The Dimmest Bulb

Today, we have a Guest-post from our occassional Mérida correspondent, Guido Núñez-Mujica:

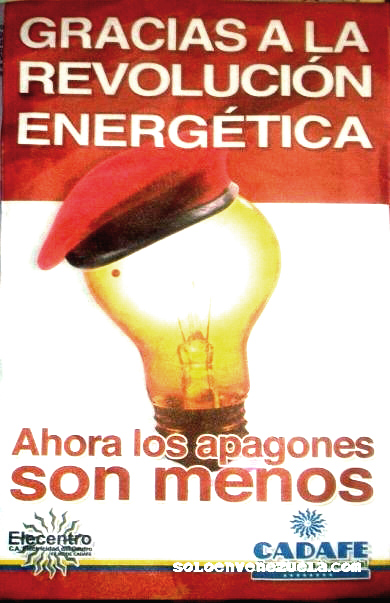

Bolivarian dim bulbs

In Caracas, it’s just about possible to ignore them. But out here in Mérida, the blackouts have insinuated themselves into the fabric of my daily life.

They control my schedule, send me to bed far earlier than I would ever contemplate otherwise, wreak havoc with my lunch time, spoil my food, damage my gadgets and drive my blood pressure way, way up.

They began in early September, when our nationalized utility CORPOELEC (or COPROELEC, as I like to call it), called them a temporary problem, saying the blackouts would last for 18 more days (ignoring the previous blackouts) and then things would be back to normal.

I was furious, about to go berserk, cursing the government and the airheads who manage the utility. Most of September with periodic blackouts? Intolerable! And yet, here we are. It’s 2010 and they’re only getting more frequent.

I am mad at myself. Like everybody else, I’ve gotten used to this crap. I keep candles and flashlights nearby, at home and at the biotech lab where I work. My lab coworkers and I keep silly board games handy to play as we wait out the customary 2 hours (or so) without power.

When the lights go out “only” once in a day or for “only” for an hour, I feel a surge of relief…and right away I feel disgusted at my own Stockholm Syndrome. I tell myself that I should be indignant, spitting nails, breathing fire over the lack of accountability of CORPOELEC’s faceless bureaucrats. Instead, I’m glad…and then, when the power goes out again a few hours later, I find myself taking a deep breath before using the light from my cel phone screen to find the flashlight and checking that the stoves, autoclave and coffee maker are turned off before leaving the lab and heading home.

Gone are the days when I shouted, got rabid and cried bloody murder. Now, all I have is resignation. There is nothing to do but endure the rain of crap. At most, I will raise my fist and shout “Así, así, así es que se gobierna” or “Viva la revolución energética” despondently, no matter if my Chavista coworkers are around or not.

Screw them.

Come to think of it, what pisses me off the most is not that we are passively suffering this (yet another symptom of our collective decay), or that a government that has been in power for 11 years, during one of the biggest oil booms in history, with tons of money, with the greatest amount of political power ever seen in our modern history has neglected our electricity grid to the point where blackouts are not only common, but expected.It’s not just that, in our lab, some devices have already failed and other really expensive ones are in peril. Nor is it that the autonomous power plants at my university are starting to fail, as they were designed for emergencies, not for continuous use.

The worse part, the thing that really drives me around the bend, is that the blackouts are basically random.

All that you know (and no thanks to CORPOELEC) is that you’ll have blackouts twice a day. And not even that is certain, some days you have three, others, blessedly, just the one. Beyond that, you can only guess when it’ll be. Sometimes, for a couple of weeks, you’ll lose power between 12:30 PM and 3:00 PM, and then, next day, when you’re least expecting it, you’ll get a blackout at 10:00 AM and another at 4:00 PM, next day at 11:00 and 3:00, and one of them lasts almost three hours.

This makes it impossible to plan, to take any precautions. You cannot take basic steps like unplugging sensitive devices ahead of a blackout, or postponing key experiments. The minimal courtesy – yes, courtesy – it would take for CORPOELEC to publish a schedule of the upcoming week’s blackouts in the newspaper each Monday is just beyond them. Blackouts just come and go at random, as the bureaucrats please.

One of the most frustrating experiences these days is going to banks. Most Venezuelans know what a hellish experience that is. You invariably have to wait for a long time in a crowded space, standing in line, until you reach the cashier, watching as people skip the line in front of you. Too often, you have no choice but to endure, at times outside, in the burning sun in front of your chosen bank branch, where the line snakes to, waiting, sweating, wasting your time, sacrificing it at the altar of the idiocy, stupidity, and intolerable service of what passes for the private sector in Venezuela these days.

Now, going to the bank is even worse, as a blackout could catch you before you finish your business there, and, sorry, buddy, you’re out of luck. Go to another branch (even more crowded than usual) or wait until tomorrow, if you can afford it.

You spill out of the branch exhausted only to be choked by exhaust from the power generators running on gasoline that many store owners have been forced to buy. But, for Juan Bimba (our national Joe Sixpack), that energetic sovereignty is out of reach. Yet again this revolution that is supposed to help the poor pisses on them while the rich can afford to ease its effects.

Due to the blackouts, public transportations for certain areas, usually the poorest sections of Mérida, is not operating at certain times, as crime has increased too due to the absence of street lights. Car-less people like me are screwed yet again, while again the middle class and the rich barely notice, sheltered by their resources.

Mérida has been very badly hit. Other places like Valera, where my family lives, have it a bit better. However, Caracas is still untouched to such an extent that measures to shut down malls after 9 p.m. outrage people. But in the West of the country, it’s apparently much worse than here, even, with blackouts that last 6-8 hours each day. Is it any wonder that Chavez’s popularity is falling?

The scale of the government, corruption, unaccountability, authoritarianism and inefficiency are starting to cause real social tension here. Last week neighbours of Las Américas Av. burned a CORPOELEC customer service center to the ground.

I cannot blame them, and probably if I had been there, I would have helped them to burn that symbol of disdain, callousness and stupidity. Government’s reaction to this was to use the Bolivarian National Guard against the buildings around CORPOELEC office, destroy their fences, fire tear gas canisters into their buildings and break down their doors.

The next day a mob, blaming the mayor, (who’s from an opposition party, and as dumb, inefficient and lame as any other mayor we’ve had) threw a Molotov cocktail at the mayor’s office. Part of the mob was bused in from nearby town, mere astroturfers. In the wake of all this, the government threw in jail and issued warrants to search the houses of several prominent local members of opposition parties.

It shows they’re rattled.

And how did Chavez’s party, the PSUV, react? Did they deplore the violence, but acknowledge that the people are angry and need their power problems solved, or at least a decent schedule that allows them to get organized? Did they take a page from the recently deceased and note that one cannot ask the pueblo to immolate itself for the revolution? Of course not.

They went out of their way to express solidarity with the very same company that is making our lives miserable, disturbing us and affecting us in many other ways besides power issues, their solidarity with CORPOELEC, while Juan Bimba, after a hard work day cannot get to his house after 9 because there are no more buses, while Mr. Bimba could not cash his meager paycheck, despite losing 2 hours in the bank, while these things happens, their solidarity is with the very same company that makes this possible.

And the ones that got mad and acted out their rage are not El Pueblo, but evil coup makers payed by the CIA and political parties, traitors, empire’s lackeys, while the people throwing Molotov cocktails at the mayor’s office and being bussed around with our taxes and oil revenues, that’s El Pueblo. Orwell would be proud.

Besides, as Tamara Pearson says, the opposition are the ones to blame for the blackouts.

If Mérida holds any hints as to the future of Venezuela, be prepared for really gloomy times, as the collapse of our infrastructure metastasizes through the country.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate