How the Revolution Ate the Joropo-Playing Japanese Students

A special investigation by Kanako Noda.

This post is available in Japanese here. 日本語でも読めます。

Este artículo está disponible en español aquí.

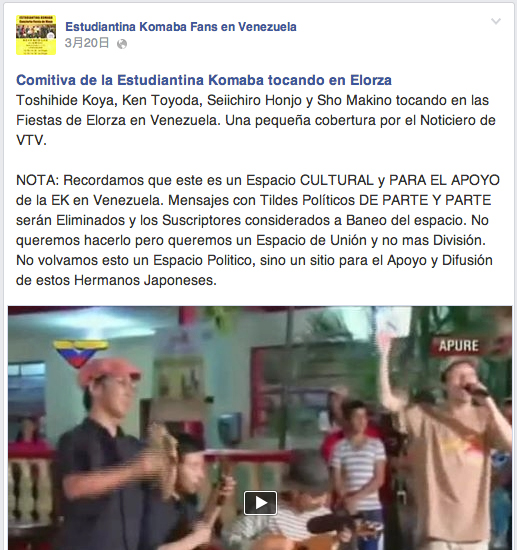

The four Japanese students look hot and excited as they clutch their instruments and break into a rendition of “Fiesta en Elorza.” Their performance is accompanied by children dancing in colorful costumes. They’re in Elorza, playing at the “Fiestas Turísticas Elorza 2014 Dedicadas al Comandante Eterno Hugo Chávez,” organized by the Ministry of Tourism.

The students are members of Estudiantina Komaba, the all-Japanese group that plays traditional Venezuelan music. You may remember them from a couple of posts on this blog from 2012. Their version of Alma Llanera went viral back then. And here they were, playing in Apure State this March, amid the biggest student revolt in Venezuela’s recent history.

The music is lovely. And the little dancers are too cute!

After the song, it’s time for their live VTV interview.

“¿Por qué la música venezolana?” The journalist in a llanero cowboy hat asks.

Ken Toyoda changes the subject and started to introduce the members, talking about their experience in Venezuela. Sho Makino, on the other hand, comments passionately “Venezuelan music is beautiful. I want more young people and kids to know about Venezuelan music”.

Watching this, my heart started to beat faster, and I felt ever more uneasy and confused. It was March 19th.

One month earlier, Bassil Da Costa had been gunned down in downtown Caracas. The student protest movement was at its height. People were being tear-gassed, rounded up, arrested, and tortured every single day.

Just weeks earlier, the Japanese embassy had cancelled some of the events and concerts that had been planned for the “Semana Cultural del Japón en Caracas” due to the instability.

And amid all this, here were four University of Tokyo kids playing on Venezolana de Televisión!

I was…confused.

You have to understand, the University of Tokyo – known as Todai – is not just any University. In Japan’s famously hierarchical society, Todai is unquestionably the top of the heap. Only the very best students can go there, and only after passing a brutal admissions exam. Todai is the puerta grande to the Japanese elite: its graduates float effortlessly to top jobs in Japan’s top companies or into the foreign service and the highest echelons of Japan’s highly prestigious state bureaucracy. These weren’t, and aren’t just any kids. These are supposed to be Japan’s best and brightest.

So why would four Todai students be singing in honor of the Eternal Comandante Hugo Chavez, live on Venezolana de Televisión, Venezuela’s flagship state propaganda network? Why was the singer wearing a Chavez T-shirt? What on earth were they doing at FitVen?!

Were they doctrinaire chavistas trying to give the government a helping hand, or were they just “useful idiots”, ingenues easily manipulated by a government with propaganda needs they could not understand?

That’s when my investigation started.

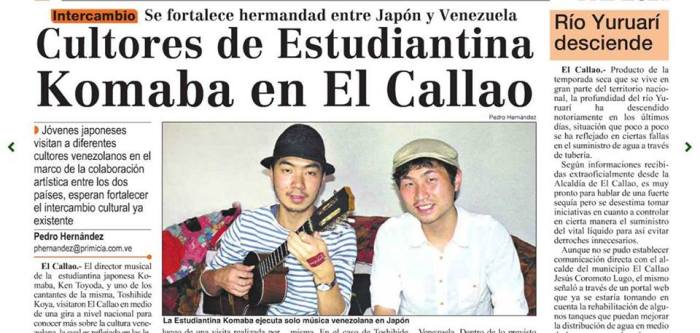

On March 1st, Ken Toyoda, (who plays cuatro, bandola, and guitar) and Toshihide Koya (vocals and cuatro) boarded their planes at Narita airport, just outside Tokyo. Both about to graduate from the University of Tokyo: Toyoda from the Arts and Science faculty, and Koya from the Law School.

Although thousands of anti-government protesters marched in Caracas on 2nd March, many Venezuelans still went to the beach to enjoy their holiday. And the two Japanese students were also heading to a carnival, Carnaval de El Callao, South Eastern Venezuela’s most famous mardi gras celebration.

Koya and Toyoda arrived on March 3rd to jam with Family Ground, a local Calypso group. They sang with them, played the Cuatro and the drums with them. They even painted their face black for the Carnaval.

The Japanese students received a rapturous welcome everywhere they went. It’s quite unique and exotic for many Venezuelans to see these “chinos de Japón”, who turned out to be masters of this very Venezuelan music.

“It was amazing experience”, said Koya, excitedly, when I asked him in a Skype interview how he saw the actual situation in Venezuela.

“You know, it’s always dangerous, because it is Venezuela,” Koya told me. “But, I can tell you, there was no such war situation during all my stay in Venezuela.”

On March 15th, two more members of Estudiantina Komaba, Sho Makino (maracas), and Seiichiro Honjo (cuatro), both ex-students from Todai, arrived in Maiquetía to join Toyoda and Koya. Makino currently works at Komatsu and also a member of Fundación Música de Maestros in Bolivia, while Honjo is a lecturer at Faculty of Business Administration at Hosei University, specializing in communications.

The two joined Toyoda and Koya and all four took the long, jolting bus ride to Elorza alongside a number of Venezuelan musicians.

The Elorza Festival got going on Wednesday, March 19th.

That afternoon, dozens of architecture students at UCV were attacked by collectivos. While these students were being physically and psycologically traumatized, Estudiantina Komaba members were playing live on State Television.

Estudiantina Komaba have repeatedly described their work as apolitical, and their musicians think of themselves as sharing an innocent passion for Venezuelan folk culture, but anyone can see that the Fiesta de Elorza was in no way innocent or apolitical.

Publicized by the government under the banner of #FiestaEnElorzaPorChavez, the folk music as well as the festival itself are heavily politicized. An image of Chavez is baked right into the festival logo. It is for Chávez, and addresses itself exclusively to people who followed Chavez. Even the folk music got expropriated.

You see why the timing of their “cultural exchange” strikes me as so wrong? How could these elite students have been so blind?

Maybe it has something to do with Estudiantina Komaba’s leadership.

Back in February, the founder of Estudiantina Komaba, Mr. Ishibashi, an associate professor of the University of Tokyo, had taken on the role of “expert commentator” seeking to explain the chaos in Venezuela to Japanese people. Mr. Ishibashi even studied at UCV in 2004, and is an expert on Afro-Venezuelan culture.

According to him, the images and sensational information that portrayed a “civil-war like situation”, “paramilitary bikers supported by the government are shooting the protesters” or “students are arrested and badly tortured” were all lies; media concoctions cooked up in information war labs.

Here’s his take on the situation on 23rd February,

“I think you are receiving more and more messages from Venezuelan people about the current disturbance. However, those who are taking troubles to send the sensational videos or images about Venezuela are probably committed too much to politics, irrational or irresponsible. I strongly recommend you to ignore them thoroughly.”

And he appealed to his followers asking:

“Your close Venezuelan friends say “SOS”? Wait a minute, where do they live? In Miami? Toronto? London? Mexico City? Paris? It’s possible that they got the information from the Internet like you. You say they live in Venezuela. Ok, but do they speak Spanish? Aren’t they sharing the information they can get in Japanese among Japanese community? Do you really believe that people who usually don’t take subway nor metro can grasp current Venezuelan situation?”

To be clear, Mr. Ishibashi is entitled to his own political views. It is his right to personally support Venezuela’s experiment in socialist dictatorship. It’s his right to deny the Human Rights Watch report on torture because, in his view, HRW is a NGO which is in conflict with Venezuelan government and in the past they gained a reputation for being politicized.

What’s troubling is that even as he echoes the government’s propaganda line, Mr. Ishibashi nonetheless insists on characterizing his position, and Estudiantina Komaba’s, as scrupulously apolitical. Worse, his mischaracterization of Venezuelan situation could have put his students in serious danger in a volatile situation in a country they just didn’t understand.

In fact, on 20th March, the Japan Ministry of Foreign Affairs updated the travel advice about Venezuela from caution alert to travel warning, officially telling Japanese nationals to avoid visiting Venezuela. And the Ministry has been advising not to take part in any political activities for security reason even before the update.

That day, Mr. Ishibashi tweeted, proudly but nonchalantly, that Estudiantina Komaba’s performance was also reported by Ultimas Noticias.

After the appearance in Elorza on VTV, chavista interest in EK seemed to balloon. Soon they were doing recordings at VTV and ViVe, and started being featured more and more heavily on other pro-government media.

I don’t doubt that some Venezuelans were thrilled with their sudden stardom. However, I imagine that not all Venezuelans appreciated their performances made in the context of heavy-handed Bolivarian revolutionary propaganda. And actually, Estudiantina Komaba rushed to tweet plausible excuses;

“Hemos representado muchas veces la cultura Venezolana en Japón, sin o con la presencia de la Embajada de Venezuela en Japón,” adding, “Nuestra actividad es apolítica. Aparecemos en VTV, Globovisión, C del Orinoco, U Noticias, El Nacional, BBC, CNN sin barreras“.

In his Skype interview with me after his return to Japan, Toshihide Koya, the singer, acknowledged that they received some negative comments from some in the audience saying that they were disappointed to find Estudiantina Komaba supporting the government.

“Whatever they may say, we are apolitical and only devoted to cultural activities. We don’t touch politics at all. You could have, individually and personally, certain political idea but it’d never be as a group. Estudiantina Komaba is apolitical.”

On the 21st, Toyoda, Makino, Koya and Honjo returned to Caracas from the Llanos to conclude their Venezuelan tour. They had a lot of concerts and interviews lined up in Caracas. After the sensation of Fiesta en Elorza, people rushed to them to take photos and to cheer them at bus stations. It was as though they’d become local pop stars.

So, on the 22nd of March, EK members were likely busy for their concert. Perhaps that’s why they missed the enormous march in Caracas that day.

Some could wonder how it could be possible for them not to see a march that big. What’s alarming is that it may well be true that they had no idea: given the heavy pressure on local media not to cover the protest, it seems possible that people hanging out with government handlers, exposed only to government media, and under the leadership of people telling them that these protests were a few fanatical neoliberals of little importance could have been in Caracas that day and simply missed the tens of thousands on the streets. After all, EK appears to have moved around entirely inside the pro-government media bubble.

In the morning of March the 24th, Estudiantina Komaba continued its tour at the CANTV Auditorium, doing another live broadcast for the “Contrastes” programme on VTV. This event is entitled “Homage to the Comandante, delighting the audience with the best parts of traditional Venezuelan music, as a tribute to eternal giant Hugo Chavez”.

Makino posted emotionally on Facebook after the CANTV concert.

“I’ve never dreamed that we would receive such a welcome. Applause for the music and the endless cheer after the performance. I realized once again the cultural meaning of EK activities, and I’m newly confident in the mission in the future. I want to share this deep emotion with more and more Venezuelans. It was a wonderful experience and I will never forget it”.

VTV got some very nice pics at that concert, to boot:

It’s easy to see what VTV wanted from Estudiantina Komaba. This is the Venezuela-Japan cultural exchange Maduro wanted despite EK’s intention.

Even more carelessly, at that moment, the EK fan site on Facebook had a cover image with the four in Chavez T-shirt in front of Chavez mural.

At the same time, the webmaster of Estudiantina Komaba’s Facebook fan site was busy erasing the political comments and warning people not to write any comment that touched political matters in any way.

The irony of this happening because EK was being charged with supporting, among other things, a state actively engaged in censorship, seemed lost on them. In EK’s view, since their activity is apolitical, all political comments had to be censored from their Facebook page.

Estudiantina Komaba held the final concert of its tour on the 26th of March.

This last one was more actively promoted than any of the previous ones. It was a part of Maduro’s project, Concierto de Paz. Mintur cheerfully broadcasted a commercial for the upcoming concert. Andrés Izarra, the Minister of Tourism himself, promoted this “Concert for Peace”.

Perhaps sensing that the Japanese musicos were a big hit with the VTV audience, Izarra took the chance to climb up on stage and even give a speech to them. Just check out how apolitical their participation really was:

In this video the musician William Alvarado explains that the world wide (which means in Japan) success of Venezuelan folk music is derived from the glory of the Comandante. “Venezuela is the eye of the hurricane thanks to Comandante Chavez and the audience of teleSUR, which is growing all over the world.”

In my interview with Koya, he seemed to have had no idea who Andrés Izarra was, or what he had done before becoming Tourism Minister. To him, Izarra was just another local official, nothing to distinguish them from the other dignitaries who had showed them around. At no point did they seem to grasp that they were dealing with the designer and original implementer of chavismo’s state propaganda system, or that their music was being systematically used for propaganda purposes.

And Koya defended their media profile, saying “we did not choose exclusively the pro-government media. Unfortunately only pro-government media are interested in our activity.”

It never seems to have occurred to him that this could have something to do with the fact that independent media were so busy covering the historic outbreak of mass protests shaking the entire country that covering some joropo-playing Japanese kids was not a priority just then.

For a brief time in March, to someone relying only on state media, the four “chinos de Japón” from Estudiantina Komaba were a kind of national music sensation. It’s obvious that the pro-government media had good reason to promote their activity. What’s troubling is that such elite students from Japan’s top university never seemed to have asked themselves what that reason was.

As thousands of dissidents were being arrested, hundreds hurt and dozens killed, the state media apparatus was desperately looking for feel-good stories that kept the protests off official screens while giving a sensation of international acceptance. EK was perfect for them.

Koya, Toyoda, Makino and Honjo will go back to Japan always have colourful stories to share about their South American adventures back in their youth. Even today they don’t understand, and they will probably never accept, the role they played in entrenching Latin America’s newest dictatorship.

Kanako Noda translates selected Caracas Chronicles posts into Japanese. She is married to the founder of this blog.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate