Viva la Vinotinto, or Protesting from the Bleachers

I was among the Venezuelans who somehow made our way to a stadium in the far-off Korean city of Suwon hoping to witness a miracle.

The cameras were all – justly – focused on the players on the field, but if they’d been turned the other way, you had all the makings of a blockbuster documentary. The closer you got to Suwon station, the more Venezuelans – clad in vinotinto shirts, speaking the s-less Spanish of the Caribbean – you saw, and the more random people wearing their vinotinto shirt would walk up to you and shake your hand, exchange some words.

For Venezuelans living in East Asia, seeing many of us gathered in one place in the middle of nowhere felt exhilarating.

“¿Y tú de dónde eres?”

There I was, 17 years in exile and counting, and in Korea by way of the academy after living in four others countries. There was a couple that had just arrived, they were “fresquitos” in exile, just 4 months out of Venezuela, living some hours away in Hong Kong and asking around to see if conditions might be better in Shanghai or Singapore.

There was the little kid running around whose parents told us: “We live in Pusan, and he was born in Germany, pero él es Venezolano.” There were others from the U.S. West Coast who came hoping to witness a miracle, looking a bit surprised to see so many of us here, “en este continente de chinos.” There was the living-in-China contingent, by my count the one largest in number, Venezuelans who through the chavista debacle somehow ended up living in Shanghai, Beijing, Chendu, Xian, Dalian, and who had come on such a spur-of-the-moment jaunt that some of them still had not fully thought through their excuses for when they would walk in super late to their jobs back in China come Monday.

I personally spoke with a couple who had come directly from Maracay, Venezuela. They decided that they just had to see this one game the moment the Venezuelan youth team had defeated – on penalties and at the last second – Uruguay to claim a berth in the final.

So many of our voices there, so many Venezuelans living abroad, or – like I heard a Venezuelan say – sobreviviendo aquí en el exterior.

For Venezuelans living in East Asia, seeing many of us gathered in one place in the middle of nowhere felt exhilarating.

Venezuelan flags were waving all over the place – both the 7-star version and the 8-star version. The whole night was interlaced with chants against the Venezuelan dictatorship, and not even once did I see, or hear, or even suspect, any of in the Venezuelan crowd being sympathetic to the government.

The third place game and the final were played back-to-back, with a single ticked good for bith events, so after the Uruguay-Italy game we headed en masse out to the stadium’s entrance. Someone had heard that DirectTV was going to shoot a pre-game interview with the vinotinto fans. We were all chanting and drinking and jumping and singing, and the Korean locals looked at us with wide-open eyes and some even joined in to our chants. We heard Koreans take our cue and sing our Somos vino tinto chant with the same glee and good cheer we all had. They later went on follow us in our chant of ¿Quienes somos? ¡Venezuela! ¿Qué queremos? ¡Libertad!

There was both irony and joy in seeing these locals join us, unknowingly, in our chants for freedom.

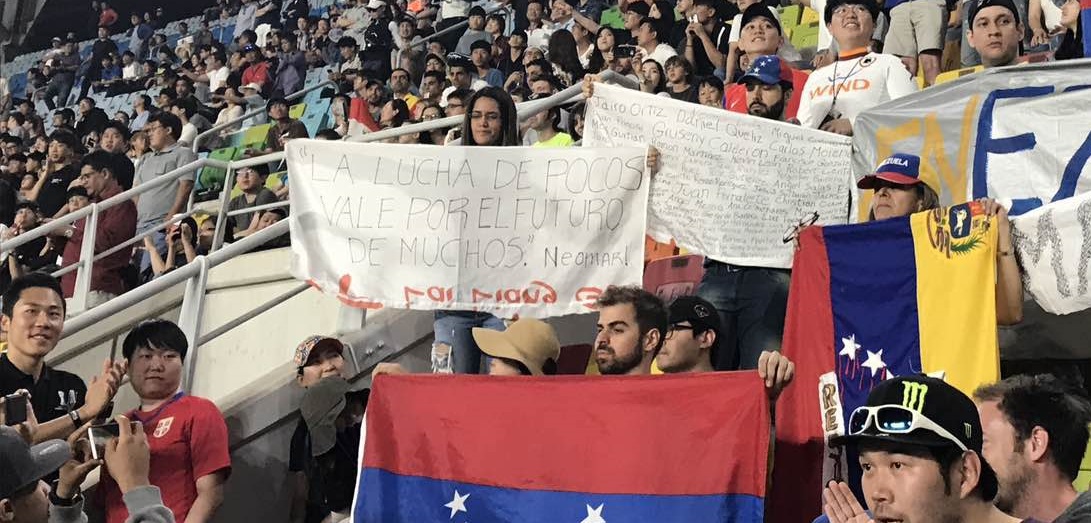

Some of the most spirited, inspired, and brave among us made it a point to bring protest banners – along with our flags and our shirts and our voices. One read “SOS Venezuela.” Another one, “Libertad.” The one that by being the simplest held to me the most power – was just a piece of white cloth that waved sandwiched in between two Venezuelan flags. It looked like the white banner held by Lady Liberty in Delacroix’s painting. On it were written all names of people killed in the anti-government protests so far this year.

It got waved around guerilla-style.

FIFA rules forbid the display of political banners during soccer games. Increasingly, a nervous-looking group of FIFA staff came to our side of the bleachers, walkie-talkies in hand and a suspicious look in their eyes.

The whole night was interlaced with chants against the Venezuelan dictatorship.

They would hear us singing chants in Spanish, surely wondering if these were songs in support of often-unsung or undersung national heroes, or if they were indeed the chants of an anti-government terrorists, or separatist, or God-knows what kind of dissidents from this unknown banana republic. It was an all too alien sight even for the British fans, who were surprisingly quiet.

Somehow, in a stadium full of limeys, we were the hooligans. And as the game went on, we became increasingly defiant.

Not once, but three times, FIFA staff came to our side of the bleachers and tried to take away our protest banners. They pointed at the flag with the names of the fallen and asked “What does that say?” Viveza criolla kicked in and someone said “these are the names of the players,” or “these are the names of all of us who came to watch the game,” they were met with more suspicion by the authorities.

All the flag-waving supporters wanted was for the broadcasters to focus their cameras on them, even for a second, perchance by accident. But I doubt it happened. Eventually, after a couple of failed attempts, FIFA staff brought in their biggest man, a tall and portly fellow who would not be out of place becoming the newest Korean-born Yokozuna. This guy was huge. He climbed up to where the most “offensive” of these banners were being flown. There was the beginning of a physical scuffle when the FIFA wrestler made no attempt to be polite: the political flag had to go.

Ajá, se prendió este peo.

But somehow, the brave Venezuelan lady who had made the flag managed to keep it, to wrestle it away, after much back-and-forth with the FIFA man.

All the while, tensions were running high. Venezuela was down one goal, and we had missed a penalty. It seemed that everything was lost, and now they were even taking away our banner in memory of our dead and in condemnation of the dictatorship. No joda was the mood of the crowd now.

They would hear us singing chants in Spanish, surely wondering if these were the support songs of an often-unsung or undersung national heroes.

Eventually, tired out by the tug-of-flag, the FIFA flaks called in the cavalry. The FIFA staff disappeared, and the actual police turned up.

But this was not Maduro’s police force. Strangely, they seemed even more conciliatory that the FIFA corporate muscle. They were young, barely into their twenties, calm, and willing to talk to the people waving the flags even if neither side’s English was perfect. In Korean, I overheard one of the policemen ask a bilingual spectator, who was serving as a kind of volunteer translator, to tell the Venezuelans “that we are doing this not because we want to take away your flags, but because FIFA is telling us that it goes against the rules.” Compared to the FIFA staff, these policemen were sweethearts.

Then again, this is not strange. Months previously, I had seen with my own eyes how many of these young policemen had been bused in from all over the country to donwtown Seoul during the massive protests that forced ex-president Park Geunhye to resign her post and face justice. These policemen had been trained to peacefully and orderly contain protests, to avoid escalation, to tow a calm line. To think that South Korean democracy is three decades younger that the late-puntofijista Venezuelan democracy…

Towards the end of the second half, as the dream of our victorious chamos began to seem distant, our better judgment prevailed. The Venezuelans put away their protest flags, stood around to give a warm, continued, and deserved round of applause to our Venezuela team, second place on the podium but first place in our hearts.

But just as we were heading out of the stadium, it could not be helped: people pulled out their protests flags and, right in the middle of one of the exit corridors of the stadium, a group of about 40 or 50 Venezuelans blocked the way as they repeatedly took pictures in amusement and defiance: You’ve probably seen these pictures on social media. The flag with the silhouette of Maduro within a crossed-out circle, the SOS Venezuela banner, Venezuelan flags turned upside down.

“What does that say?” … “These are the names of the players” … “These are the names of all of us who came to watch the game.”

For quite some time, the Venezuelans were holding off a whole section of the stadium from leaving, but eventually we started walking again.

One comment made me feel surreally like we were walking down la Francisco de Miranda in an anti-government protest. A voice nearby – a battle weary, paranoid veteran from the motherland said, in our Spanish: “chicos, vamos a salir todos juntos por la misma entrada por si nos están esperando para arrestarnos o algo.” It broke my heart.

Of course, nobody was waiting in ambush at the exit to arrest anyone. This was not the motherland; this was a democratic country.

We walked to the bus station and chanted the whole way, celebrating our young heroes who had made it so far, so far away from home. We chanted because we had come to see it all happen, we wanted to show them that they were not alone. And then we chanted some more.

“Y aunque el canto que escuché hablaba de la guerra, de las hazañas heroicas de una generación entera de jóvenes latinoamericanos sacrificados, yo supe que por encima de todo hablaba del valor y de los espejos, del deseo y del placer.

Y ese canto es nuestro amuleto.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate