The Zucaritas Principle [Updated]

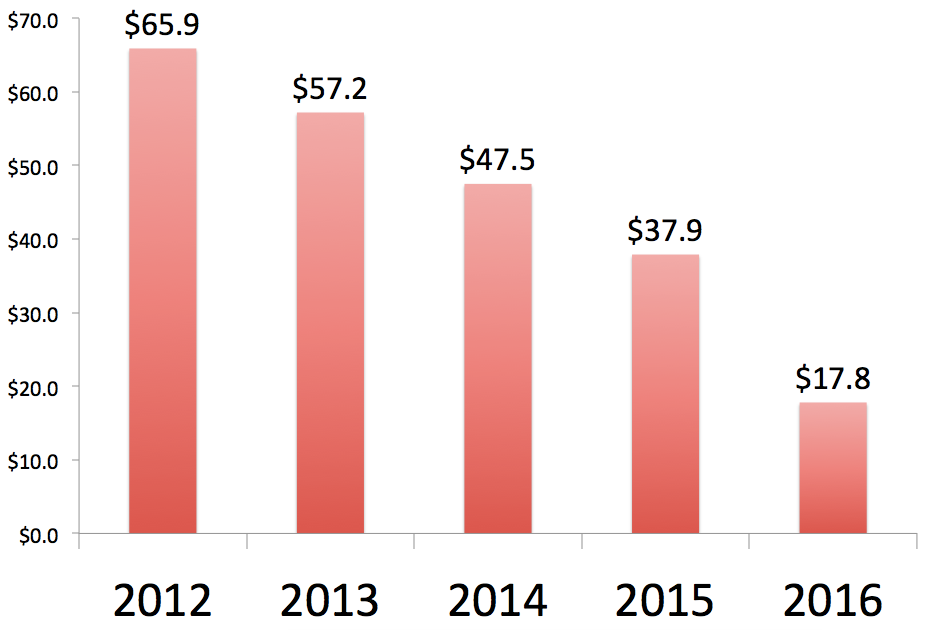

Nicolás Maduro just announced imports fell to a shocking $17.8 billion last year, down 73% in four years.

Speaking to business groups yesterday, Nicolás Maduro announced that total imports last year had collapsed to a shocking, barely survivable $17.8 billion: a shocking 73% fall from their peak during the Bonanza Years just four years ago. The chart should give you shudders.

Imports, in billions of US dollars

This is bad. How bad? Early last year, when he was being very, very pessimistic, our Pedro Rosas hypothesized imports for 2016 could fall as low as $27-30 billion. He worried at that level, people would surely go hungry.

Late last month, Pedro revisited the issue and noted imports were likely to close the year nearer $20 billon: way, way worse than what he’d thought would be apocalypse back in February.

Last night, he announced a shocking — in a sense, unbelievable — figure of $17.8 billion for 2016.

[Update: There’s some question about what that means. Since the figure is quoted from a typical, rambling Maduro speech rather than a formal publication it’s possible that, for instance, PDVSA’s imports are not included in this figure. If that’s the case, the global figure would be closer to $23 billion.]

The dollars they needed for some key bit of the process weren’t around…and some unfortunate sap in the marketing department got stuck having to put ecological lipstick on that macroeconomic pig.

Either way, these import levels. First there’s the obvious fact that we produce much less food than we once did and if you don’t have money to import you can’t bring in enough food for everyone to eat. That’s clear enough. But the other reason this is horrible news is a little bit less intuitive, and takes some explaining.

Think of it as the Zucaritas Principle.

Early last year, Kellogg’s caused some waves by unveiling the ridiculous “ecological” Frosted Flakes box above, with a sad, colorless Tony looking distinctly less than grrrrrrrrreat.

It’s easy enough to figure out what happened there: amid the almighty imports crunch, Kellogg’s couldn’t import the stuff it needed to produce the traditional, colorful Zucaritas boxes we all remember from childhood. Maybe they couldn’t get the dollars to bring in the right kinds of ink, or some industrial precursor to them, or the right kind of cardboard…who knows? The dollars they needed for some key bit of the process weren’t around…and some unfortunate sap in the marketing department got stuck having to put ecological lipstick on that macroeconomic pig.

The kind of predicament Kellogg’s faced is a pretty general feature of the Venezuelan economy. It’s not quite true to say we don’t have an industrial sector, we do! It’s just that that sector is deeply enmeshed in globalized supply chains. There are very, very few products where the entire supply chain is fully internal to Venezuela (rum, maybe?) For the most part, Venezuelan industry is in the same predicament Kellogg’s found itself in: it has a few links on the supply chain and depends on foreign suppliers for others.

The supplies, the inputs, the materials and spare parts and machines and tools it takes to run Venezuela’s companies have to be bought abroad. Hell, even PDVSA is exposed! Without imports of light oil to mix with domestic heavy oil so the damn stuff will flow through pipelines, its production would wither!

Obviously, when dollars to bring in those imports dry up, things start to go wrong. La economía empieza a pistonear por todos lados, and soon you’re traumatizing your children with Breakfast Cereal that looks lifted straight out of some Tropical/Soviet mashup dystopia.

Even companies that “produce in Venezuela” come to rely on those black market dollars for their intermediate supplies (a.k.a., whatever-their-equivalent-is to the Zucaritas packaging ink.)

Of course the impact of the import cut isn’t equally distribubed. The cut hit the private sector disproportionately hard: for the first time —likely, ever— most imports now come in through the government. Econanalitica estimates that, when detailed statistics are out, it will account for 62% of imports in 2016. The previous year, it had been the other way around. So, there are not enough dollars so people can eat and the economy can function, but of course there are plenty to keep the government’s power players happy with their share of the ten-bolo dollars.

Unable to get enough official dollars to run its plants, the private sector has been hitting the black market, hard. Ecoanalitica, again, thinks 28% of private imports are carried out with black market dollars, up from 22% in 2015. That helps explain why non-price controlled goods have seen prices go haywire: even companies that “produce in Venezuela” come to rely on those black market dollars for their intermediate supplies (a.k.a., whatever-their-equivalent-is to the Zucaritas packaging ink.) Those hikes get passed on, inevitably, to the final consumer.

The Venezuelan economy’s reliance on imported intermediate goods, supplies and inputs is the reason Miguel Angel Santos likes to say that one not-terrible approximation to Venezuelan GDP is just to take your gross imports figure and multiply it by 4 or 5. It’s not the world’s most subtle estimation mechanism, but it nicely captures this basic insight that vast swathes of the Venezuelan economy just can’t work without imports.

This, beyond food, is why Maduro’s import figure announcement yesterday was so shocking. Because, remember, Kellogg’s is actually one of the fortunate few: the import crunch hit their packaging division. This made them look ridiculous, but it didn’t make them shut down.

For many other companies in Venezuela, no money for imports means nothing gets produced. Period. And that’s not grrrrrreat.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate