The Venny Bond Outlook 2017: Out of the woods?

Venezuela shocked markets once again by sustaining its suicidal willingness to pay. Can Maduro sustain this high-wire act performed by a drunk, who has vertigo?

2016 is ending on a sour note for Venezuela. Awful headlines on the political front (face it MUD, you let us down) paired with an increasingly unhinged economic discourse have left us with a depressing, surreal state of affairs: a government that’s utterly paralyzed in the midst of a country visibly falling apart. To top off a year of #TropicalMierda, Maduro unleashed the Cash Apocalypse, spawning a hellish weekend in Ciudad Bolívar that many fear might turn into a nationwide social explosion.

Through it all, the Republic and PDVSA have continued to pay their external debts for yet another year – with difficulties, grace periods and “voluntary” debt swaps, sure, but paying.

Our view was that, while praying for oil prices to bounce back, the government would continue to pay its debts at all costs

How come?

Back in March we set out our playbook for 2016. Our view was that, while praying for oil prices to bounce back, the government would continue to pay its debts at all costs; even if that implied a savage cut in imports of consumer goods, creative sources of financing (such as the exchange of PDVSA accounts payable into promissory notes, the ‘swap’ of the PDVSA 2017 maturities for the PDVSA 2020 notes backed by 50.1% of Citgo Holding’s shares, and the Rosneft loan backed by the remaining 49.9% stake), and a barely-enough bounce in oil prices. All of this, ultimately, saved the government’s arse this year, en la rayita.

The ‘suicidal willingness to pay’ thesis has paid off handsomely in terms of returns for bondholders. But at incalculable financial and welfare costs.

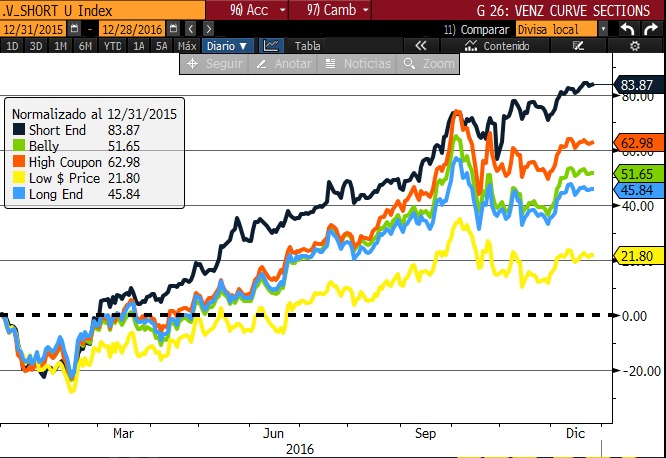

2016: The year of the Bond Bachaquero

The Bachaquero of Wall Street lives and tops the charts for 2016: Short-end bonds (Debts that are due in 2018 or earlier) were the best performers in the year, as the government executed its pay-at-all-costs policy. Within the short-end, the PDVSA bonds due in 2017 outperformed the rest: in the space of less than a year, the papers went on to trade from below 40 cents on the dollar, all the way up to 90 (in the case of the “olds” that mature next April). The market was fully expecting PDVSA to go bust before the end of this year and was blindsided by Maduro’s commitment to paying the country’s debts at the expense of mortgaging and selling the resources of the Republic.

Ironically, being last in line in Venny still amounted to an outstanding 22% return.

Not surprisingly, this also meant that long-term investors, especially those invested in the lowest-priced PDVSA bonds (such as this vulture fund) dramatically underperformed in the year; ironically, being last in line in Venny still amounted to an outstanding 22% return, underscoring the huge chunk of value pinched by Venezuelan bond forks off all shapes and sizes in 2016.

2017 is a whole new game

2017 is a whole new game

Looking past 2016, there’s a tough road ahead for Venezuela and PDVSA bonds.

For several years, as we have seen the breakdown of, well, everything in Venezuela, the Venny market has worked like clockwork: an alternate reality completely disconnected from the day to day of the country. That changed in 2016, for good.

Debt service is running on fumes like never before, constantly counting on a last-minute loan from Wall Street or a friendly country to keep going.

Maduro showed his willingness to go to extreme lengths to keep paying off Wall Street (even if that meant letting el pueblo go hungry). But the government’s stance reeks of desperation, enough to shatter the illusion that they retain the capacity to pay. Grace periods, debt swaps, extension of commitments: they used and abused every trick in the book to stay afloat. Debt service is running on fumes like never before, constantly counting on a last-minute loan from Wall Street or a friendly country to keep going.

That’s why a credit event on PDVSA or the Republic sometime during in 2017 is a high-risk, high-probability outcome.

The facts speak for themselves:

- Venezuela and PDVSA face a debt service tab close to $10 billion for 2017, plus several billion worth of non-bond financial commitments, including bilateral bank loans, promissory notes, ICSID award payments, Chinese Fund amortizations, etc. etc.

- International Reserves stand slightly above $11 billion at the end of 2016. The government doesn’t appear to have enough liquid assets to deplete to cover next year’s debt service.

- There’s uncertainty about what the Reserves number really represents: if those gold ingots are still in Carmelitas, it’s about the only thing that hasn’t been stolen there.

- At current oil prices and production levels, economists forecast a $10-12 billion gap in the Balance of Payments. I’m hard-pressed to come up with alternative financing sources that don’t involve stuff like pawning a Caribbean Island or privatizing CANTV. Where’s the money going to come from?

- The swap of PDVSA 2017 bonds in late October showed the government’s ugliest face. “Options are options”, as Eulogio Del Pino’s aide infamously said in a conference call to investors in the midst of the deal. The government’s threats to suspend payments if the deal didn’t went through were far out of bounds; a hostile tactic that will cost them dear when the time to tap the capital markets comes again.

If you couple these unpleasant facts with a compelling normative case and a roadmap for suspending debt service, brought forward by Joe Kogan in the NY Times, the idea of an Event for 2017 stops sounding so scary and starts making sense.

Too bad that Maduro’s in power and making sense has never really been his thing. ‘Suicide willingness to pay’ will probably stay until the money just plain runs out. This opens the possibility of a messy debt default, the worst possible outcome for the country. We don’t know rock bottom yet.

The government still seems to be banking on a surprise recovery in oil prices, brought forward by the OPEC/Allies output cut, that will solve everything, according to Héctor Rodríguez. Maybe. Maybe not.

Politics, front and center

Domestic politics are going to be vital in understanding 2017 and how the ‘endgame’ unfolds. Maduro’s popular support seems to have a floor at around 25%, below which he won’t go no matter how bad the situation gets. That’s a relatively high floor — high enough to keep him in power so far, in particular as the opposition blundered its way through 2016 and finished the year morally defeated.

Against this backdrop, I wouldn’t expect regime change in 2017. But stranger things have happened.

Against this backdrop, I wouldn’t expect regime change in 2017. But stranger things have happened. Three scenarios come to mind for next year:

- A ‘willingness to pay come-hell-or-high-water’ with Maduro still in power is our central scenario, with the government continuing to draw down hard assets. This is a dangerous and destructive policy as the very high cost of borrowing together with an economy in full-blown depression, means the dollar debt burden (as % of GDP) is growing at an almost-exponential speed. And it opens the possibility of an accidental, lack-of-capacity-to-pay default. It’s a high-wire act performed by a drunk. Who has vertigo.

- On the other hand, an opposition-led government would most likely restructure the external debt, either backed by the IMF or not (if for example China pivots towards a new government, which I don’t think its that crazy if you ask me). Besides the main obstacle of what does the MUD have to do to translate its majority in the popular vote to actual de-facto decision-making power, there’s an issue on what to do with PDVSA’s debt burden, not made any easier by the lack of Collective Action Clauses and a capital structure that is getting more intrincated by the day. A proposed solution that includes declaring a domestic bankruptcy, put forward by Ricardo Haussman and covered by our in-house bond guru, Javier Ruiz, is politically very hard to sell, but offers a way to avoid a messy Argentine-style scenario. So it would entail a default as well, but done in an orderly and planned way.

- There’s a third, possible and scary scenario, on which a more pragmatic wing of chavismo gets rid of Maduro after January 10th and takes over the country and keeps transition “in the family”. This administration would most likely maintain the willingness to pay, but could dramatically improve ability to pay as well simply by getting rid of the worst of the Maduro-era distortions (such the multiple exchange rates and basically-free fuel and electricity). In this context, and given a benign oil market for the foreseeable future, the Venezuelan economy could turn around, or at least stabilize, enough to avoid spiraling out of control. Of course, imports will remain at grotesquely low levels, but nobody on Wall Street really cares about that.

If oil prices don’t recover at least enough to cover the Balance of Payments gap (say WTI at or above $65/barrel) the probability of a credit event is extremely high. Whatever happens in the political arena will determine which of the three scenarios described above will unfold; two of which (#1 and #2) will lead up to a default.

There’s a big caveat, though: if oil surprises on the upside and climbs up past the 65$ mark, then chances favour the Republic and PDVSA muddling through another year without a regime change.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate