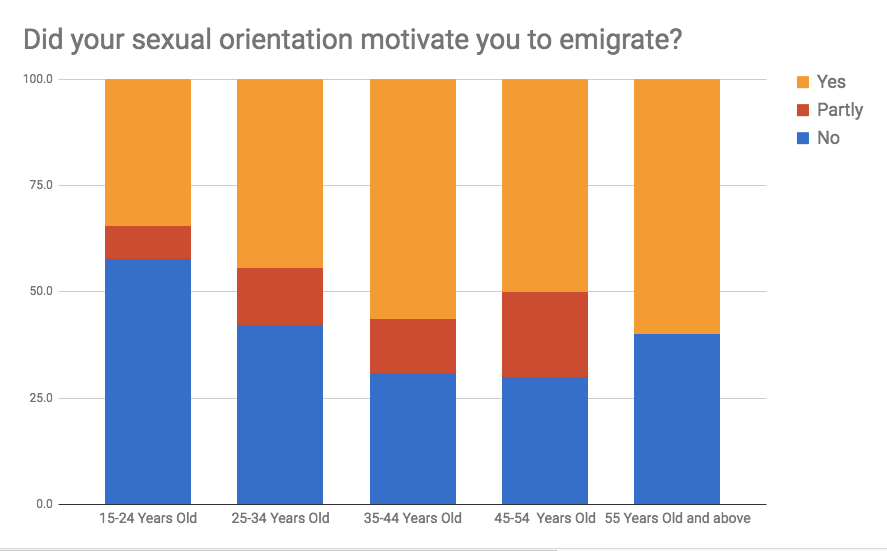

Your sexual orientation was one the main migration drivers only for some of you. Alongside it, the usual litany of impossibilities about living in Venezuela today got cited: crime and violence, lack of opportunities, food and medicines shortages, usual shit.

What’s clear is that the younger you are, the less sexual orientation influenced your life choices:

Despite facing prejudice and little-to-no legal protection, and no serious talk of LGBT+ rights, a few of you had managed to live openly in Venezuela. For most of you, leaving was the way out of the closet.

A startling number of you left in the Maduro era: fully 56% of the respondents left after the departure of El Galáctico…

For many, the experience of migration, while always filled with hardships, was also a discovery of more inclusive societies, of living with a freedom they didn’t suspect. Finding others like themselves, becoming part of a community.

For many, the experience of migration, while always filled with hardships, was also a discovery of more inclusive societies, of living with a freedom they didn’t suspect. Finding others like themselves, becoming part of a community.

For those of you who are used to “keeping it to yourselves,” this was a surprise, one you probably aren’t willing to exchange for anything less than what you have now.

There’s no equivalent in Caracas of Chueca, Christopher Street or La Zona Rosa, though you always hear about Sabana Grande back in the day. Banesco or Pepitos won’t clad themselves in rainbow colors for PR points —TVES at least tried a couple of times— and, as far as I know, there’s no Venezuelan Stonewall. No great unifying event where queer Venezuelans stand together.

Instead, we’ve had fear, violence, rejection, silence, giving way exasperatingly slowly to a degree of acceptance, tolerance and celebration in a few, select circles. It’s no wonder so many LGBT Venezuelans have just left.

To shine a light on this seldom-acknowledged corner of the Venezuelan exile experience, we reached out to different people across the map and ask them a bit about their stories, their desires, and what it means to be queer and Venezuelan.

Some of the interviewees wished to remain anonymous, but their testimonies still manage to give us a glimpse into a reality that, for most, is ignored:

Víctor

Víctor

Everyone is always saying that they knew they were different all along, but I think that only applies to a certain extent. We’re all born and live our early years in a specific environment and throughout our lives, without exception, we go through a process of realizing that we are different to that environment.

Víctor is a doctor living near Madrid. Back in Venezuela, he had to go through endless late shifts, lack of resources and the harassment of malandros in one of the country’s largest public hospitals.

In Spain, his life couldn’t be more different.

“Crisis or no crisis, I think I would have made the same choice.” It was only many years later, once he was living in Madrid, that he got to live his attraction to men more freely and came out to his family. Their reaction wasn’t positive, and the wounds have, as he says, “taken years to heal.”

Though he’s open to his friends, he admits he tends to keep it to himself. After all, in many instances, Spain is not quite the paradise of acceptance many like to imagine. Still, it’s miles ahead of Venezuela.

“At least you don’t see here people setting up a witch hunt to figure out who’s the mandatory ‘office faggot’ so they can ridicule him,” he says

Transphobia and homophobia are as harrowing in Venezuela as they are everywhere else. Its effects are often deadly, from trans sex workers killed in Avenida Libertador to young people burned alive just for not being straight.

In Víctor’s opinion, what really gets to you, though, are the microaggressions, small hints and side comments from so-called tolerant people that are always “making you doubt yourself,” which most people don’t notice.

“At least, here you don’t see people setting up a witch hunt to figure out who’s the mandatory ‘office faggot’ so they can ridicule him,” he says.

For him, his rights aren’t just an issue among many. It’s all one interconnected issue and facing it means not just changing the structure, but also the people. As he puts it,

Venezuela is in a deep crisis and the social and legal situation for the LGBT+ population is part of that crisis and that requires work, same thing with shortages, crime and others problems. You can’t just solve it by dealing with one problem at the time.

Some shift has happened, that’s undeniable. Movies like Azul y No Tan Rosa, Pelo Malo, Liz en Septiembre and Desde Allá show that queer voices in Venezuela not only have lots to say and in very powerful ways. They are also recognized and celebrated at the Toronto and Venice Film Festivals and win Goyas and the Golden Lions.

We have openly gay personalities like Boris Izaguirre and Gisela Kozak. We’ve elected Tamara Adrián, the first transgender MP in South America despite some religious protestations, and the TSJ finally said they would look into changing name and gender in public records.

But these feats feel small and overdue compared to other countries across the continent, including some governments that were, at the time, allies of Chavismo. What’s their excuse?

The Chavista tragedy has been the perfect excuse to avoid advancing our rights.” Víctor says, joking that LGBT+ rights are obviously a first world problem, “just like a working healthcare system and fighting corruption.”

Despite his bitterness about Venezuela, something shared by many regardless of orientation, he has a clear picture of how things should be, “we have to end violence. As long as the goal is to get rid of others instead of understanding each other we are all moving targets since we are all ‘others’.”

Teresa

I realized it when I was in fourth grade, I think. I felt a certain affinity for people of my own sex. I thought that was common. As I grew up, I understood I was different from the others.

Teresa is a lawyer, currently living in Chile. Like so many others, she has found in her new home the tolerance and peace of mind she couldn’t find back in Venezuela.

My life is now different because the country where I live now has an inclusive mentality and people are used to seeing it as something natural. I’m not constantly in fear of my parents seeing something they don’t like, even though they’re fully aware of my identity.

Despite the contrast to her previous life, Venezuela remains in her thoughts. Back home, she was your quintessential opposition comecandela protester and, in Chile, she’s no different, despite having to keep her orientation private from her fellow activists.

Living throughout what is probably its worst crisis since the Federal War, it’s easy to dismiss LGBT+ rights in Venezuela as as secondary concerns, thinking we first must focus the most urgent problems.

But despite all these disadvantages, Teresa still hopes to return to Venezuela in the future.

But depending on whose numbers you believe, anywhere from several hundred thousand to a million or more Venezuelans get to add homophobia to the unmanageable list of problems Venezuela throws at you on a daily basis. Social solidarity —so crucial to survival amid the crisis— is withheld. Job opportunities close out —as though there were that many to begin with. It all adds up.

I ask Teresa if she thinks it’s a mistake to talk about LGBT+ rights in Venezuela at the moment and she gives me an answer only a lawyer can:

I don’t think it’s a mistake. The restitution of the rule of law in the country, must mean the restitution of inherent rights, such as the freedom to love. To build the country most Venezuelans want, that must apply to everyone. The general right to be and to act with the same liberties. If we have the right to express ourselves, then why we don’t have the right to express our love?

Chile, while far from perfect, offers civil unions, legal name and gender change —albeit surgery is required— and explicit protection against labor and housing discrimination. Venezuelan laws, in contrast, are mostly vague or nonexistent on the subject. And when the mechanism exists, the authorities simply might choose not to exercise it, which for years has been the case many trans people deciding to change their name to match with their identity.

But despite all these disadvantages, Teresa still hopes to return to Venezuela in the future.

Above all, Venezuela is my country; my roots and my essence are there. I would love to return and feel the same liberty and solace that I feel here. But things have to change for me to return.

And what does she want?

Where I currently live, civil unions are allowed with the same rights as marriage and, well, my partner and I want to start a family. If this is legalized in Venezuela, we would happily return to our land.

Same-sex marriage has traditionally been the hot-button issue regarding LGBT+ rights, since it means an equal footing before the law with several organizations and initiatives in the past focused on it. Despite their efforts and small gains, it doesn’t seem that Tersa and her partner will be able to come back any time soon.

Jess

I was 2 years old when I realized that my way of being didn’t fit what others expected of me. I arrived at my daycare center with Aladdin’s shoes instead of Jasmine’s, like the girls over there. They noticed it. That was the first time I was bullied because of my masculinity.

Jess is a 28 year-old public relations professional living in San José, Costa Rica. Though not originally part of his plan, circumstances forced him to make this country his home, and for this he has nothing but gratitude.

Like so many trans people, he’s had to face something of a double closet as he struggled to understand his identity. First he thought of himself as a lesbian and then, last year, after a life of pain, he came to the realization that he was a queer trans man. This year he starts hormone replacement therapy, which soon will be provided by public hospitals in Costa Rica.

Jess says that while his father was very supportive every step of the way, his relationship with his mother was strained. “My mother made me repress my masculinity and attraction to women until I was 23, when she kicked me out of the house.”

Beyond the standard-issue challenges gays and lesbians face, trans people face obstacles all their own, often in terms of accessing medical care and legal recognition of their identity. They face prejudice, exclusion, and even violence that prevents them from leading a fulfilling life; in some cases they have been cast aside and discriminated by groups of cisgender (non-trans) people within the queer community.

It has happened to me, especially since I realized I’m a trans man. Sometimes, due to machismo, they can’t understand me, accept me, or respect me as a man because I have a feminine body.

But even before his realization, things were tough for Jess in his professional life.

I was the leader of a crew and we had a special event at the end of the day. They told us we should dress in formal wear. Although I was still in the closet and living as a woman, I dressed in a blazer, suit pants and flats. We had a planning meeting and from the moment I stepped in, I was the target of mockery because of my clothes, which kept on happening throughout the rest of the day.

Transphobic violence tends to target women and feminine-presenting individuals, but this doesn’t mean men like Jess are exempt.

“When I sent a complaint to Human Resources,” he says, “they told me they couldn’t do anything about it.”

Numbers on trans people in Latin America are dire, over 75% of all recorded transgender and gender-diverse murders worldwide happen in the continent, with Venezuela in the top five. 65,5% of all reported LGBT+ murder victims in Venezuela were trans people, most of them trans women forced to be sex workers due to lack of opportunities.

Transphobic violence tends to target women and feminine-presenting individuals, but this doesn’t mean men like Jess are exempt. Just earlier this year a trans man in Aragua was reportedly beaten by two police officers while others watched, doing nothing.

I think the crisis is very intense but that also, it’s a human rights crisis. While Latin America has taken great steps forward by recognizing the human rights of the LGBTTI population, Venezuela has gone backwards. Dealing with the crisis also means dealing with these problems: they are part of it.

He simply doesn’t see any of these changes coming to Venezuela in the near future, less so this becoming a safe place for him.

As a queer trans man, there must be a deep change in government policies, one that doesn’t create conditions that allow discrimination or violence against my gender identity or sexual orientation, one where I could be part of the job market, legally change my name and gender, have access to the medical attention I require as a trans person, and overall, have quality of life and the chance to manage my life plans.

Jess simply wants the same as Víctor and Teresa. The same than everyone else, really. Laws that guarantee his protection, opportunities for work and education, access to basic healthcare and other social service adequate to serve his needs. A future.

And above all, respect for who he is.

Living in Venezuela is hard to begin with, and for the LGBT+ community the hardships are compounded in ways that can be invisible. Staying closeted becomes a survival strategy. It’s hard enough to survive without facing yet another form of oppression.

Homophobia in Venezuela is normalized — it slips seamlessly into the fiber of every day life. The easiest way to insult someone? Question their sexuality, something both chavistas and opositores do with ease. The easiest way to get a laugh? Gay jokes. The popularity of characters like Charly Mata —with a longevity unheard for most comic characters— and Los Fabu Fabu show not much has changed in this regard.

Even tío Simón did it back in the day!

Is it any wonder so many LGBT+ Venezuelans end up throwing in the towel and moving abroad?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate