Good and Bad Reasons to Hate Francisco Rodríguez

No Venezuelan economist comes close to stirring the passions FRod does. We work through the reasons why, teasing out the silly from the serious, and the merely serious from the absolutely unacceptable.

Last week, the opposition WhatsApp rumor mill exploded with false rumors about Francisco Rodríguez, the controversial Chief Economist for Torino Capital. All week, anonymous attacks against him ricocheted around influential Caracas phones at warp speed: Francisco was at Hotel Cayena cooking up some crooked deal between the government and the opposition, or to line the pocket of this or that bolichico, or God-only-knows what else.

We actually spent some time trying to verify the rumors, and it was like chasing smoke: third-hand stories of outlandish conspiracies that people swore up and down were definitely true, except there was not a bit of evidence to back them. “Me contaron que una persona que estuvo dijo que,” kind of stuff. Garbage.

I spoke to three separate sources who were at the Cayena pow-wow, and they uniformly rolled their eyes at the stories, describing instead a relatively standard investor trip of the kind investment banks put together up and down the hemisphere all the time: Q&A sessions with analysts and policy-makers, drinks with sources. The usual.

Serious, level-headed opositores are ready to believe, well, more or less any story anyone is willing to peddle about him.

That such far-out conspiracy theories get widely shared —and that they get widely believed— is one indication of how unusual Francisco’s position has become. Not to put too fine a point on it: people hate him. He’s intensely distrusted by a wide range of people in the opposition. Serious, level-headed opositores are ready to believe, well, more or less any story anyone is willing to peddle about him.

I always find this a little bit jarring because, well, Francisco Rodríguez is my friend.

I say that with some trepidation; I know how people react. Their body language shifts, the way yours might if you found out an old friend is into Scientology. I can just about see the little gears turning in their heads as I get reassigned to the “not-entirely-trustworthy” category.

And it’s had real consequences for me, too. Some people straight-up refuse to write for Caracas Chronicles because they know I’m friendly with him. It’s that intense.

But Francisco is my friend, and not in the bullshit, paper-thin way journalists and politicians sometimes call each other friends. He’s someone I ask for personal advice. I’ve stayed over at his apartment in New York. And I make no apologies for it, not just because Francisco has a reasonable claim to the title of “smartest person I’ve ever met,” but because, in person, he turns out to be kind of a mensch: warm and hospitable, generous with his time, funny, and continually in possession of some outrageously good booze. Put him together with Maria Eugenia, his enormously charming wife, and it’s not easy to find better company.

So it’s always a bit jarring for me to see how intensely people despise him, though it’s not necessarily that surprising. FRod offers a unique combination of personal and political traits more or less optimized to make a certain breed of opositor deeply uncomfortable: he’s a fiercely smart, unrepentantly ambitious, enormously cerebral leftist with a huge appetite for risk-taking who has a contrarian streak as big as the Ritz and an ego to match.

The key to grasping his worldview is certainly that contrarian streak. FRod never saw a cosy consensus he wasn’t minded to challenge. Profoundly allergic to groupthink, the guy finds deep fulfillment in swimming against the intellectual tide. The more you think a given economic fact is obvious, the more Francisco needs to take it out and probe it for weaknesses. It’s a mindset that’s made his clients a lot of money over the years, but hasn’t made him a lot of friends. I don’t think that bothers him one bit.

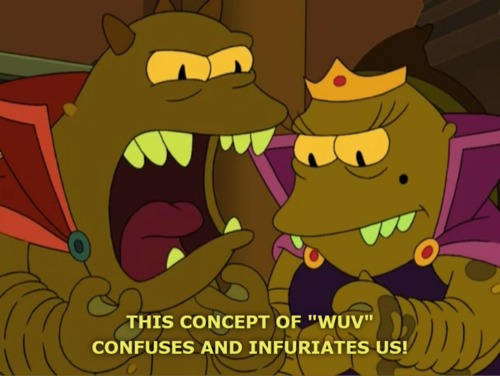

That comfort with standing alone probably accounts for a good deal of the passions he arouses. In the end, he always reminds me of that clip from Futurama when Emperor Lrrr of Omicron Persei 8 is handed a Valentine’s candy that says “I wuv you” and just flips out:

I think FRod is up against something similar: “this concept of a hardcore leftist who is also a genius Wall St. economist confuses and infuriates us!” the WhatsApp-roots rage. I get that.

I think FRod is up against something similar: “this concept of a hardcore leftist who is also a genius Wall St. economist confuses and infuriates us!” the WhatsApp-roots rage. I get that.

But just because Francisco is widely loathed for silly reasons doesn’t mean there aren’t some good reasons to question him, too. And just because he’s my friend doesn’t mean he gets a free pass. So let’s do a bit of probing of our own, starting with:

The Credibility Issue

The sophisticated alternative to the knee-jerk school of FRod hate centers on the peculiar role he’s come to play in the Venezuelan public sphere. At Torino Capital, Francisco is the Chief Economist of a Wall Street broker-dealer that’s heavily specialized in Venezuela and PDVSA bonds. He can’t really claim to be a disinterested observer of the Venezuelan financial scene.

Thing is, he kind of does.

A Chief Economist’s job description is straightforward: to describe the world as it is and as it is likely to be. And nobody disputes Francisco is good at this kind of positive analysis: back in 2014 and 2015, when Credit Default Swap markets were giving an overwhelming probability of default to Venezuelan debt in 2016, Francisco bucked the trend, telling clients Venezuela would pay. He was way out on his lonesome on that call, and he got it right.

The problem is, Francisco doesn’t limit himself to positive analysis: he has, over the years, continually dipped his toes into the world of normative analysis, too. In public fora, again and again, he’s gone beyond saying Venezuela can pay and will pay to saying Venezuela should pay. That paying is in Venezuela’s best interest.

Trading Venezuela debt is Torino’s bread and butter.

And he hasn’t made that case once or twice. He’s made it again and again, in Venezuela and abroad. On Bocaranda and on Globovision and on Bloomberg View and at the Brookings Institution and at AS/COA. (I should know, I moderated that last panel.)

And advocacy of this type is…problematic.

Why? It’s not that Francisco owns the bonds whose payment he’s counselling: he doesn’t. It’s that trading Venezuela debt is Torino’s bread and butter. His firm’s business model relies on the commission clients pay when they buy and sell the bonds that he then earnestly advises Venezuelan policy-makers should be paid.

Multiple sources I consulted for this post told me that, in the event of default, Torino’s business would likely dry up. It’s possible the firm would face some near-term upside from default —there’d likely be one last big wave of trades as existing institutional investors unloaded their holdings to vulture fonds— but, on the whole, it’s hard to imagine that windfall would make up for the death of the goose that lays the golden eggs.

What Francisco wants us to believe is that, by some odd coincidence, his clients’ interest match ours. By a fortuitous confluence, the policy that’s in the best interest of Venezuelans also happens to be the one that our creditors favor, which by an amazing stroke of luck happens to coincide with the policy that would keep his firm’s business going.

This isn’t, to be sure, impossible —hell, Francisco makes a pretty good argument that it is indeed the case. But it isn’t the consensus view. Not even on Wall Street.

Some people see this situation and smell a conflict of interest. I talked to three separate lawyers for this story, and I’m convinced that’s not the right way to look at it. A conflict of interest arises when one person has a legal duty to act as an agent to two different principals. That’s not the situation Francisco faces, because he has a legal duty to just one party: Torino’s clients.

So we come back to the question of credibility. From the point of view of the debtor (i.e., the Venezuelan people), taking advice from someone who has a legal duty to answer to your creditors is…well, let’s just say it may not be the smartest thing you could do.

“Look, yes, my institutional position is one of the things people should take into consideration when they assess my policy views,” is how he put it.

It’s not so much that FRod is doing something wrong in offering his view, it’s that the Venezuelan public probably has powerful reasons for taking that view with a pinch of salt. (Or, depending on who you listen to, a truckload of salt.)

I put this view to Francisco, and he pretty much conceded the point.

“Look, yes, my institutional position is one of the things people should take into consideration when they assess my policy views,” is how he put it, hurrying to add that it should be weighed against other factors, like the quality of the analysis itself. After all, he says, if all you care about is getting your analysis from a senior economist unsoiled by contact with Wall Street, you might as well get your policy views from Jorge Giordani.

Fair enough.

How heavily you choose to discount Francisco’s policy stances due to his professional commitments is, of course, up to you. For plenty of FRod-haters, it’s all the reason you need to discount every last word that comes out of his mouth. I think that’s throwing the baby out with the bathwater.

For one thing, because the conflicts I really worry about are the ones that aren’t disclosed, and Francisco’s position couldn’t be any more disclosed: the guy is always introduced as Torino Capital’s Chief Economist. Short of tattooing “I represent bondholders” across his forehead, it’s hard to see how much more spelled out it could be.

But the bigger reason behind my skepticism is that the strength of feeling that attaches to FRod-bashing seems to me out of all proportion to the alleged misdeed. Indeed, other Venezuelan economists on Wall St. who take stances closer to the opposition-consensus view and also take part in the public sphere don’t get anything like the level of pushback Francisco gets (cough-cough-grisanti-cough).

The point is broader, though: in a public sphere brimming with economists who have a ministerial sparkle in their eyes as well as a dazzling variety of interests that are rarely if ever disclosed, it feels unfair to me to go after the one guy who levels with us about where he’s coming from.

Ultimately, I can’t shake the feeling that the pearl-clutching over his ethical conflict gets the causality backwards: it’s not that Francisco is saying Venezuela should pay bondholders because he works for bondholders, it’s that he works for bondholders because he thinks Venezuela should pay them.

A firm like Torino was always going to recruit a Chief Economist from the ranks of economists who are genuinely convinced Venezuela should pay.

It’s a messy old world we live in, and I for one am not really comfortable crucifying Francisco for getting a cush job working for people who recruited him because they agree with him.

But the other reason I don’t get all that worked up about this is that I see it as a red herring. It’s not really Francisco’s ethical conflict people hate. The pass other economists get in a similar position proves it.

No, lurking just beneath the surface is a whole other set of reasons people hate FRod: substantive reasons, political reasons and, to my mind good reasons. Reasons that keep me up at night asking myself if it can really be ok to be friends with this man. Reasons that strike me as a million times more damaging than some half-baked story about a supposed conflict of interest that is A-disclosed and B-not even a real conflict of interest to begin with.

And those reasons, to my mind, all stem from:

The UNASUR Job

In May, 2016, just after quitting his job at Bank of America, and just before joining Torino, Francisco Rodríguez took a peculiar ‘working holiday’. For two months, he led an international team of economists put together by UNASUR (the chavista “Union of South American Nations”) to advise the Venezuelan Regime on economic policy.

From May through June of 2016, Francisco worked side-by-side with such luminaries as Mark Weisbrot to advise characters like then-minister and economics VP Miguel Pérez Abad, alleged teen-rapist (and demonstrated bolivar-rapist) Nelson Merentes and the semi-legendary Rodolfo Medina on a package of reforms to pull the Venezuelan economy out of its tailspin.

The team eventually presented a reform plan to Pérez Abad on June 10th, though the resulting document was never made public (the government didn’t agree to that.) Francisco was slated to meet Maduro himself to present it the next day, June 11, but the meeting never happened: Francisco went to Miraflores, but Maduro left him waiting. The cabinet never voted on the reform proposal.

A defeated Francisco schlepped back to New York and took up his post at Torino on July 9th.

His “My Summer Vacation” essay for 2016 might as well have been titled: “How I tried to save the Bolivarian Socialism from itself.”

Now, I don’t know exactly what was in this proposal, but having followed his career over the years I can hazard a pretty good guess: ending the multi-tier exchange rate regime and unifying the FX system will have been central to it, alongside some of the other basic reforms needed to re-establish something like a working price system and wringing out the worst of the distortions that were pushing the economy into depression.

Francisco, in other words, spent two months working full time to try to stabilize Venezuela’s dictatorship economically just enough to remain politically viable. His “My Summer Vacation” essay for 2016 might as well have been titled: “How I tried to save the Bolivarian Socialism from itself.”

The problem here not is not that Francisco is a chavista. He isn’t. The guy has an Economics Ph.D from Harvard and a nuanced understanding of the need for markets if societies are to operate at all. But his politics are pretty far to the left, and he doesn’t seem to me to be immune to the damaging fantasy that, given minimally competent economic stewardship, the revolution could be redeemed. And worse, that he’s just the person to redeem it.

For my money, this is sooooo much worse than anything else the guy is alleged to have done it’s hard for me to figure out why people even spend time talking about the other stuff.

Let’s spell this out in detail:

Towards the middle of last year, Francisco Rodríguez looked Diosdado Cabello up and down, looked Tareck El Aissami and Nelson Reverol up and down, looked people like Maikel Moreno and Luisa Ortega Diaz and Francisco Rangel Gómez up and down and thought to himself “let’s play ball!” Francisco took an economic rescue mission to people who’ve stolen hundreds of billions of dollars and trafficked hundreds of tons of coke, people who’ve jailed thousands of political dissidents and destroyed Venezuela’s democracy, people who’ve jailed my friends, people who’ve forced me and my family into exile, people who’ve destroyed the hopes and aspirations of a whole generation of Venezuelans and turned our country into a goddamn dystopian nightmare. He looked them up and down, took in their yachts and their blood-soaked hands, their surgically enhanced teenage mistresses and their utter contempt for Venezuela, and thought “you know what, I’m comfortable working to stabilize the economy in ways that’ll make it easier for these people to stay in power.”

Fuck that guy. Seriously. fuck. that. guy.

Look, if you’ve read this far, you know I’m obviously minded to give FRod the benefit of the doubt. And I tried, I really did. Trust me, I tried all the rationalizations.

I tried thinking that, as it turned out, the regime stabilized itself even without his reform proposal, so in the end we wound up with the same dictatorship, only built on top of a much deeper layer of misery.

I tried telling myself that regular Venezuelans do not and did not deserve the hardship the regime’s catastrophic economic policies have forced upon them, that it took courage to say “people need relief now, and while maybe I can’t do anything to overthrow the regime I can do something to lessen the deadly human cost its cluelessness has imposed.”

I tried telling myself that, as an economist, Francisco is subject to something like the Taxi cab rank rule British lawyers face: in principle, he should be willing to dispense expert advice to anyone who seeks it it without regard to their political ties.

I even tried contorting myself into the counterfactual pretzel it takes to think that if the government had accepted his advice and the economy today was less awful, Maduro would’ve faced fewer pressures to turn virulently autocratic and maybe Venezuela could have preserved more democratic features than it has.

But the smell of bullshit hangs heavy over all of these narratives.

It was a monstrous conceit from day one.

The reality, I think, is simpler. It is possible, in the end, to be too smart for your own good: too persuasive, so persuasive you manage to mojonearte a ti mismo, to bullshit yourself into believing helping Nicolás Maduro stay in power is a good idea somehow.

And my sense is that this is what happened to Francisco on the UNASUR file: he persuaded himself that he had some sort of special power able to overcome the hard, criminal core of the chavista regime. That he, and only he, could redeem the chavista experiment for the left somehow.

It was a monstrous conceit from day one: a gambit born of an out-of-control ego bordering on the ridiculous in its overestimation of its own powers.

No, Francisco, coño, you were not going to fix chavismo, what were you thinking!?

The UNASUR mission was FRod at his most dangerous and worst. It created an atmosphere where his later closeness with Henri Falcón couldn’t help but throw shade on the governor, seeming to confirm everyone’s suspicions about both of their allegiances. It was UNASUR that created the conditions for last week’s WhatsApp bullshit tsunami to be believed. It’s a bed he made, and now he has to lie in it.

And the UNASUR episode left even those of us who want to sympathize with him in an impossible position. If someone walks up to me today and says “that guy tried to help the dictatorship stay in power, we can never trust him again,” I got nothing. Just nothing. There’s nothing I can say to that person.

Does that mean I don’t consider him my friend anymore?

Not at all. I still do.

It’s just that sometimes your friends scare you, and Francisco very definitely scares me sometimes. There’s a messianic streak there, a deep-down, to-the-bone conviction that his name will end up inscribed in Venezuela’s history books that I find alternatively intoxicating, silly, terrifying, and inspiring.

I don’t have any other friends like that. It’s enormously compelling.

And dangerous, too. Enormously dangerous.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate