Curious in Bogotá

As you may remember, I (Anabella) decided to bid on Sicad II the same day that I handed in my Cadivi folders. The trámite was due to my need to go to Bogotá for my sister’s wedding.

As you may remember, I (Anabella) decided to bid on Sicad II the same day that I handed in my Cadivi folders. The trámite was due to my need to go to Bogotá for my sister’s wedding.

The second I put a foot in Colombia, I had the urge to register some of the anecdotes of what we Venezuelans go through when we travel abroad.

The first one: I went through immigration in Bogotá at 7:45am on Friday May 9. According to my brother-in-law, Oscar De León got his luggage 3 minutes before me and I didn’t see him. Darn.

Cadivi: can’t live with it, but can’t travel without it.

(I should say Cencoex and not Cadivi, but let’s be honest: no one says Cencoex).

The relationship with Cadivi is love-hate. You get cheaper dollars (heart), but the whole situation is mighty annoying. As you probably know, there are some steps you must remember if you want to use your hard-earned money abroad.

On April 29 I got an SMS from Cadivi that said that my credit card was ready to go. But… would it work? As soon as I got to Bogotá and left my luggage at my sister’s place, I did the first thing that Venezuelans going abroad have to do: put my credit card to the test. I went to a nearby book store, picked up a couple of books, and then it was show time. I took a breath and handed out my credit card and passport. Ten seconds and thousands of heartbeats later, I heard the magical words: “sign here, please.” There has to be a word for the sigh of relief Venezuelans emit when their card goes through the first time.

Now, it’s not like you can rest easy and simply enjoy your vacation. Each time I paid with my credit card, I would make a mental note of how much I’d spent so far – Cadivi has a strict limit, and going over it carries huge fines and even getting kicked out of the system altogether. Make a math mistake and you may never be able to leave Venezuela again. Every time I would get back to my sister’s house, I’d check my online banking account. Even if the charges had not yet been registered in my credit card statement, my bank –Mercantil- would let me know my remaining quota. It sounds kind of excessive and picky, but I have friends that lost their Cadivi rights for a year because they had surpassed their consumption limits and I’d be really irritated if that happen to me.

As much as you want to leave the Revolution behind on your vacation, it’s always with you.

The situation is even worse due to ignorance about the exchange rate. When you travel to countries that use a currency other than the U.S. dollar the situation becomes even more tedious because your limit is set in dollars, and in Colombia, well, prices are not in dollars. You must find out the exchange rate and play with estimates. When I arrived in Bogotá I could get 1,980 Colombian Pesos for every dollar, so I would assume an exchange rate of 1,950 just to be on the safe side.

Suppose your card works fine and you don’t go over your quota. This does not mean you are home free. As soon as you come home, you have forty five days to present a sworn statement of how many single charges you made on your credit card, the total amount charged, and if you actually withdrew your approved Cadivi cash quota. And the vouchers… let’s not forget the vouchers. Those little pieces of papers –and their accompanying receipt- that should be kept for up to 18 months in case Cadivi asks you to present them as proof of the “correct use of foreign currency”- are a must. You lose the little slips, and you may be toast.

Supermarket fun.

A trip to the supermarket has become an attraction all on its own. You can always tell the Venezuelans traveling abroad – they’re usually the ones standing in the toilet paper aisle, with a look of shock and awe in their faces.

On my first night in Bogotá I made a quick trip to the supermarket.There was no line and it had everything. You could buy 10 Harinas PAN or 20 cartons of milk if you wanted to – imagine that. While I was paying I remembered that the first time I took pictures inside a supermarket was actually in Bogotá, back in November 2009. At that time supermarket photos were just starting to become popular. Now they seem to be more common than pictures with Mickey Mouse.

A couple of days later I visited a bigger supermarket. Once again, they had everything you might need. Passing through the soda aisle I saw a shopping cart with toilet paper, and the first thing that came to mind was: how many can I get? I stopped for a second and a sad chuckle came out of my mouth. I kept on walking and went to get some milk on aisle 10. While I was choosing a brand of skimmed milk I wondered: when we would see a fully stocked aisle of milk in Venezuela? Back in March, milk shortage surpassed 90%.

Very short scavenger hunt.

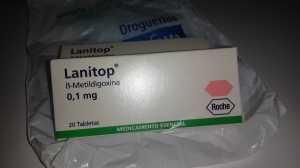

On the first day of my trip I found via Twitter that a friend needed “Digoxina 0,25mgr” for her father. I wrote her a DM and promised I would get her the medicine.

I still can’t believe so many medicines are impossible to find in Venezuela. The Central Bank of Venezuela reported medicine shortages of up to 50% in March, but the worst part is that the government doesn’t seem to be doing much about it. In February, 59 active pharmaceutical ingredients were missing from the shelves. By May, the number had gone up to 96.

To get my friend’s medicine, I had to visit 3 drug stores. This wasn’t because the medicine was unavailable, but because I was getting lost in translation. As it turned out I had to ask for Lanitop and not Digoxina (active ingredient) and it wasn’t until the third try that an actual pharmacist attended me.After that, it took me three minutes from “good afternoon” to “your receipt”.

To get my friend’s medicine, I had to visit 3 drug stores. This wasn’t because the medicine was unavailable, but because I was getting lost in translation. As it turned out I had to ask for Lanitop and not Digoxina (active ingredient) and it wasn’t until the third try that an actual pharmacist attended me.After that, it took me three minutes from “good afternoon” to “your receipt”.

FAQ.

Just as I signed the first credit card voucher of the trip, the cashier asked “are you planning to return to Venezuela?” My mother responded with a simple “of course. We are just visiting…” The cashier’s face turned into a mix of shock and pity. All I could say -with an honest smile- was “seguimos en la lucha”. This was the first of many questions I would get as soon as people knew I was from Venezuela. But the most common would be “that accent… Venezuelan?” and “things are pretty bad, right?”

It was impossible to escape Venezuela, as people were always asking me about it.

Other FAQs were:

Q: “Is he as dumb as he seems?” Yes, they were talking about the bird whisperer, Nico Maduro.

Q: “When will it [the crisis] be over? I really like Venezuela and want to be able to visit again”.

Q: “When are you leaving Venezuela? You should move here [Bogotá]”. #SufroComoSansa

Q: “You’ve had a death per day for a couple of months, right?”

A: It took a second till we realized that he was talking about the current guarimba situation. I answered “not really”. All I could think about is that 1 Venezuelan died every 37 minutes between January and April 2014.

Patria, patria, patria querida.

I arrived in Maiquetía airport on Tuesday May 20 at 12:55pm.

The Caracas-La Guaira highway was blocked by neighbors protesting the murder of a bus driver, so we took the Carretera Vieja (the experience deserves a post all on its own). When I got home 3 hours later, we had no running water.

Home sweet home. It seemed like I had never left.

(Thanks to @danielragua for the help and for some AWESOME gifs)

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate