Undeveloping Country

It's time to table debate on what to do with the oil rent, and start thinking about how the oil industry cannot bear the weight of an entire economy. But first, we must understand how this all came to be.

It’s an opposition mantra: the Chavista economic model has failed Venezuelans and it’s time to move on. Personally, I have no intention of defending chavismo’s legacy of economic mismanagement. But that’s a far cry from stating that the model was broken by the late President Comandante Eterno. Truth is, the model has been broken for a while.

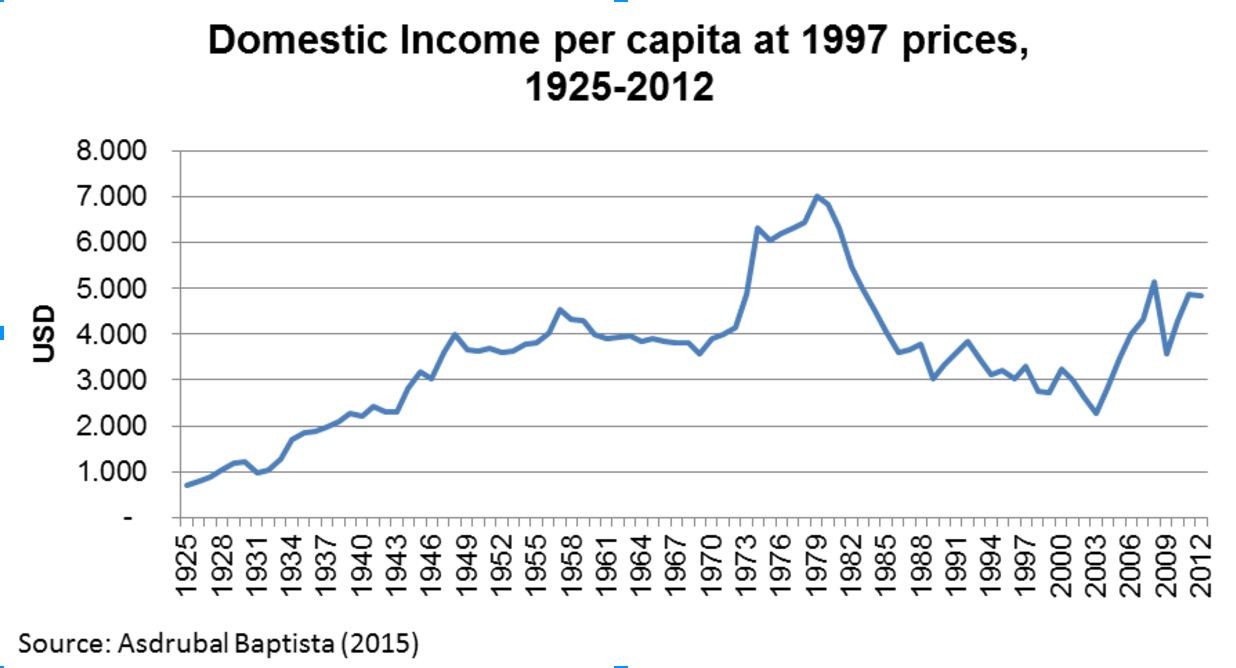

For example, did you know that income per capita in Venezuela started decreasing in real terms since the late 1970s? Of course you know. We’ve all heard the stories of the Saudi Venezuela and thought to ourselves: Why couldn’t it stay that way? Why?! But looking at the chart helps put things into perspective.

As you can see, Venezuela had a spectacular run between the 1920’s and the 1970’s. That’s 50 solid years of sustained growth, during which the economy grew tenfold. So, what happened? Why did we stop growing?

The answer lies in our institutional foundations, those silent heroes which allow the national government to pursue a winning strategy while relying on an external and volatile financier like the international oil market, instead of letting productivity work its charm by telling us what we’re good at, and what we’re not. Yet despite having over one century of oil history to look back on, Venezuela’s oil institutions, and the intrinsically linked economic model, have never quite found their footing.

The easiest way to understand our current economic model is to know how it was built. So, here goes a little bit of contemporary history.

How the model came to be:

That’s what made consumption explode in Venezuela like never before: we were buying development with petrodollars.

Oil turned things around for Venezuela during the 1920’s in the hands of General Juan Vicente Gómez. Although most of the chitchat about those days centered on corruption scandals, the breaking point of that period was that, for the first time, a poor country like Venezuela started to collect income taxes and royalties from the most lucrative industry in the world.

Oil windfall was so large that Gómez was single-handedly able to pay all of Venezuela’s foreign debt going back to independence, and start the first large public infrastructure program.

Among other things, four central features of Venezuelan economy were set under his rule:

- A close relationship between the oil industry and the country’s President, because he was the one handing out the concessions.

- An artificially appreciated local currency, courtesy of the epic Convenio Tinoco.

- The empowerment of the national State as the main economic agent, since the stronger the government became, the less likely Gómez would be overthrown.

- The idea that the national Government should be responsible for administering all matters related to the oil business in the name of Venezuelans.

Oil then became the backbone of politics and public policy in our country, as well as the dominant sector of Venezuelan productivity, all at the hands of an almighty Executive Power.

The early success shown by the oil industry promoted a key piece of legislation: the Reciprocal Trade Agreement between the United States and Venezuela of 1939. Under the agreement, US companies would invest in Venezuela –not just in the oil industry, but also in commercial goods, heavy industry, airlines, tourism, retail, etc. – and, in exchange, Venezuela would be able to sell duty-free crude oil to US refiners. That’s what made consumption explode in Venezuela like never before: we were buying development with petrodollars.

Asdrúbal Baptista has coined the term Rentier Capitalism, an industrialization process based on capturing international rents derived from a scarce commodity as a means to reward capital investments, instead of depending on the creativity of national agents to become ever more competitive. Our factories thus never came to be because we were good at something, or because the market told us to make this or that, but rather because we had oil capital.

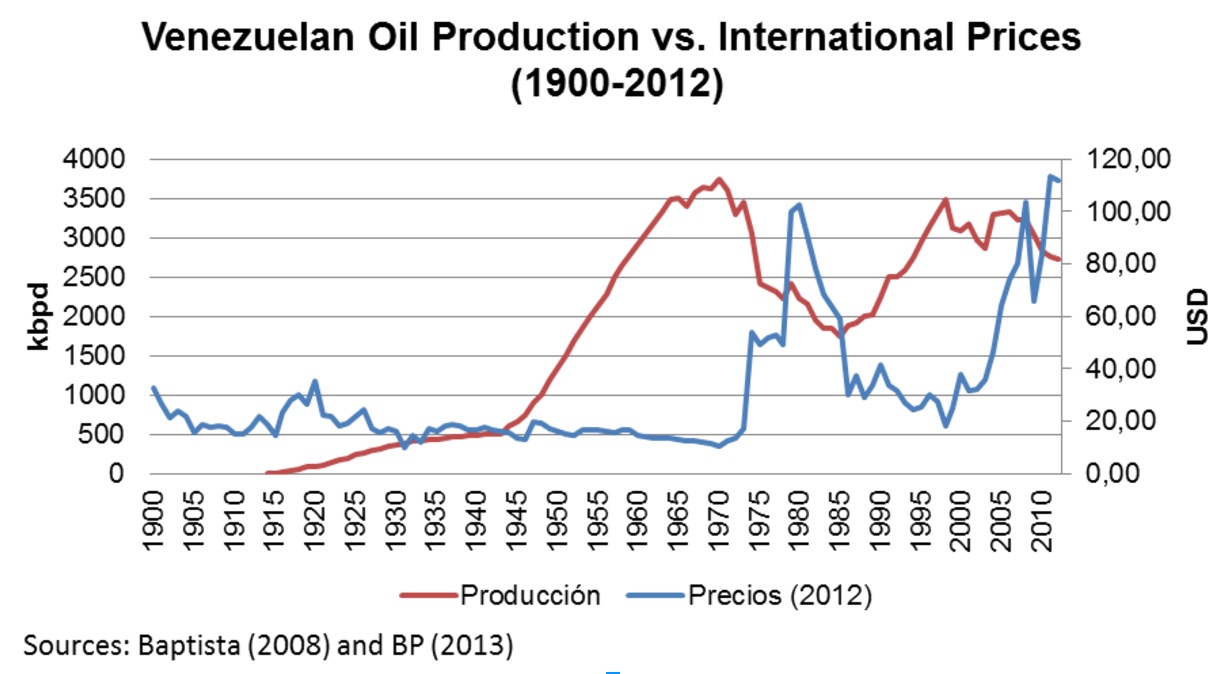

With the agreement, our country became the most important US partner in the region, a fact that President Medina Angarita leveraged to bargain with FDR for a new and more favorable framework for the oil business under the Hydrocarbon Law of 1943. The law simultaneously satisfied two sets of interests: it allowed the government to increase taxes on the oil industry, so they were able to blow up public spending. It also allowed foreign oil companies a 40-year timeframe to develop projects under new concessions, which, pushed by the World Wars, helped Venezuelan oil production to grow from less than 500 kbd in the 1920’s, to 3.7 MMbd in 1971.

Overall, the scheme through which the central government collected oil revenues and fed them into the economy through controlled initiatives seemed stable, but it had one big flaw: political opposition –back then, the leftist democratic movement– despised the idea of letting foreigners handle the country’s wealth.

Betancourt and Co. voiced their opinions on how Venezuela should nationalize its oil industry, asserting the premise that Venezuela was called to become a truly independent country, apart from the American empire and foreign interests –you may verify this in his book Venezuela, Política y Petróleo. Should the industry be nationalized, he said, oil revenues would be used to pay for cheap gasoline, universal free education and healthcare, and plenty other public services.

The nationalist narrative was powerful amongst the popular classes, which gained Betancourt’s Acción Democrática many voters to win the elections when the time came.

Puntofijo Democrats developed their own ideas about how the oil industry and its rent should be managed, but without reviewing Gómez’s ways.

When you put politicians in charge of a business, decisions back away from criteria like efficiency and productivity, and move closer to things like los lineamientos del partido.

Their first fully fleshed out petroleum policy was set out by OPEC promoter Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, of devil’s excrement fame. The Petroleum Pentagon, as he called his plan, had five lines of action:

- A reasonable participation in oil rights for the national government. This meant the government would try to maximize the rent extracted from the oil industry, based on the premise that hydrocarbon resources belonged to the national state.

- No more concessions to private agents, nationals or foreigners. Pérez Alfonzo thought oil was too strategic a sector to let private enterprises manage.

- The creation of a Coordinating Commission for the Conservation and Trade of Hydrocarbons. Amongst other things, the CCCH was in charge of determining the “fair price” of Venezuelan oil exports and dictate production levels since, in Pérez Alfonzo’s mind, the country was running out of oil.

- The creation of the first state-owned oil company in Venezuela: the CVP, which would progressively take over national operations.

- Maintain leadership in OPEC, in order to coordinate with other large stakeholders on a “fair price” for oil exports.

As you may realize, the Pentagon was still based on premises that allowed the national government to conduct the economy and increase central planning. They believed oil should be produced, managed and administered by the national state; private initiatives had to be rooted out like weeds. And we all know what happens when you put politicians in charge of a business: decisions back away from criteria like efficiency and productivity, and move closer to things like los lineamientos del partido.

This policy allowed the national government to grow more powerful than ever before. Larger quantities of oil revenue were captured by the national government, who then kept its promise to boost public spending. The State began spreading its corporate tentacles across the country, from banks to heavy industry, to electricity, dwarfing private investment in the most competitive sectors of the economy. At the same time, public administration grew quite large and social benefits skyrocketed.

How the model operates:

With the implementation of Pérez Alfonzo’s Pentagon and the new development strategy defined by the national government based on the distribution of oil rent and state owned enterprises, our economic model took the shape it still has today, and that we keep hoping will work again.

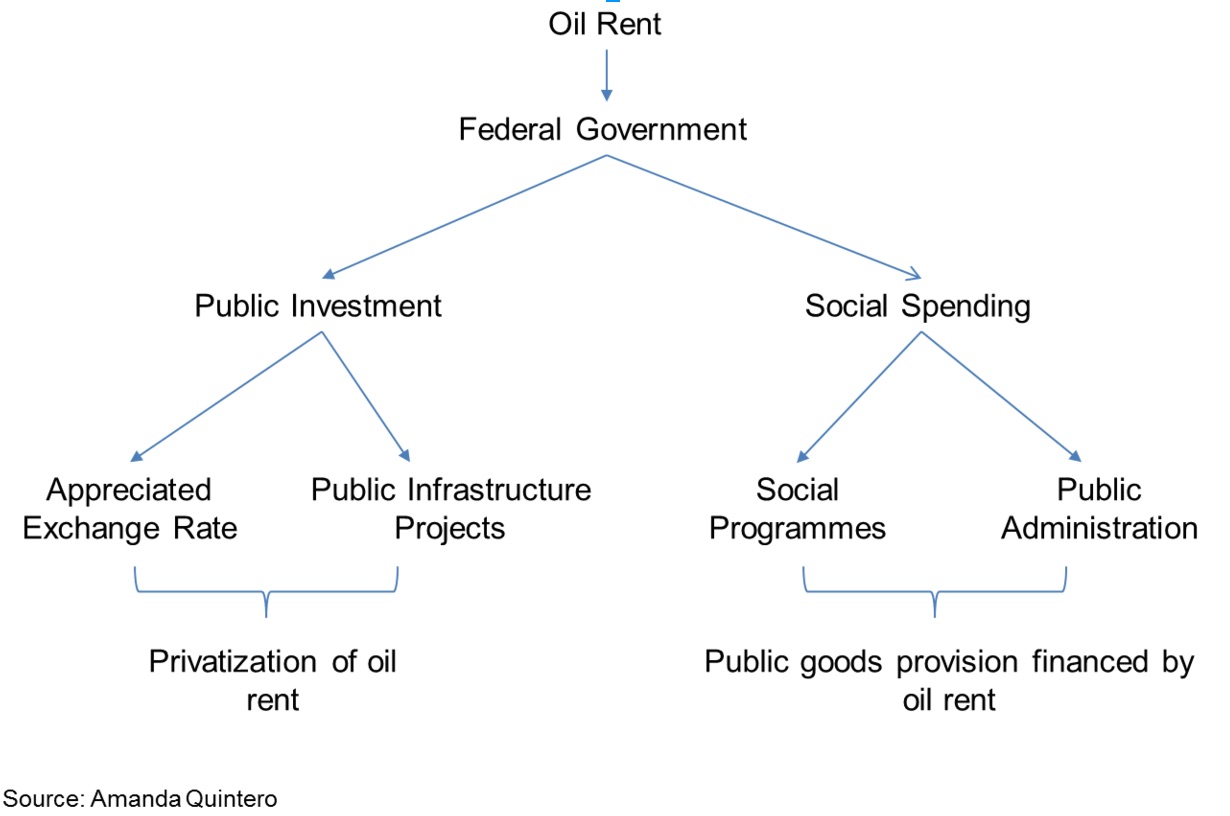

Oil is our main value generator. We develop the resources by extracting and refining our oil and gas, and later on selling its products abroad. Oil revenues are captured by the state through several forms of taxes and royalties, and a good deal ends up in the hands of the national government. Then, the government lets the oil rent flow throughout the economy through two channels: Public Investment and Social Spending.

The model only works when the combination (Oil production)x(Oil prices) goes up and outgrows population increase.

Public Investment refers to things like infrastructure projects and preferential imports. They benefit both from an artificially appreciated exchange rate and service contracts with the government. These mechanisms usually disproportionately benefit the business groups related to the government.

On the other side we have Social Spending, which is captured by an inflated public administration payroll, or directly on social programs; both elements are commonly used as propaganda instruments.

Once the primary rent has been captured, some groups invest it and add a limited amount of local value, mainly related to food production and services. The rest is simply consumed or saved overseas to be protected from recurrent devaluations:

As you can see, most of the economy’s value flows from the top down, creating a dependency relationship between those who capture and distribute the rent and those who seek and consume it. As long as the rent keeps flowing, everyone is happy.

As you can see, most of the economy’s value flows from the top down, creating a dependency relationship between those who capture and distribute the rent and those who seek and consume it. As long as the rent keeps flowing, everyone is happy.

How it all went downhill:

The model worked while oil production outgrew population growth, making oil rent per capita ever-growing, until the industry was nationalized and oil prices crashed after a massive boom. In my opinion, Pérez Alfonzo’s Pentagono backfired.

PDVSA became so important that it transformed into a state within the state, and many years later, Chávez would make it into a parallel state.

The reasonable participation made it possible for the government to unilaterally increase income tax exclusively on oil companies until the government take took up almost 90% of the revenue from each barrel, right before the nationalization. Foreign companies stopped trusting the government, putting a hold on investments, slicing production levels by more than 1 MMbd within one decade.

Not only did the no more concessions slogan sponsor a massive expropriation process of national and foreign investments (called “nationalization”), it also put a full stop on exploration operations, which is why reserves stopped growing and people thought we’d run out of oil reserves in 20 years.

The creation of the first state-owned oil company CVP eventually led to the birth of PDVSA. PDVSA became so important that it transformed into a state within the state, and many years later, Chávez would make it into a parallel state.

The leadership in OPEC was progressively lost. When OPEC was created, Venezuela ranked among the world’s top 5 producers. But as production decayed, so did its leadership within the organization. While Venezuela pushed its production down, the Middle East pumped it up and soon took over the lead of the organization.

Furthermore, the long-time appreciated exchange rate hindered the productive sector because it was always easier and cheaper to import foreign products. Some industrialization did occur, but only under protectionist policies that in the end failed to create a competitive enough environment. National industries started to depend on preferential credit lines from the government, preferential exchange rates, protection taxes, and in some cases, direct capital investments from the national government, once again dependent on oil rent.

The whole scheme was designed during a period in which prices were either stable or rising, so for a moment it all seemed possible. But the honeymoon was abruptly interrupted by the 1980’s price depression and that’s when it all went to hell because the original input of the model, the international oil rent, was significantly reduced.

The model only works when the combination (Oil production)x(Oil prices) goes up and outgrows population increase. If this pattern cannot be kept, the growth becomes unsustainable since you’re not able to withstand the oil income per capita ratio.

But as the image shows, during the 1980’s both production and prices went down, stressing the country’s hard currency cash-flow for almost a decade. The situation was deteriorated furthermore by the overwhelming dollar-denominated debt payments due –does it sound familiar?

Thus, poverty became an epidemic in Venezuela. Poverty went from 12% in 1980 to 63% in 1989, and kept growing during the 90s, surpassing levels of 80%. The reason is because it was politically impossible to accept oil rent was not enough and that other sectors of the economy had to be activated, and that the distribution mechanisms for oil rent had to be reviewed. For example, is it worth having free public universities when hospitals have no supplies? It’s like we never realized money became a limited resource and trade-offs had to be made.

The illusion was repeated, coincidentally, during a large period of Chavez’s government. While international oil prices reached historical highs, Venezuela’s GDP grew 304% in the 2003-2012 period and everyone thought that it would all be alright again.

Now, oil prices have gone down, as well as production, and we are back in the same place we were in the 80s.

Looking towards the future:

For over 40 years we have been so focused on what to do with the oil rent that we haven’t realized the oil industry, as lucrative as it is, is insufficient to bear the weight of an entire economy. We, as a society, keep trying to preserve our own rent-seeking mechanism instead of paying attention to how sustainable the whole scheme is.

We should be asking questions like: should the government continue to control oil investments? What kind of public services are a priority? What are we doing to mitigate and adapt to climate change? What other sectors of the economy have potential for growth in Venezuela?

Recently, Deputy Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia announced that the country has started to deploy a strategy to move the country’s economy away from oil, in preparations for the post-oil era. Not a single word was heard from Venezuelan leaders, government or opposition, on this matter, or on what Venezuela should do to bring its long-term planning up to date.

It has become urgent that Venezuelan policy makers start to think and speak about these issues with the public in order to redirect the economy into a more sustainable path. Otherwise, we will keep leading the way of undeveloping countries, until we make the list of Least Developed World.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate