I Witnessed CNE's Signature Verification Process and None of It Made Any Damn Sense

Randomly invalidated forms, impossible standards, arbitrary obstacles...take a tour of the Electoral Council's idiotic signature validation process with me.

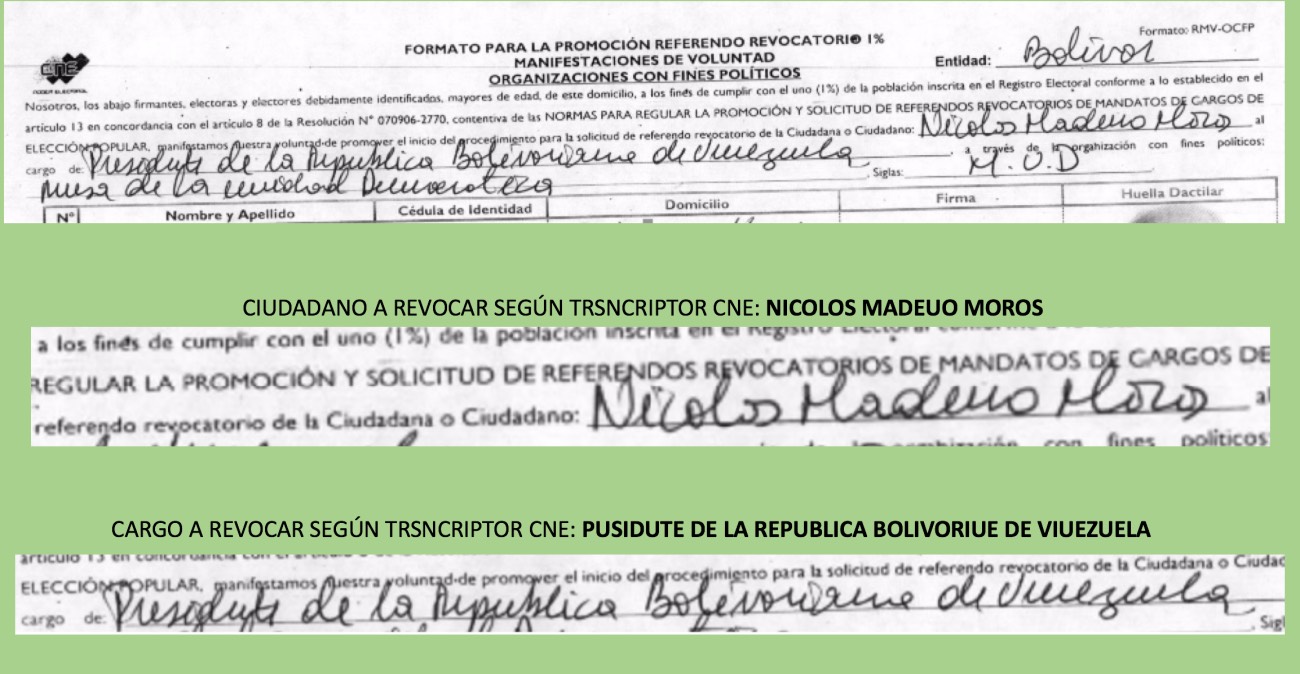

.“Of course that’s not an ‘S.’ It’s clearly a ‘D’…” says the CNE supervisor.

The PSUV witness concurs. “The top of the form reads “Nuols Modwo Moud,” he says.

He’s talking about the handwritten bit at the top of one of the 200,220 forms calling for a recall referendum for the president. Like most of the forms, this one has 10 signatures. The person in front of me is telling me with a straight face that they cannot accept those signatures, because the people who signed them intended to recall some mysterious person named “Nuols Modwo Moud”.

There was, of course, no need for CNE to leave the spot for the president’s name blank, other than to create one more bullshitty excuse to reject forms.

It’s been a tetchy few hours this day inside the hastily set up CNE office in La Urbina, where the signatures are being digitized and transcribed. The screaming back and forth over this kind of minutiae has been going on all day. Five MUD witnesses have already asked to leave the room because they frankly couldn’t take it anymore. That’s when I got called in to help out as a witness – when every last one of MUD’s experienced, battle-hardened witnesses walked off in disgust at how unfair the whole procedure was.

There was, of course, no need for CNE to leave the spot for the president’s name blank, other than to create one more bullshitty excuse to reject forms. The scrawled handwriting, usually cursive, at the top of the forms is a testament to the uneven quality of our education system, ranging from the delicate to the close-to-illegible. Each time one of the forms’ heading is judged less than 100% clear, ten more Venezuelan citizens are deprived of their legitimate political right to petition for a recall referendum against Nicolás Maduro Moros.

That’s just one of the beyond-ludicrous extremes to which the CNE has gone over the last few weeks to delay the process (clearly laid out in the law, BTW) that would lead to invoking a referendum to recall Maduro’s mandate as President.

It’s now been one month since the signatures were delivered to CNE’s galpón in Filas de Mariches that dewy morning of May 2nd. According to the CNE’s norms, what should’ve happened is the following: they would take five days to revise the signatures, and then go on to the biometric validation phase, which is CNE-speak for “everyone who signed must now show up in person and scan their thumbprint on our nifty captahuella machines, so we can make sure you’re the same person who signed and you’re not dead.”

CNE improvised a slew of redundant and laughably inefficient steps for “revising” signatures that, aside from adding 30+ days to the legally established five-day period, also calls into question their claims to basic integrity.

Techincally, this meant transcribing all the cédula (I.D.) numbers of signatories, cross-checking them through the National Voter Registry (REP), and loading valid entries onto the fingerprint scanner database for biometric validation. Fair enough.

Instead, the CNE improvised a slew of redundant and laughably inefficient steps for “revising” signatures that, aside from adding 30+ days to the legally established five-day period, also calls into question their claims to basic integrity.

Two days after signatures were delivered on May 2nd, CNE began what they arbitrarily defined as the “Process for Counting Signature Forms.” This took place over the course of six days, in the CNE’s logistical headquarters (a.k.a., galpón) in Filas de Mariche. The mammoth warehouse in the industrial sector of Eastern Caracas sits atop a hill surrounded by slums and factories. It’s home to all the voting materials, from fingerprint scanners, voting machines, ballots, security ink and vehicles, to be used nationwide any time an election happens. As is standard for any heavily fortified official building belonging to the Venezuelan State, a handful of stray dogs roam around looking for shade, relying on the National Guard unit deployed on site to purvey scraps of their chicken and rice meals for food.

Every morning, for six days, around 45 MUD and PSUV witnesses would line up, single file in front of the vast warehouse – otra cola más.

Every morning, for six days, around 45 MUD and PSUV witnesses would line up, single file in front of the vast warehouse – otra cola más.

After clearing a security checkpoint and being stripped of cell phones, cameras, wallets or pens, we’d be allowed inside the sacred entrails of the warehouse, and be made to wait for what seemed like an overly-ceremonious spectacle of extracting the signature boxes from the CNE vault. Witnesses from both parties would then flank CNE operators stationed at individual tables.

Mitchell, the young man I was assigned to supervise, almost fainted from a dizzy spell due to the heat.

The operators were mostly young, minimum-wage earning workers who were visibly annoyed by the pointlessness of their task: to hand count, one by one, the signature forms contained within every envelope. 100 forms per envelope, 25 envelopes per box, 80 boxes in total. The warehouse had no air conditioning, and sweaty operators had to stand during the day long, 10-hour process.

Mitchell, the young man I was assigned to supervise, almost fainted from a dizzy spell due to the heat. Us witnesses were not allowed to touch the forms or interact with the operators. Any objections to the counting process, which each operator designed according to their criteria (Mitchell preferred to keep count in his head, although the persistent interruptions by the PSUV witness would make him lose concentration and he would have to start over from scratch), would have to be reported to the MUD or PSUV supervisor.

Although operators would finish counting forms at mid-morning, and would ask for additional boxes to be made available, CNE decided that only one box would be counted by an operator per day. Even though I had a MUD nametag prominently featured on my shirt, spontaneous demonstrations of dissent by government officials were a constant during my day in Mariches.

“I was part of the Presidential Guard during Chávez’s term,” said to me one of the CNE guards on duty. “I don’t agree with this process at all.”

The only value-added of this six-day ordeal of hand-counting? Let the record show that 200,220 forms were tallied, of which 21,620 had some empty spaces. That’s it.

The CNE then took three additional days for the purposes of transporting sensitive electoral materials to a rented space in La Urbina, the next process of “Digitizing and Transcribing” began on May 17. If I still have your attention, allow me to tell you the mind numbing details – if only to justify the oodles of time I wasted there.

CNE outsourced this phase to a Panama-based company called HiSoft (the Venezuelan government is their only client). Over 200 employees were brought into a nondescript building, the insides of which were hastily plastered with official-looking CNE decals on every door. National Guard soldiers guarded the entrance while typing somberly into their smartphones.

For two days, these employees were given training and methodology by CNE behind closed doors, and were then put to work scanning and transcribing the forms containing the expressions of people’s political will.

Rows upon rows of brand-new, ultra high-performance computers, equipped with autonomous backup energy cells, were set up in enormous, air conditioned rooms where some operators scanned signature forms, while others transcribed every single letter handwritten onto them.

The thing that lays CNE’s bad faith bare, the thing that broadcasts its voter suppression agenda for all the world, is the insane decision to invalidate the entire form (10 signatures, remember) due to any minor mistake filling out the top of the form.

Curiously, none of the transcribers was given access to the REP, the online voters’ registry that the CNE conveniently offers to anyone with an internet connection. It would’ve been logical and straightforward for them to be able to run a quick check of a cédula number when they couldn’t quite make out a person’s handwriting. But CNE doesn’t do logical and straightforward.

Instead, transcribers were left to their own devices when deciphering calligraphy, which is why, if your name is María Pérez, chances are it got transcribed as Mario Poros…and your signature got rejected.

But ok, the poor transcribers were putting in 12 hour days doing mind-numbing work through no fault of their own, so they get the benefit of the doubt. I’d even be willing to give CNE a pass for striking shoddily written names and last names as invalid.

But the thing that lays CNE’s bad faith bare, the thing that broadcasts its voter suppression agenda for all the world, is the insane decision to invalidate the entire form (10 signatures, remember) due to any minor mistake filling out the top of the form.

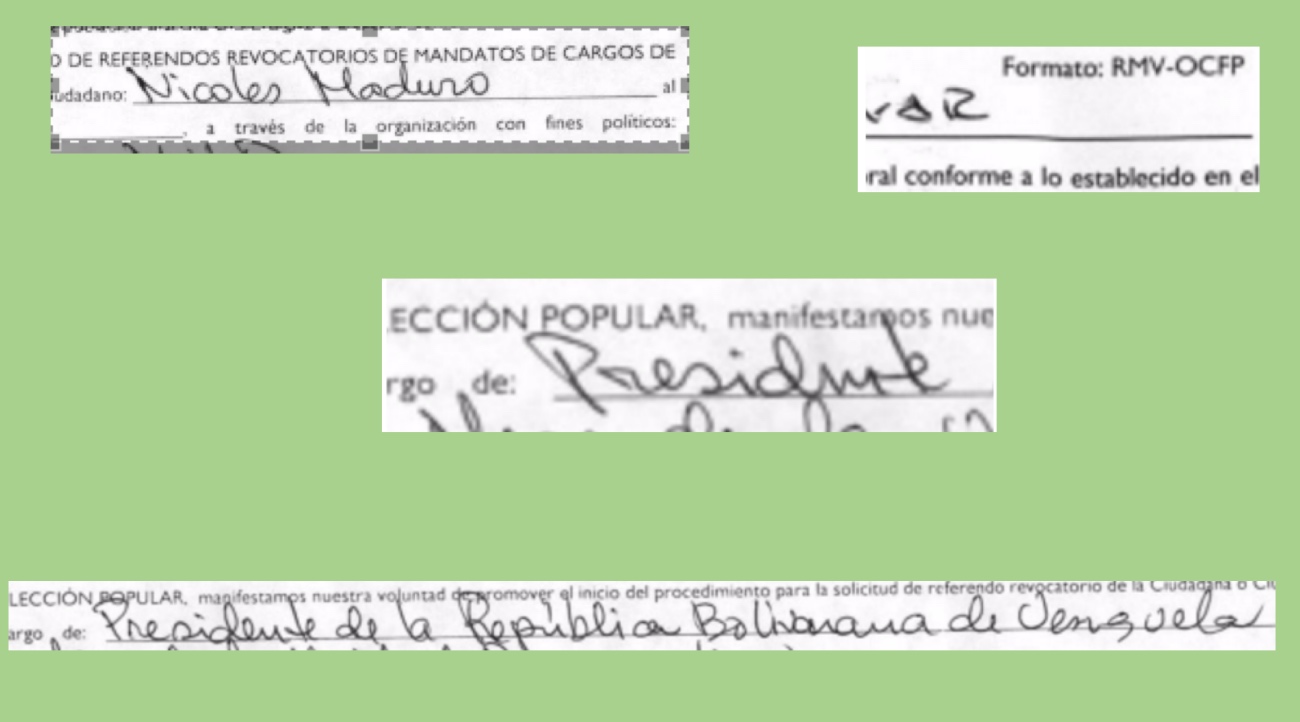

If “Presidente” is spelled with a “C” instead of an “S,” then the form, and its 10 signatures, is invalid.

If “Maduro” was written in messy cursive, and can thus be read as “Madoro,” then the form, and its 10 signatures, is invalid.

If —as I witnessed on one form— the state on the letterhead was written as “Libertador,” which doesn’t match the official name “Distrito Capital,” then the form, and its 10 signatures, is invalid.

Here’s a taster platter of mistakes that got whole forms disqualified:

Shouldn’t it be the mandate of the autonomous electoral power to make every effort possible so that the largest number of voters may indeed express their will, despite shitty handwriting and faulty spelling they’ve been burdened with by the subpar state education system?

Shouldn’t it be the mandate of the autonomous electoral power to make every effort possible so that the largest number of voters may indeed express their will, despite shitty handwriting and faulty spelling they’ve been burdened with by the subpar state education system?

Over the course of 12 days, this “Digitizing and Transcribing” process involved 6.5 phases: The scanning of all 200,220 forms, the double transcription of all their contents, the auditing of names that the system rejected because they did not match the REP, the going back and starting from scratch on the forms that were not fully transcribed because ladillado operators went out for lunch (that’s the .5 part), the revision of fingerprints by dactiloscopers (who did not validate prints against a registry, but only made sure that they were “readable”), the revision of handwriting by graphologists (who did not validate handwriting against a registry, but only made visually sure that all signatures on one form did not show similar patterns), and the auditing of transcription errors (which, when identified, were merely counted as such, and not corrected).

Despite the arbitrary invalidation of signatures that CNE achieved during this audit, there’s never been any real doubt that MUD has the 197,000 signatures needed for the referendum process to advance, many times over.

Preliminary numbers from MUD technicians, based on CNE audits, reveal that only 0,065% of fingerprints could be considered duplicated, and that 1,51% of signatures could be considered suspect.

Jorge Rodriguez begs to differ.

Despite the arbitrary invalidation of signatures that CNE achieved during this audit, there’s never been any real doubt that MUD has the 197,000 signatures needed for the referendum process to advance, many times over. The entire, byzantine foot-dragging process is as unnecessary as it is undemocratic.

This process of revision finished on Tuesday, May 31st. That’s 29 days longer than the deadline that CNE itself established. MUD could have, should have kept the heat up throughout, running a real-time color commentary on these idiotic shenanigans. It never did. To my mind, they were almost as negligent in airing out CNE’s malfeasance as CNE was guilty of perpetrating it.

This is the most advanced electoral system in the world at work: a bizarre, pointless contraption openly designed to suppress people’s political rights.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate