World Social Forum Files: The Housing Crisis

With the World Social Forum meeting due to be held in Caracas later this month, I figure at least some of the 80,000 kids planning to travel to Caracas for this shindig will be scurrying around the Internet looking for information on the revolution. My next few posts go to them, with the heartfelt hope that you’ll read them with an open mind. The piece below is an “oldie but a goodie” – written in June 2004, it tackles an issue that has, sadly, only become more relevant in the last few weeks. Keep it in mind as you travel that long, slow road from the airport up to Caracas.

No Magic Solutions for Venezuela’s Housing Crisis

One of the most interesting articles I’ve written about Venezuela grew out of a meeting with five privileged white men who had held positions of some prestige under the old regime. They harshly condemned Chavez’s performance and called for policy to take a radical new direction. They threw their hands up in frustration as they considered the government’s folly, shook their heads gravely as they described how they’d been excluded from the spheres of power, and generally despaired over their powerlessness to influence policy in the slightest.

Alemo

The five were members of Alemo, a think-tank dealing with Venezuela’s urban housing crisis. Professional architects and urban planners – most are professors at the Universidad Central de Venezuela – they have spent two decades in in-depth study of the challenges posed by Venezuela’s mushrooming shantytowns, known as barrios. With a bureaucrat’s fastidious concern for for detail, they have documented the problem, thought through the policy alternatives, costed the various possibilities, and published the lot. In their view, the rock-bottom, lowest-imaginable price-tag for bringing all of Venezuela’s urban dwellers to a basic standard of safety and comfort would come to a harsh $60 billion.

The price-tag is astronomical – over 60% of GDP, over twice the government’s global yearly spending. Even if, as Alemo urges, the cost is spread over 10 years, a $6 billion/year price tag would require quadrupling the country’s housing budget.

It’s hardly a surprise, since Alemo’s study just quantifies the disastrous housing shortage you can see in any Venezuelan city. One-third of the country’s housing stock consists of ranchos – shanties. However, fully half of all Venezuelans live in ranchos. Thousands of ranchos need to be bulldozed and replaced – they sit on geologically unstable ground, and could give way at the next rainstorm – while hundreds of thousands require investment to bring them up to minimal standards of safety and crowding. Moreover, hundreds of barrios need major investments to bring in basic urban amenities – from electricity and sanitation to schools, infermeries, playing fields and roads good enough for buses to use.

How did Alemo arrive at its $60 billion figure? The process was long and involved, but the innitial question was simple enough: what would it take to build a Venezuela where everyone who lives in a city has access to basic urban services, nobody lives at very high-risk areas for flooding or mudslides, nobody lives in extremely crowded or dangerously deteriorated housing, and the housing stock grows quickly enough to absorb the new families looking for places of their own as they hit their 20s?

To keep costs more or less reasonable, Alemo applied deep cost-cutting measures in their calculation, including a radical plan for the state to construct “proto-houses” (with all services, but minimal construction area) that residents would subsequently expand and complete, as well as financing mechanisms that would split costs between the state and beneficiary families. So the $6 billion/year tag is a rock-bottom figure, the very least the state could spend and still hope to meet its goals. Spend much less than that, and the problem deepens rather than receding.

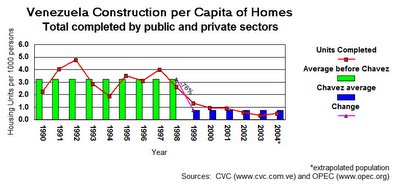

“Normally,” I remember them telling me, “you’d need to build at least 100,000 new low-income houses a year – not to reduce current levels of crowding, but just to keep up with population growth – just to stay even. To start to make some headway against the truly appalling level of crowding in some ranchos, you’d be talking about 120,000 houses a year, at least. Since the start of the Chavez era, we’ve never seen more than 60,000 houses a year. So, in effect, we’re going backwards: every house that you come up short from that 100,000 target means another family forced to choose between squatting on an empty plot of land and building a rancho with their hands, or staying put and living in increasingly intolerable crowding with their relatives.”

Serious Planning

Of course, this is just one area of concern: expert NGOs could (and have) come up with similar analyses for hospitals, schools, social security, the fire-fighters, the police, prisons, essentially any part of Venezuela’s huge, overbloated but underfunded state. Alemo’s approach is based on a long, hard, careful, uncompromising look at the policy problem followed by specific proposals for budgeted, thought-through solutions. These are soft-hearts and hard-heads at work – their conviction is that the more urgent a human problem is, the more down-to-earth and meticulous the planning for a solution should be. You can call their outlook technocratic if you want, but in my book Alemo’s outlook represent a hard-bitten marriage of idealism and pragmatism that eschews magical solutions and urges the state to tackle these matters with eyes wide open.

Now, how has the Chavez administration responded to Alemo’s calls? The answer goes a long ways towards explaining my despair about the government. First, the chavistas purged Alemo members from all state institutions dealing with urban housing – putting the state’s housing bureaucracy in the hands of doctrinaire chavistas that would neither produce independent estimates nor raise troubling questions. Then, it set out to confuse the issue, making oversized claims for its decidedly undersized achievements.

At no point since 1999 has Venezuela come anywhere near to building the 100,000 low income housing units per year that it would take to keep up with population growth, let alone make headway into the housing crisis. Yet the government, conscious that very few people know this, continues to obfuscate, touting its house-building totals – just 25,000 units in 2003 – as major revolutionary triumphs! Stop and think about what this means: 25,000 new houses built means 75,000 poor Venezuelan families were forced to either build themselves a shanty or stay on in impossibly cramped quarters…and the revolutionary people’s government brags about this as a success.

What’s the purpose of this detour into the minutiae of the Venezuelan low-income housing crisis?

Government supporters tend to start from the assumption that the only reason anyone might oppose Chavez is class self-interest. What’s most irksome about Chavez to many of us, however, is the magical strain in his government’s thinking: its blanket rejection of any kind of independent advice, criticism, or debate, and its outright disdain for specialist know-how and hard-knuckled planning. Its dogmatism, its deep suspition about the motives of critics, locks the government into stances that not only cannot solve the problems at hand, but, even worse, close down the spaces for genuine debate about them, banishing people like Alemo to the ranks of counter-revolutionary elements.

The results is a politics of social inclusion that remains confined to the rhetorical realm – Chavez’s discourse certainly makes his constituents feel included – while deepening the country’s social problems. Point out that Chavez’s housing policy will force 50,000 families to squat and build shanties next year and you’re condemned as a Bush-collaborator, an escualido fifth column that needs to be purged from the state.

It’s hard to overstate the chilling effect the resulting climate of intimidation has on free and open debate, on honest deliberations of the country’s problems. If you know the truth and the truth doesn’t fit the party line, you learn to keep quiet just to protect yourself. Debate on a matter as seemingly apolitical as housing becomes deeply politicized, and those who question the government’s policy are dismissed as CIA agents or coup-plotters before their criticisms are even considered.

This “management style” consistently rewards ideological conformity and magical solutions over serious planning. In such an environment, pleasing fictions are always preferable to uncomfortable facts.

So long as criticism is seen as prima facie evidence of treason, so long as critics’ voices are ignored as a matter of principle, so long as the worst of motives are automatically ascribed to all who dissent, the government will continue to make policy inside an ideological bubble where loyalty counts for far more than serious planning. Instead of no-nonsense social policy, instead of budgeted estimates and effective projects, instead of serious plans aimed solving longstanding problems, we’ll continue to get what we’ve been getting: ad hoc measures aimed at short-term political advantaged and divorced from any kind of serious analysis of what needs to be done in the long term.

Or, to say it in a single word, populism.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate