The Palacio Municipal’s Tinsel Crown

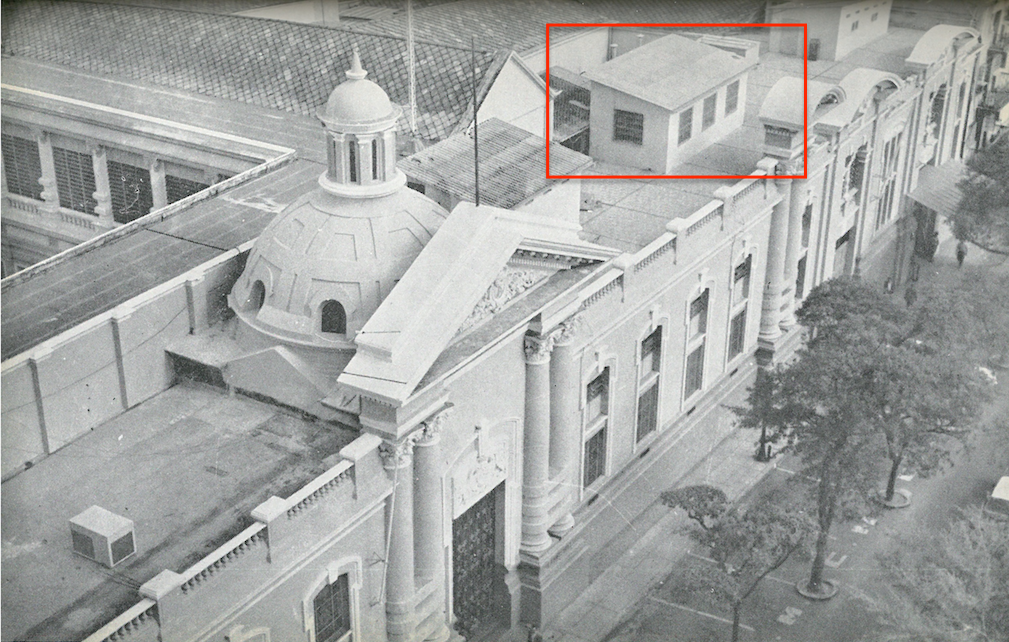

When Mayor Jorge Rodríguez decided to slap a tacky Salón de Fiestas onto the roof of the 344 year old Caracas City Hall, architectural purists were appalled. In fact, his is just the latest in a four-century history of non-stop desecrations.

From its inception in 1673 as the Colegio Seminario de Señora Santa Rosa de Santa María de la Ciudad de Santiago de León de Caracas, the building now known as the Palacio Municipal (City Hall) has known all sorts of revolutions and makeovers.

Of the revolutions, the most famous the building witnessed was certainly the signing of the 1811 Declaration of Independence: Venezuela’s break with the Spanish gold crown was launched from its chapel. Of the makeovers, the rooftop reception hall put up late last year by Mayor Jorge Rodríguez is the latest —and to some the ugliest— but very far from the first.

A lesser known fact is that this Seminary College would turn into the precursor institution that, over the course of two hundred and fifty years, would give rise to both the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the Universidad de Los Andes, charting the country’s evolution from religious to secular education.

One of the stalwarts of this transformation was Simón Bolívar, who not only contributed to the College’s eradication of racial and class prerequisites through the 1827 Republican Bylaws of the University, but also donated several of his family’s haciendas to help the former Real y Pontificia Universidad de Caracas, by then relocated to the San Francisco convent, gain financial autonomy.

But our topic today is the Palacio’s physical makeovers. Of these, it has known plenty. I’m indebted to professor Francisco Pérez Gallego for directing me toward the fascinating work of a Caracas chronicler of yesteryear, Juan Ernesto Montenegro, whose enormously erudite and amusing La Capilla de Santa Rosa de Lima: Fragua de la Universidad y de la Libertad (1977) describes how this structure managed to survive accidents, fire and the 1812 and 1900 earthquakes.

It hasn’t, alas, been able to escape the ravages of men, who not only have repeatedly concealed it, but also “mutilated and decapitated” its frontispiece and bell tower in 1875.

Odd additions to the Palacio Municipal’s roof: as caraqueño as a Pastel de Polvorosa.

(This building) would give rise to both the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the Universidad de Los Andes, charting the country’s evolution from religious to secular education.

In 1906 Alejandro Chataing extensively modified and expanded the building. But more radical intervention was to come: the Palacio was “turned around entirely” in 1948, as another city chronicler, Enrique Bernardo Núñez, decried when the Palacio’s northern entrance which had always faced out onto the Plaza Bolívar was switched to its western façade, opposite the Palacio Legislativo.

In order to protect the building from any more such drastic makeovers, it was designated a Historical Monument in 1979.

And yet, this august municipal institution witnessed a return to 19th century antics late last year, when mayor Jorge Rodríguez decided it would somehow look better with a Salón de Fiestas on its roof, since apparently the musty old Seminario didn’t have a good spot for him to maraquear un whiskey until then.

In a country where the boundaries between the public and the private have always been tenuous, the res publica, or common good, is ripe for the picking and open to use and profit from or, alternatively, destroy, litter or vandalize at will. The distinction between the State (charged with protecting public property) and its temporary administrators (the government that happens to be in power) is equally blurry. It comes as no surprise, then, that officially defacing or distorting the res publica should happen as a matter of course.

True, doing as you please despite its consequences is so chronic and widespread that improvisation can be considered the only genuine national modus operandi. It happens at all levels and hinges on only one condition: getting away with it.

Architecture is a prime example. Haphazard, ad hoc and often amazingly creative, a large percentage of the built environment in Venezuela is spontaneous. The extensive informal architecture that covers the hills of Caracas (over fifty-percent of the city’s total construction), combines with the widespread phenomenon of personal interventions on existing structures to create an anarchic, eclectic urbanscape entirely Made in Venezuela.

It hasn’t, alas, been able to escape the ravages of men, who not only have repeatedly concealed it, but also “mutilated and decapitated” its frontispiece and bell tower

This mode of architectural adaptation is deployed by all social classes, and consists of creative strategies to make the uninhabitable habitable, to render the impersonal personal, or just to stake out a territorial claim. From mind-boggling rancho condos, where each generation adds a new level in its own distinctive style; to the popular addition of clothes lines, air conditioners or satellite dishes in middle-class buildings; to the willful extension of historical buildings, nothing stops Venezuelans from doing as they please with their habitats, workplaces or, in the Palacio Municipal’s case, the downgraded res publica.

So while some expressed horror at Rodriguez’s “desecration”, personally I think it was quite consistent and predictable. The mayor wasn’t really defacing our heritage: he was honoring our ongoing dysfunctional relationship with the tormented building, inscribing yet another act of institutional violence upon it by using the common good as a personal territory at the expense not only of what it stands for, but more importantly, who it belongs to – the people that governments supposedly work for.

Now, if you don’t care about any of this and decide to throw all regulations to the wind the moment you have open access to the res publica, you might as well go all out and be bold, be playful, make a statement. Why stop at a lame Sala de Fiestas when you could build something on the scale of the new Panteón Nacional, where whatever is left of Simón Bolivar’s bones must have disintegrated from so much turning around in this huge grave-cum-skateboard-ramp, fit for King Kong?

Take a cue from the prolific Venezuelan imaginario and do something worthy of the myriad satellite dishes and seven-floor rancho condos. Don’t add insult to injury by crowning a pastel-pink neo-classic building with a symmetrical, modern extension right out of an IKEA box. That’s boring and anticlimactic, completely unfit for the radical gesture of taking over the public good.

Take a cue from the prolific Venezuelan imaginario and do something worthy of the myriad satellite dishes and seven-floor rancho condos. Don’t add insult to injury by crowning a pastel-pink neo-classic building with a symmetrical, modern extension right out of an IKEA box. That’s boring and anticlimactic, completely unfit for the radical gesture of taking over the public good.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate