I found the average Venezuelan

(Today at Plan Pais I was honored to have been asked to moderate a panel composed of Asdrubal Aguiar, Carlos Blanco, Miriam Kornblith, Juan Maragall, and Ricardo Villasmil. The topic was on the search for a new narrative for Venezuela. This is a translated version of my opening remarks – specially dedicated to Edanis, wherever you are.)

(Today at Plan Pais I was honored to have been asked to moderate a panel composed of Asdrubal Aguiar, Carlos Blanco, Miriam Kornblith, Juan Maragall, and Ricardo Villasmil. The topic was on the search for a new narrative for Venezuela. This is a translated version of my opening remarks – specially dedicated to Edanis, wherever you are.)

Great narratives allow you to weave the fabric that connects human beings to each other. When you read, for example, Anna Karenina – to me the greatest of all narratives – you are connected to the characters, to Tolstoi, and to the millions of people who have been touched by the novel.

Doña Barbara is our Anna Karenina. Yet as much as we like to ponder and quote it, can we really say that it serves as the great Venezuelan narrative for the XXIst Century? Instead, how can we build a new narrative, one that can help us re-connect as Venezuelans and speak to our common human condition?

Can we find what we have in common with the average Venezuelan and, perhaps, build a narrative based on that?

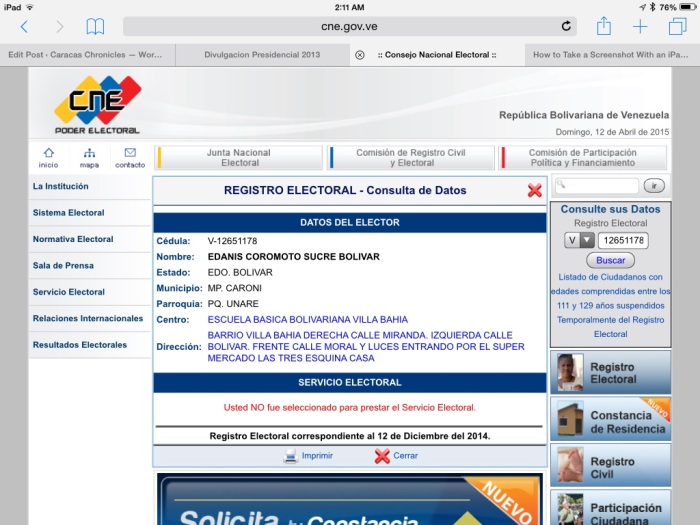

Well, I’m not one for much abstract thinking, so I decided to go in search of the average Venezuelan. And I did so by doing something which some of us who work in front of computers do from time to time: fiddle around with the CNE database.

I decided to find the voter with the highest cedula number in the registry – after repeated tries, I found that number was 25.302.256.

I then divided that number by two and I decided that this would be the average Venezuelan: a person with cedula number 12.651.178, a lady by the name of Edanis Coromoto Sucre Bolivar.

I nearly fell out of my seat when I saw the name: Edanis. Coromoto. Sucre. Bolivar.

It doesn’t get more typical than that. I knew she was the one – she is the average Venezuelan.

After recovering from what I thought was a sign from God, I began wondering about Edanis.

She votes in Unare, a working class suburb of Puerto Ordaz, close to the steel mills that the government set up in southeastern Venezuela with the faint hope of diversifying our economy.

The steel mills are now, for the most part, semi-working ruins. Edanis is probably in her late thirties. She probably witnessed the good times, and has seen the slow death of the industry.

She is probably lower-middle class, with a family, probably chavista (her voting center went for Maduro 66-33 %), but likely disappointed by now. She probably fears for her kids’ safety. She surely has to wait in line to find basic staples, possibly one or more salaries away from poverty. I can see her muttering, “esto con Chavez no pasaba.”

What do I have in common with Edanis Coromoto Sucre Bolivar? What do you? How can we weave a narrative that says something to both her and me?

That is the challenge of our times.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate