We Guayaneses Were Into Basic Goods at International Prices Before It Was Cool

The government's decision to allow basic staples to be freely sold in formal shops at international prices has been a novelty in Caracas this week. In Ciudad Guayana, they've had it for months.

It’s one of the great frustrations of my profession: for the most part, economists can’t run experiments. We’d love to take out a petri dish and add, say, a bond swap in a certain oil company to see the market’s reaction. It would be so cool. But it can’t be done, so we rely on models and are always on the lookout for real world situations that replicate an experiment somehow.

That’s “el deber ser”, but that’s not how chavismo rolls. Their notgiveafuckness allows them to try out half-baked ideas on a grand scale without bothering about trifles like feasibility studies. Chavismo turns whole cities into petri dishes with their “pilot plans”. Often, these are horribly misguided, so being the test case means you’re the first to suffer the consequences when it all goes wrong.

When Vielma Mora announced his plan to supply Caracas with imported products at international prices, I got another bit of hipster frisson: we’ve had that for months.

The farther the city is from the capital, the crazier the experiment.

Enter Ciudad Guayana, truly a petri dish of a city, we sport a non-functioning public transport system called the Transbolivar. Actually, whatever is going wrong where you are, we were way ahead of you: we had water and electricity rationing long before “El Niño” was even a thing, the smart patrolling started out in 2013 for us, and we had the chronic product shortages way before it made it to the Caracas headlines. Malaria, difteria…you name it, we set the trend.

So when Vielma Mora announced his plan to supply Caracas with imported products at international prices, I got another bit of hipster frisson: we’ve had that for months.

When our (literally) starving market got even this tiny, insanely-priced new source of supplies, everyone freaked out. Suddenly the shelves were full of rice, pasta, wheat flour, cooking oil, even sugar.

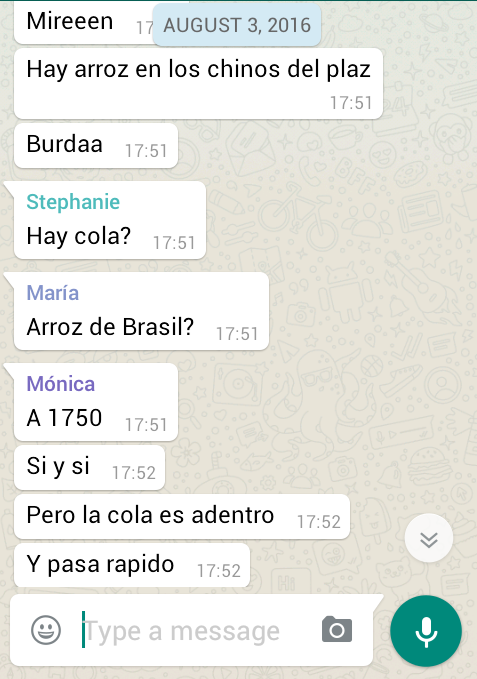

Check out the date…

The first week, Whatsapp chains like this started going around. Excitement wore out quickly, though, as people quickly realized that at these prices, products just don’t run out.

That’s the crazy thing that happens when no one is forced to sell at a loss. Once I was in a birthday party and all the cumpleañera could talk about was the cake, and how she was able to find all the ingredients with ease, no shady intermediaries, no phone calls. Some bachaqueros even got some, but it was pointless: you could find it cheaper at the stores.

All they did is bring bachaquero prices indoors.

This forced the bachaqueros to actually compete and lower their prices, but just a little. When the dust settled, the lines were still there. The hunger, too. In my house, the Brazilian stuff is a complement: we bought sugar a couple of times to make juice, and once we made an pumpkin cake with the wheat flour, but that’s about it.

All they did is bring bachaquero prices indoors.

The pasta is sticky, the wheat is salty and the sugar sometimes comes with some kind of metallic residue you have to take out with a magnet. Right now, people are so desperate no one is worrying about sanitary regulations or proper permits. All the packages are in portuguese only, and the are no sanitary labels to be found. The parties involved (lots of GNBs among them) can get away with it because the bar is really low for them, their competition are the bachaqueros, who aren’t afraid of selling you a carrot for toothpaste.

So, Caraqueños, don’t get your hopes up. This kind of piecemeal reform, that happens without an overarching strategy to overhaul the productive system and really get on top of pervasive price distortions, isn’t really much use to anyone.

If you happen to be rolling in cash, there’s some marginal benefit to being able to buy this stuff at a store rather than from a black marketeer. But for the vast majority of people, little will change: tomorrow, you won’t be able to afford what you can’t find today.

Se los digo yo que vivo en el futuro.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate