A Day in the Life of Nicolás Maduro's Community Manager

Yenireth Molina realized there was something different about her early on. At first, she thought it was God. A little voice inside her head telling her she would be protected as long as she prayed four Hail Mary’s while she washed her hands, and that she should always turn off the faucet with her left hand. She realized it was not God when those Hail Mary’s turned into 16, and the faucet closing ritual included turning the lights on and off eight times.

Everything she read, she had to read twice because one is an uneven number. Any task required of her had to be completed —till there was not one pea left on her plate. Sounds like a virtue, but it was a curse. The voice in her head wouldn’t go away. Only much later would she understand that that voice made her the perfect candidate for her current job.

Yenireth is afraid of elevators; she walks up the stairs. Fortunately, her office is on the 8th floor of the building, there’s 16 steps per floor, and 128 in all. She walks fast, and with each step she feels every muscle in her lower body burn a bit, it takes her 4 minutes to get there. Never more, never less. She’s fit, but she never tries to push under those four minutes. She uses her right hand to slide her key card, and by muscle memory uses the same hand to swing open the door, she has maybe two seconds do this before the buzzer shuts the door again, but she never misses. It takes her 16 long steps to the eighth cubicle in the hallway, the one she insisted on when hired.

Yenireth, or Jenny, which is how she signs her emails, made her way into SIBCI almost despite herself. She was finishing an internship at one of the grand old newspapers where virtually every last decent journalist had walked out in disgust under pressure from the bolifronting new owners, when her tidy ways and nitpicking nature called the attention of her new bosses.

She was drafted into a new, special communicational counterterrorism unit. At first, it sounded exciting to her. Glamorous. But then she realized there wasn’t much to it. Mostly handling several twitter accounts to comment on several prominent public servants’ twitter messages. It wasn’t really hard, and in her hands, it got done with the obsessive thoroughness she brings to everything.

Jenny gets to her seat, and picks up a red sort of ski patrol jacket from the seat-rest, wraps herself in it, and fires up the PC. The smell of the jacket always reminds her of the first time she wore it, and how proud it made her feel to walk around in it. It was no corporate ju-ju she had fallen for, it wasn’t some ideological thing, it was just the way it opened doors for her and the folks at work when they would walk in uniform to the mall on the other side of the street.

She doesn’t wear it outside of the office anymore.

Most people on her floor don’t quite know what she actually does. They think she spends her days, like them: trolling people on the internet and writing positive comments on President Nicolás Maduro’s Facebook wall. They don’t know she actually manages the president’s Facebook page.

She doesn’t talk about it because, actually, she was demoted into that position. She used to be on the President’s Twitter account team, and she did brilliantly at it. Until an episode with the President himself. One day he insisted on showing the country, on live TV, that he could compose tweets and write response in real time.

That day was huge for her. She was given the honor of tutoring the President right before the cameras went on. All the instructions of her interaction with the President came from a thin, dark skinned, handsome young man who wouldn’t leave the President’s side.

“Don’t worry, if you explain things to him slowly, he’ll understand. You’re going to do great.” And great she did, the President got it perfectly, even when she was a little awkward while talking to him. Some people simply repelled her. She couldn’t touch him, or look him in the eye. As if she were to catch some weird disease from him, something that would turn her into, well, him. It was strange, and not with everyone, and certainly not with the young assistant.

In the end she pulled through, Maduro did great sending his tweets, although the syntax had its issues, he seemed really happy to be able to interact with the technology, and to see the live effect of his tweets. Everything was fine, until he started reading some of the responses he got. He read them aloud, again, on live TV. He read insults against him, went through them before realizing what he had done.

When they went off the air, the President went ballistic. He screamed at Jenny’s face, right up close, on and on. She couldn’t move and she felt how Maduro’s saliva sprinkled on her forehead and her cheeks. There was no way of escaping the infection.

Jenny was fired on the spot by the President himself. At the moment she couldn’t quite understand what had happened, and had an uncontrollable urge to burst out of the theater as fast as she could, and cry her guts out.

She was standing on an escalator to go down to the parking lot, still sobbing uncontrollably, when she felt a soft, gentle hand grabbing her wrist. It was the young assistant. As they got off the escalator he sort of waltzed around her still taking her by the wrist and pulled her out of the way of some fat politicians that were behind her. She didn’t mind his touch. Weird. He took a handkerchief out of an unusually large laptop bag, and wiped her tears. Gerardo apologized for what happened, and promised he would find her a new job.

A couple of days later she got a call. And it was perfect, the pay was as good as before, and she wouldn’t have to deal with too many bureaucrats, or military men, or Presidents. It was just a quiet office, where no one needed to know she’d be helping to manage the Presidential Facebook page.

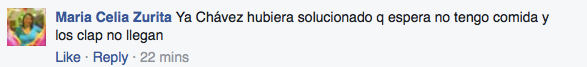

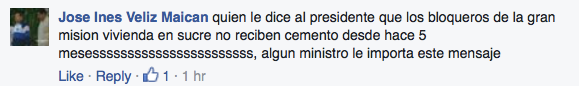

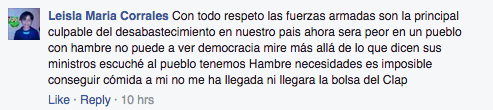

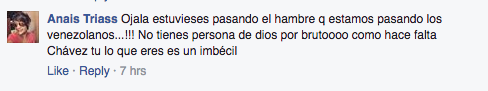

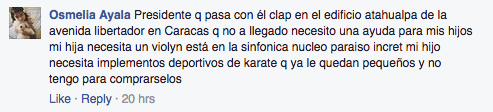

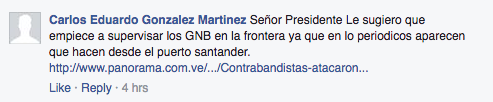

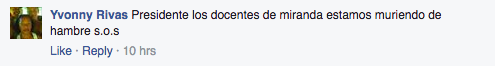

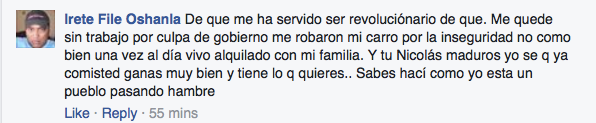

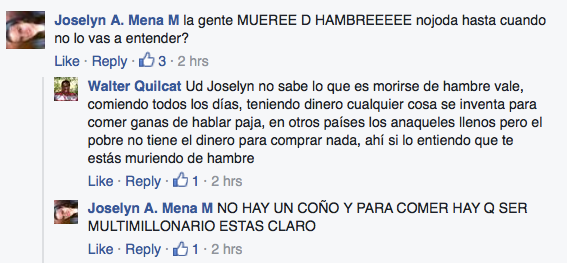

In general, her job is simple. She’s supposed to keep Maduro’s Facebook wall clean, where “clean” means: no insults, no misery, no opposition, and no threats. If more comments are needed on a given post, she sends an email, and an army of virtual patriots decorate the wall with praise for the President and the Revolution.

At first Jenny was like a ditch, a safety net, catching all negative comments, obsessively. Nothing got past her.

The curse seemed to work as well as ever. She still read every single comment. Twice. Even the ones she knew she would erase at a glance. It was overwhelming.

Yenireth started dreaming of sick children, of mothers dying of cancer. Of bags of groceries that didn’t get to their destination, of families waiting anxiously for them, wondering if their time was better spent trying their luck in line. Of murdered loved ones, of hunger, of forlorn job-searches. Of threats. Of insults.

As she deflected all the hate aimed at the owner of the account, she started feeling the spit on her face again. She spent days dredging, twirling in bed at night, feeling herself morph into something… something else. She could feel as she was transforming into Nicolás Maduro.

And it seemed there was nothing much she could do to stop it. Except one thing.

And it seemed there was nothing much she could do to stop it. Except one thing.

Let go.

The only way to reverse her metamorphosis was to let go of her obsessions. Let all that crap get into the Facebook wall, and off of her. For her to get clean, the wall had to get dirty. Who cares? Not her. Her days go by and she does nothing, and it’s so much better than what she dreamed it would be. It’s like Maduro pulled off what a dozen doctors couldn’t. He cured her. Well, almost entirely.

She still makes sure there’s an even number of comments by the end of the day.

Yenireth Molina sits in front of her computer, fixes her glasses, and opens a chat box on her Facebook page.

How’s your day so far? <3 <3

Typing…

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate