The Man Who Beat Malaria

On World Malaria Day, we bring you the story of Arnoldo Gabaldón and the epic mid-century war he led against the disease. Has any Venezuelan done more for his country in the last hundred years?

Venezuelans like to dwell on photos of Canaima and Los Roques, but the flip-side of life in this tropical paradise is sharing it with a luxuriant range of diseases. For centuries, disease rendered most of our country practically uninhabitable, and none was worse than malaria, a scourge that made half the country a living hell, until one man decided to do something about it.

His name was Arnoldo Gabaldón —and no, sharing a last name with the Übermensch of Venezuela’s medical world is not easy for a medical student. Every time a new professor reads my name, the question is asked: “Are you related to Arnoldo Gabaldón?”

Malaria made half the country a living hell, until one man decided to do something about it.

Here’s how it is: near the end of the 18th century, back when Simón Bolívar was playing metras, José Gabaldón y Peinado decided to change the Andalusian sun of Málaga for the fog of Trujillo’s mountains. He had a son: José de Jesús Gabaldón Llavaneras who happens to be Arnoldo Gabaldón’s great uncle, and also my own great-great grandfather. I don’t really know what that makes us exactly, but it’s probably in the ballpark of fifth cousin.

My link with el primo Arnoldo may be distant, but his work feels close to me. It should feel close to all of us —we’re short of heroes, and Arnoldo certainly was that.

The kid from Trujillo

A proud andino, Arnoldo Gabaldón Carrillo was born in Trujillo State, on March 1st, 1909. The place is still small today, so you can imagine the tiny provincial outpost it must have been at the dawn of the 20th century. Back then, being the sole child of Joaquín Gabaldón and Virginia Carrillo, both wealthy land owners, guaranteed Arnoldo a comfy childhood and the chance to get along with the politically-engaged provincial elite. His interests soon proved to be different, though. He leveraged his privilege to read books, not scheme for power. From Dante to the Count of Buffon, hundreds of books piled up in his personal library, but one of them marked him for life: Ernst Haeckel’s natural history’s masterpiece, Kunstformen der Natur (Art forms in Nature), a book full of pictures like:

In the detailed, almost fractal illustrations of those strange creatures, Arnoldo found the spark that ignited his interest in biology.

In the detailed, almost fractal illustrations of those strange creatures, Arnoldo found the spark that ignited his interest in biology.

He was a weird kid, the kind that prefers dissecting a fish or a snake while visiting his family hacienda, rather than playing with his dad’s horses.

According to Carmen La Roche’s documentary Arnoldo Gabaldón, la batalla contra la malaria, one of these trips took him to the much-smaller-than-Trujillo town of Monay. Located in central Trujillo, the place named after an eastern French village was little more than a malaria-flooded disease pit.

People don’t realize what Malaria does to you. Imagine the worst flu you ever had: +40°C fever and uncontrollable shivers, repeating again and again in a never ending three to four-day cycle. As long as the fever lasts, you feel completely helpless, too weak to even eat, much less get out of bed.

Until the vector that spreads it is brought under control, you can get it, again and again for years on end, until one day it finally kills you.

Monay was a playground for famished and pale children: jipatos, as they were known, roamed the caserío’s dirt roads. Elders would have looked much worse had there been any, but life expectancy in rural Venezuela back then was short. Arnoldo, less than 10 years old at the time, probably couldn’t process it all, but the image stayed with him for life.

He had met his nemesis for the first time.

Monay was little more than a malaria-flooded disease pit.

Arnoldo graduated from high school at age 15 in 1924, already fluent in English, French and German. His father decided to send him to Caracas, to the prestigious Universidad Central de Venezuela (UCV). Arnoldo takes to the white coat right away, eventually earning a doctorate in medical sciences (1920’s equivalent to modern day med school).

At UCV, Arnoldo realizes Monay isn’t the exception. It’s Venezuela’s “normal”. 600,000 square kilometers were classified as a Malarial Zone, an euphemism for hell on Earth. Even just visiting these places was seen as a death sentence by many caraqueños.

But Arnoldo is not from Caracas.

Along with some of his classmates, he decides to check it out for himself. Going first to Monay and then to several llanero towns, the medical students not only experience the nightmare that small-town Venezuelans faced day after day, but eventually established what would be a fairly well designed research project that identified mosquito Anopheles darlingi as the main culprit of spreading the malaria parasite throughout the region.

As an elite student, he befriends Caracas notables such as Luis Razetti, Enrique Tejera and Rómulo Betancourt, who would eventually drag him into the political realm. Times, just like today, were hard for dissidents back then, La Generación del 28 decided to take a stand against Juan Vicente Gómez 30+ years dictatorship, and although Arnoldo wasn’t exactly giving insurgent speeches at La Pastora during that infamous 1928’s carnival, his defiant attitude and the fact of living with his much more politically-engaged cousin Joaquín Gabaldón Márquez; earned him a short but life-marking stay in jail.

medical students established a research project that identified mosquito Anopheles darlingi as the main culprit of spreading the malaria parasite throughout the region.

According to microbiologist Oswaldo Carmona, during this time Arnoldo swapped Haeckel’s illustrated books for Sun Tzu’s Art of War, inadvertently beginning to build the strategy he would eventually use to fight malaria in rural Venezuela.

He was freed, and graduated in 1930. Arnoldo initially decides to stay in Caracas, repurposing a room in his house to fit his scientific enthusiasm: closets meant for clothes were filled with flasks and test tubes, the nightstand in which a lamp used to be was now occupied by a microscope. It was a very well equipped personal laboratory.

Venezuela was changing, though. The Oil Era was changing the game and opening new possibilities. But the dictatorship was still going, so Arnoldo crosses the Atlantic, ending up in Germany, where he attends the Hamburg’s Tropical Diseases Institute and earns a degree in malariology in 1931. From Hamburg, Arnoldo moves to Rome, where he takes courses bringing him up to date on the most recent advances in the synthesis of antimalarial drugs.

It was impossible to take care of those people, slowly waiting to die without first understanding their relationship with those mosquito-infested water sources.

It was probably during one of his European night walks that he grasps the complexity of the problem awaiting him back home. If Venezuela wanted to take advantage of this new century, it needed strong, healthy citizens, not the jipatos he met in Monay as a kid.

Something had to be done, and he was ready…or so he thought.

After a brief return to Venezuela and an even briefer stay in San Fernando de Apure, Arnoldo crashed into reality. Most part of the knowledge he had gathered in Europe simply couldn’t be applied in rural Venezuela, the unstable tropical weather was to blame: In Italy, Arnoldo witnessed how insecticides, such as Paris green could be applied in the small ponds where mosquitoes carrying the malaria parasite reproduced during summer; the lack of rains during this time of the year made the task incredibly easy. This was not the case in Apure (and the Llanos as a whole) where unpredictable downpours are a year-round norm, transforming the ponds into small lakes. This, added to the fact tropical mosquitoes (unlike those in Europe) can reproduce not only during summer, but during the whole year, rendered the Italian strategy completely inapplicable in Venezuela.

If Venezuela wanted to take advantage of this new century, it needed strong, healthy citizens, not the jipatos he met in Monay as a kid.

Disappointed but still committed to his ideas, he next gets a scholarship from the Rockefeller Foundation to pursue a doctorate in Public Health at Johns Hopkins University Hospital in Baltimore. It’s at this time that he also learns that in order to fight disease, first you have to understand the people blighted by the disease. It was impossible to take care of those people, laying on a bed, scourged by the fever and shivers, slowly waiting to die without first understanding (and changing) their relationship with those mosquito-infested water sources.

He graduates in 1936, just after the dictator Juan Vicente Gómez had died, and makes his final return to Venezuela that same year to marry María Teresa Berti, with whom he would go on to have five children. One of these children is Arnoldo José Gabaldón Berti, who would eventually serve as Minister of Public works (1974-1977) and Minister of Environment (1977-1979).

Arnoldo Gabaldón Berti with his mother, María Teresa Berti.

I called Arnoldo Gabaldón Berti for this story, and he described his father to me as a loving yet strict parent:

He was a really kind father, who loved spending time with his kids, but also a very demanding one. Education was extremely important to him. He always said he didn’t care what we studied as long as we did well at it; in the best institutions and giving the best of ourselves. I remember a story he used to tell us about one of his friends in the ministry, a Spanish physician who came to Venezuela to escape Franco’s dictatorship. My father said that man had lost everything in Spain, yet he’d managed to keep his biggest treasure: the knowledge in his head. They can take everything from you but not what’s in your head; that’s what he repeated us all the time.

Not long after forming his family, Arnoldo was ready to begin with one of the biggest public health care campaigns the world has ever seen.

The war against malaria

War was defined by Aristotle as a mean to obtain peace. Rural Venezuela needed peace and in order to get it, it had to fight against an entrenched enemy: malaria. Some studies suggest it has been with us since we first became humans, affecting even our primate ancestors before us. It’s an insect-borne disease, transmitted, but not caused by mosquitoes from the genus Anopheles, which carry several species of the Plasmodium parasites on their saliva glands. Plasmis, as I like to call them, develop part of their life cycle inside the mosquitoes, but complete it in humans, affecting red blood cells and the liver in the process. Typically, this shows up as some hellish-flu-like symptoms, but that’s just on the surface: malaria screws up your body in all kinds of ways, from anemia and jaundice to bleedings and coma. It is probably the most deadly disease humankind has ever faced, even today it kills about 438,000 people every year, mostly in Africa and South Asia. Seven decades ago, it was like that here.

Rural Venezuela needed peace and in order to get it, it had to fight against an entrenched enemy: malaria.

Since mosquitoes love wet, warm places, malaria has always mauled the intertropical line where we live. It’s not clear if malaria has been present here from pre-columbine times or if it was brought by the Conquistadores and their slaves. It doesn’t matter. For our entire recorded history Malaria has been there, silently killing thousands.

At the time Arnoldo came back from the States in 1936, the Health Minister was Arnoldo’s personal friend, Enrique Tejera. He had grasped that in order to take the full leap into the 20th century, Venezuela needed to overcome the disease. It was impossible to move forward when 60% of the country could kill you at any time — especially considering most of the oil was in that 60%.

To change that, Tejera creates the General Direction of Malariology, naming the 27 year-old Arnoldo Gabaldón as its first director and green lighting him to recruit all the staff he considered necessary to help him in his task.

Malaria is probably the most deadly disease humankind has ever faced, even today it kills about 438,000 people every year.

But stop to consider how unprepared the country was to mount the kind of campaign needed. 35 years of Gómez’s dictatorial isolation had kept the country in amber, the 20th century’s scientific advances stopping cold at the border.

As obsessed as he was with education, Arnoldo decided to change that: the capacity-building campaign he launched was as massive as the field work it was meant to precede. Cooperation agreements were signed with several North American institutions, thousands of books and films were brought into the country and distributed among malariology personnel.

In a matter of months, volunteers from across the nation were trained to become nurses, inspectors and assistants.The direction of malariology managed to take hundreds of uneducated Venezuelans and turn them into specialized health workers. This turned out to be crucial for the eventual success of the program.

Take that, Misiones.

Respected and feared by his footsoldiers, El Director, as Arnoldo was known, was also a beloved boss.

“He wasn’t as ugly as everyone said,” recalls María de Jesús Romero in her own blog. She was one of many malariology visitadoras that collected samples across towns in Cojedes State. “He wore a khaki uniform, knee-high black boots, and a cork-style hat. He’d be barking orders one minute and rolling up his shirt and grabbing a spade or a shovel the next.”

It was this relationship between the workers and the professionals guiding them that made the Malariology Direction one of the most efficient organizations the Venezuelan State has ever created. The way I see it, this was real key to Arnoldo’s success.

After the training was done, Gabaldón and his foot soldiers were dispatched to the battlefield.

In a 1973 interview with Sofía Ímber and Carlos Rangel, Arnoldo described some of what they found out there. It’s staggering.

Abandoned houses and conucos, left behind, animals included, throughout empty towns, a crying baby trying to feed from the breast of her dead mother, or corpses rotting inside houses as the living relatives were just too weak to bury them.

“Abandon all hope ye who enter here”- with the inscription read at the gates of Hell in Dante’s Inferno, Arnoldo summarized his own experience in the field.

Early on, inspectors and visitadoras gathered blood samples taken from the earlobes of infected patients and collected mosquitoes feeding on the pack-donkeys out in the field and studied larvae found in small ponds. At the same time, local women, nicknamed quininizadoras delivered free, state-sponsored quinine —the best available antimalarial drug at the time.

“My work consisted in this,” María explains, describing her role as visitadora. “I was given a small box with a pen in it, you could detach a tiny piece from it and you got a sharp point that could be disinfected and used to pierce an earlobe and get a drop of blood. This drop was then put on a crystal slide (…), taken to the lab and soaked in methylene blue (…), an entomologist would then check it on the microscope and conclude if the patient did or did not have malaria.”

“My work consisted in this,” María explains, describing her role as visitadora. “I was given a small box with a pen in it, you could detach a tiny piece from it and you got a sharp point that could be disinfected and used to pierce an earlobe and get a drop of blood. This drop was then put on a crystal slide (…), taken to the lab and soaked in methylene blue (…), an entomologist would then check it on the microscope and conclude if the patient did or did not have malaria.”

It was this slow, steady epidemiological work that got real results: After 100,000 water samples were taken from ponds, half a million larvae were observed and, 8,000 blood samples taken from kids; Arnoldo’s team concluded the Llanos were the worst affected region in the country and that action should be focused on rivers and swamps.

Gradually, Arnoldo realized that every five years, malaria cases would skyrocket. This regular, five-year schedule seemed to map onto the mosquitos’ reproductive cycle. This insight was eventually used to plan a policy of larvicide use and drain of small ponds and water sources surrounding towns all around the country.

Arnoldo’s brother-in-law played a key role in this process, as the head of the Directorate’s Antimalarial Engineering branch (yes, antimalarial engineering is actually a thing) Arturo Luis Berti fought mosquitoes with math and physics: epidemiological research proved that Anopheles darlingi and albimanus, two of the most common vectors in eastern Venezuela could only lay their eggs in stagnant water — that may seem obvious to you and me, but somebody had to discover it, you dig?

Under Berti’s leadership, aqueducts and pumping stations were built by the Direction in collaboration with US universities (and with funding from the Rockefeller Institute) to keep the water running in places such as Maracay, Puerto Cabello and several others relatively big towns located in at-risk areas. Similar projects were developed all over the Malarial Zone, bringing piped drinking water to rural towns, making them much less dependant on natural sources that were at much higher risk of larvae.

Abandoned houses and conucos, left behind, animals included, throughout empty towns, a crying baby trying to feed from the breast of her dead mother, or corpses rotting inside houses as the living relatives were just too weak to bury them.

The process was effective, but slow and expensive. Government first, and public opinion later, started to roll their eyes to the bunch of scientists and doctors spending huge amounts of public money on mosquito-hunting trips while kids all over the country kept dying.

After an epidemic outbreak that lasted from 1940 to 1942, pressure for tangible results intensified, and for the first time, Arnoldo acknowledged he was feeling the pressure.

“They left me that directorate with an attitude like ‘there you go doc. If you fail, it’s you and your team’s failure’.” said Gabaldón about this time in an interview some years later.

Almost eight years after he was named to lead the malariology directorate, a miracle came straight from the north.

It was 1944 and the United States was at war on two fronts. The German defenses were collapsing, but the Pacific was a completely different story. American soldiers had to deal not only with Japanese troops, but also with the whole stew of tropical diseases in the South Pacific. The Army asked Dr. Arnoldo for some help. It was in the United States, while instructing American privates on how to mitigate the effect of some of these diseases that he learned about the usage of an old, recently re-discovered insecticide by the US Army Medical Corps: dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, DDT to you and me.

DDT wasn’t like the other bug-killers around back then. It didn’t evaporate after it was sprayed on walls, so its effects lasted much longer, making it both more effective and cheaper. Decades later, scientists would figure out this stuff was pretty bad for the environment, and DDT would become highly controversial. But in Venezuela in 1944, it was the game-changer Arnoldo was praying for.

After his return to Venezuela, and a couple of phone calls from president Medina Angarita, DDT imports, fueled by the strong oil industry, got going in earnest.

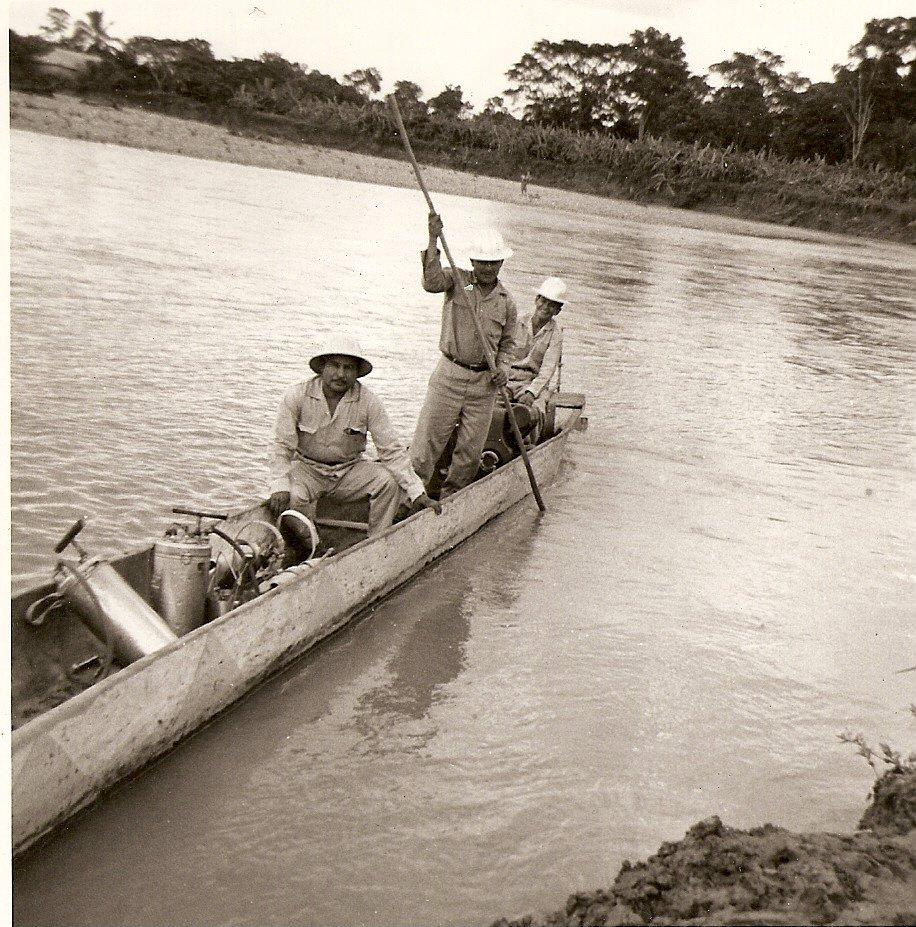

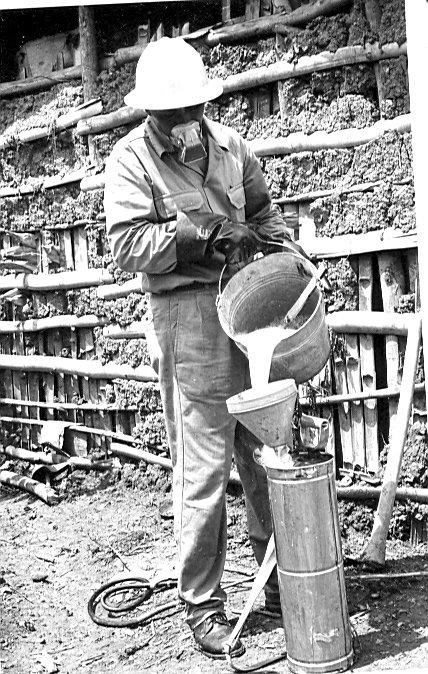

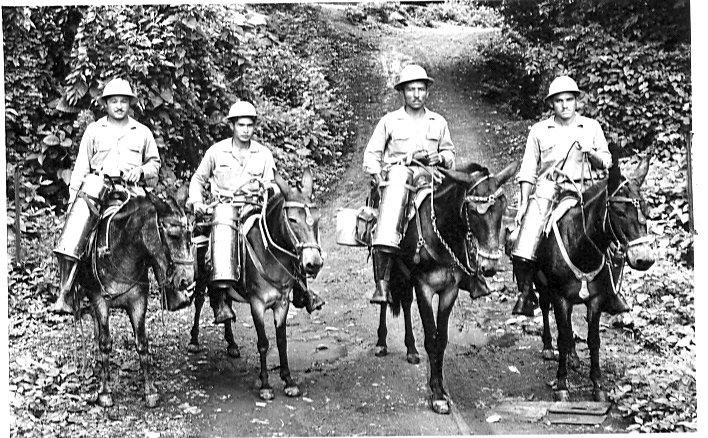

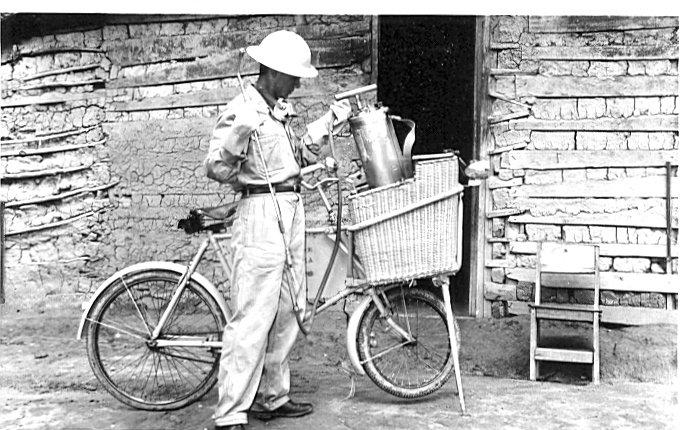

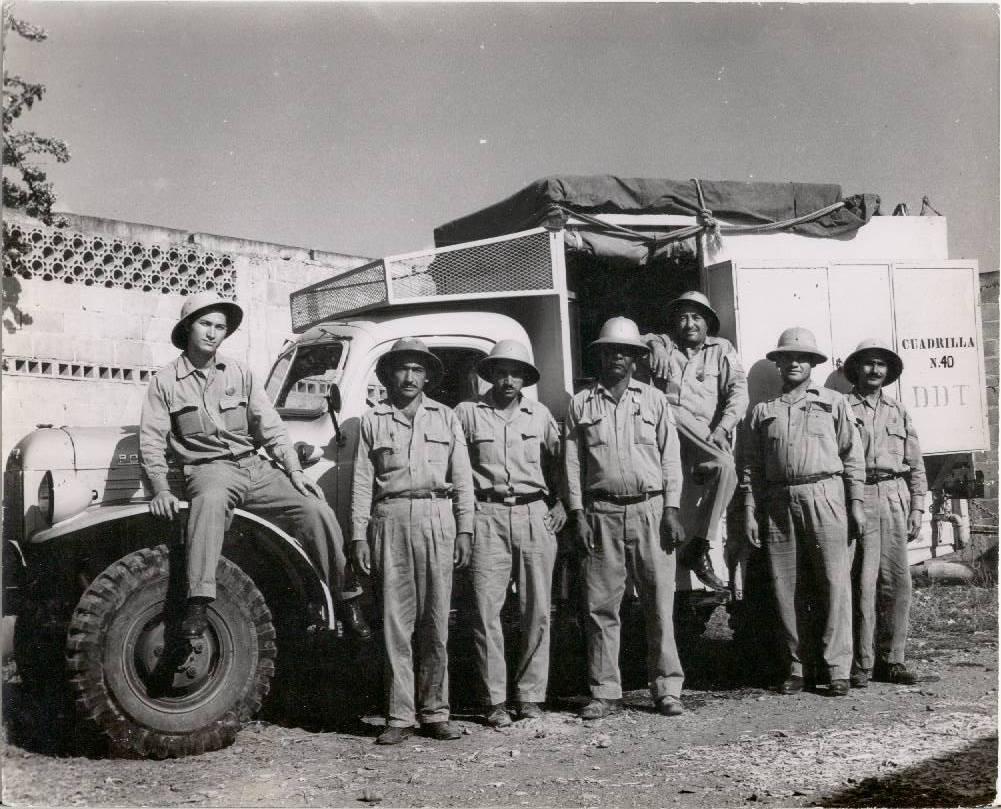

Arnoldo assembled a well-oiled team of fumigation squads. Each squad was formed by a variable number of workers who were dispatched all over the Malarial Zone. Going house by house; the squads flooded countless Venezuelan towns with DDT; moving by ground, sea and air, using everything from jeeps and boats to horses and mules to reach the most isolated corners of the country.

These guys were rural Venezuela’s finest. Wearing nice hats, pants and boots given by the Directorate and riding the best mules to be found, fumigators worked around the clock under the relentless Llanos’ sun, carrying their heavy pumps on their backs and spraying over 280 square meters of ranchos’ walls per hour with DDT, every three months, beating even their North American colleagues’ standards.

These guys were rural Venezuela’s finest. Wearing nice hats, pants and boots given by the Directorate and riding the best mules to be found, fumigators worked around the clock under the relentless Llanos’ sun, carrying their heavy pumps on their backs and spraying over 280 square meters of ranchos’ walls per hour with DDT, every three months, beating even their North American colleagues’ standards.

They made the difference. They’re the ones who should appear on banknotes.

The campaign was a stunning success. Before the campaign was launched, 112 people per 100,000 were dying of Malaria in the affected zones: to give you a sense of scale, that’s nearly twice the number dying from urban violence today. Then the campaign was launched — on December 2, 1945 in Morón, Carabobo State, to be precise— and five years later malaria national mortality rate had plummeted to 9 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants.

By 1955 it had decreased further still to just 1 per 100,000 inhabitants, and the disease had been completely eradicated in more than 300,000 square kilometers. In 1961 World Health Organization (WHO) declared Venezuela had effectively eradicated malaria from 68% of the Malarial Zone (over 400.000 square kilometers) being the first country to achieve such a great extension, and ten years later the success reached an astonishing 77% of the zone.

Contrary to what you sometimes hear, malaria was never really wiped out from all of the territory, but it was reduced to isolated, mostly uninhabited areas where transmission dynamics made DDT spraying inefficient, that’s why malaria cases were reduced to almost zero during the late 50’s.

Some historians say Venezuelan history could be divided in pre and post DDT years.

A legacy for the future

It had been done. Arnoldo Gabaldón and his team managed to overcome one of the greatest social problems Venezuela had ever faced. As people stopped dying in the interior, a demographic explosion took place and the country started running for real: Population grew from about 4.3 million in 1945 to 7 million in 1960. Demographic transition doesn’t “just happen”: it’s made to happen when mortality rates fall and women start having fewer children as a result. My cousin Arnoldo did that!

Contrary to what you sometimes hear, malaria was never really wiped out from all of the territory, but it was reduced to isolated, uninhabited areas.

Yes, the development of cities ended up fueling Venezuela’s transition into an urban society during the 60’s, but that development would have been impossible with mosquitoes killing everyone around Acarigua, San Juan de los Morros or Maturin to name a few cities that once belonged to the Malarial Zone. As Tejera had foreseen, the 20th century had finally arrived and the people could enjoy it whether they lived in Caracas or in Ortiz. Jipatos were past history.

The Malariology Directorate did much more than just eradicate malaria, they had given this country a future. Arturo Uslar Pietri, said it himself: “the social and political changes the country is undergoing are not just the consequence of a Venezuela with oil, but also of a Venezuela without malaria.”

To put things in perspective, the disappearance of malaria meant that the habitable area of the country doubled. As Arnoldo said in his book Política Sanitaria, countries usually go to war expecting to take some small land away from their neighbors, generally about 10% of what they already had. This war, on the contrary, earned Venezuela an increase of over 100% in its exploitable territory, the equivalent of conquering a country the size of Germany.

With Marcos Pérez Jiménez

Venezuela was not the only country to defeat malaria at this time: countries such as Brazil, Italy, Spain or Greece started showing promising results. Malaria’s days as a scourge for mankind seemed counted.

Countries usually go to war expecting to take some small land away from their neighbors, generally about 10% of what they already had. This war earned Venezuela an increase of over 100% in its exploitable territory.

Arnoldo spearheaded this process, though, and Venezuela became known for it. Thousands of foreign physicians from places like India and China came to Maracay, where the Directorate’s HQ was located, to learn the “Venezuelan way”. In 1944, even before the astonishing success of the DDT campaign, Brazil and Venezuela were already seen as the reference cases for malaria studies in the Western hemisphere.

Yes, there was a time we were famous for being good at something, the best, actually.

At this point Malaria wasn’t only a job, but much to his wife’s dismay; a central point in Arnoldo’s life. Here’s how his son Arnoldo Gabaldón Berti remembers it “My father didn’t keep work out of the house, it was a part of him. Whether we were at a family gathering or spending time with friends, malaria always came up. My mom used to complain, but eventually she also ended talking about it,” his son remembers.

Following the success against Malaria, in 1959, Arnoldo is named Health Minister by his long-time friend, Rómulo Betancourt. For five years, Gabaldón led the place applying the same principles used to fight malaria: extensive capacity-building and intense field work.

“He was an extremely pragmatic man”, Gabaldón Berti tells me.” When he became Minister, child mortality was a real problem. Newborns died around the country because there was not enough trained personnel to help with childbirth. My father thought that training doctors and sending them throughout the country to take care of the problem would take too long and cost too much, so he decided to create a midwifery program. The Health Ministry would teach local volunteers basic strategies to prevent infection and other life-threatening problems in babies and their mothers. The strategy was an astonishing success and comadronas would proudly show diplomas signed by him whenever a doctor tried to take their place during labor.”

“This was the key for his success, both in malariology and in the Ministry” he remarks.

Gabaldón Berti and his father, Dr. Arnaldo Gabaldón, in a Miraflores reception c.1975.

His focus on preventative medicine paid off, increasing life expectancy from 59 years in 1960 to 62 years in 1965. This was 40 years before Barrio Adentro tried (and failed) to do the same.

Arnoldo’s era at the Health Ministry were also the glory years of public health research in Venezuela. Three new species of Anopheles were discovered by Venezuelan entomologists, over 77 research projects took place in the Venezuelan fields. Hand-in-hand with North American institutions, Venezuelan science jumped into the future. Arnoldo Gabaldón also worked as a professor, teaching first at his alma mater: UCV and later at Cambridge University, being the first Simón Bolívar Professor of the Latin American studies centre at the British university.

Gabaldón became one of the world authorities when it came to fighting infectious diseases, and as such, was appointed by WHO as a consultant expert, advising the organization’s work against malaria in the five continents.

Arnoldo Gabaldón Berti, with his son, and his a portrait of his father, Dr. Arnoldo Gabaldón, in the National Academy of Physical and Natural Sciences, 2006.

But success had taken its toll, too, as Ana Teresa Gutiérrez explains in her book, Tiempos de Guerra y Paz: Arnoldo Gabaldón y la investigación sobre la malaria en Venezuela (1936-1990):

The fact that malaria started to be seen as an eradicable disease made people complacent. As soon as the incidence plummeted, health authorities both here and in the rest of the world lost interest in the disease.

Field research was almost completely halted in the 70s and only DDT fumigation remained operative. Physicians only cared about the malaria case, not its context, the disease but not those blighted by it. And since cases were increasingly rare, investment dried up.

“The research effort we’d carried out started to decay,” Gabaldón said, years later as Gutiérrez writes in her book, “simply because we were so successful people believed there was nothing more to be done.”

It didn’t happen in Venezuela alone, but unlike us, most part of the world saw the mistake soon enough.

Slowly but steadily, cases reappeared, in growing numbers every year. Some epidemic outbreaks in the 70s were brought under control but our luck would eventually run out.

The fact that malaria started to be seen as an eradicable disease made people complacent. As soon as the incidence plummeted, health authorities both here and in the rest of the world lost interest in the disease.

Underinvestment, voluntary at first, then imposed by an increasingly hostile economic environment caused the disaster of 1990: 46,910 reported cases that year. The government got scared, after improvised emergency measures were taken, cases dropped to about 12,000 the following year. The damage, however, was done. Decades of echarnos las bolas al hombro came back to bite us in the ass.

Another outbreak hit on 2004, it was chavismo’s first encounter with a long forgotten problem: more than 45,000 reported cases that year. This time we had a strong oil barrel, so we should have been able to respond. But we didn’t, Hugo Chávez was too busy spending the petrodollars on misiones to care about such a cuarta república problem as malaria.

Who cares about financing a bunch of lab nerds looking for larvae when you have a Mercal to build, right?

As a matter of fact, one of the first moves Chavez’s reorganized Health Ministry decided to take at the dawn of the 21st century was to dissolve Malariology Directorate, ignoring the recommendations of well… pretty much everyone, including several chavista physicians.

The results so far, are shocking:

Of the 390,000 cases officially reported in the whole of Latin America and the Caribbean in 2014 (the last year that we sent official data to WHO), the plurality (37%) came from Venezuela. That same year, Venezuelan health minister assured WHO that 100% of it at-risk population had been protected with indoor residual spraying, even though we also happened to be the second lowest country in investment for malaria control per-person-at-risk, with an astonishing expense of 50 U.S. cents for each person at risk. Paraguay, for context, invested about $20 per person at risk that same year. You can read the full WHO report here.

One of the first moves Chavez’s reorganized Health Ministry decided to take at the dawn of the 21st century was to dissolve Malariology Directorate.

The situation today seems extremely worse. No official data has been released in almost two years, but extra-official reports talk about more than 148,000 cases until september 2016. Absence of medicines required to properly treat the patients, the complete lack of public policies, recently worsened by the dramatic economic collapse of the nation and the extensive illegal mining in endemic areas have all managed to destroy Arnoldo Gabaldón’s lifelong work.

Even Monay, the small Trujillo town where it all started seems lost today. Although Arnoldo’s work proved effective ending malaria, new scourges took its place: from organized crime to slaughtered miners, life in the place is still a living hell.

All that’s left of Arnoldo’s legacy is his name, always in my teachers’ memory and given to the renamed Escuela de Malariología, nowadays, an academically-flawed, government-run institution standing at the original Malariology Directorate building in Maracay.

El primo Arnoldo died on september 1st, 1990. Three years before I was born. I wish I’d had the chance to meet him. But I’m also glad he didn’t live long enough to see his legacy completely decimated.

Dr. Gabaldón with his wife, María Teresa Berti, his son, Arnoldo Gabaldón Berti, and siblings, 1989.

“I don’t know what my father would say if he saw what this country became,” his son, Gabaldón Berti, tells me. “I don’t think anyone could have ever imagined the degree of regression Venezuela is facing. It’s a complex problem and it’ll take a lot of time to fix it. I’m not only talking about the malaria resurgence, but also the current state of democracy. He had a really strong democratic vocation… He always felt honored of living the first years of Venezuelan Democracy alongside with Betancourt (…) If he was alive, I bet that’d be his first advice: to bring our democracy back.”

Today, as we mark World Malaria Day, all I can say is thank you, Arnoldo. Thanks to you and to your whole crew, wherever they may be; not only for laying down the groundwork for a new country that is hopefully yet to come, but also for proving us that as you used to say, el venezolano es un individuo que cuando quiere, se empeña.

Y nos vamos a empeñar.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate