Oddly fun...

I must have been in a very odd mood last night. I spent over an hour listening to this speech Chavez gave on December 5th, 1999 (Real audio stream). It’s an eye-opener.

The first half an hour is an impassioned defense, an apology even (in the Greek sense) of the February 1992 “military rebellion” Chavez led. He carefully explains that February 4th was a military rebellion not a coup – the difference apparently being that a rebellion is when Chavez is on the giving end, a coup when he’s on the receiving end.

He waxes lyrical about the feverish, even obsessive (Chavez dixit) efforts the conspirators made from 1989 to 1992 to plan the coup and “accelerate what needed to be accelerated.” Extra schadenfreude comes our way around minute 14, when he “honors” his fellow conspirators one by one, stopping to say a few kind words about each…Francisco Arias Cardenas, Jesus Urdaneta, Acosta Chirinos, any number of people who’ve since switched sides. “True patriots!” he calls them, then adds “it honors me and commits me even more to the cause to share a stage with them!” He also saves some flattery for Kleber Alcala and Felipe Acosta Carles, brother of Luis, who apparently died in the riots of February 1989.

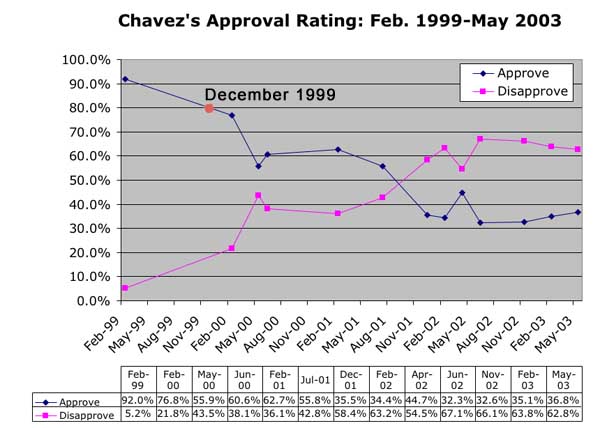

The speech then descends into a torrent of praise for the new constitution – which was voted on ten days later – and eventually widens into a veritable flood of abuse hurled at the opposition. This is curious. Remember, it was December ’99. Chavez had an 80% approval rating – the opposition was in no way a threat to him, or even a serious political force to contend with. It was mostly a rump, really, with neither a real following nor real power. That doesn’t dissuade Chavez from spending half the speech attacking them, villifying them in aggressive and willfully provocative terms. I say “willfully” for a reason, Chavez makes it clear he knows exactly what he’s doing. “Para que mas les duela,” (“so it stings more,”) he says, just before launching into one of his more colorful attacks.

Chavez’s 1999 Approval Ratings: Those were the days!

I admit I was a bit disappointed with the speech, in that I was hoping to hear more about popular sovereignty and then blog about the way the phrase has disappeared from the official lingo.

What I found was something a bit different – a demagogue who uses his astonishing rhetorical ability to paint a highly simplified, Manichaean view of the world. Chavista rhetoric inevitably dissolves into a Disney style moral universe where those who follow him are good, really good, inherently good and virtuous as revealed by the very fact that they follow him, and those who oppose him are deeply, fundamentally evil, as revealed by their opposition to the revolution. Hammering in this point seems to be the point of the speech.

It’s easy to forget, but thanks to the internet, easy also to remind ourselves. The class-warfare rhetoric, the divisionism, the hate-mongering, the conscious effort to intensify class antagonism, all of that has been there from the start. It was even there when Chavez had no effective opposition, two and a half years before April 2002, when there were no marches, no signatures, no cacerolazos, no National Assembly, no one really to challenge his power.

To be a chavista, to my mind, is to accept this moral universe, to wallow in the dumbed down certainties of an ideological orthodoxy that demands your total acritical loyalty and counts anyone who raises a critical voice as an enemy.

Seen in this way, polarization is not the accidental by-product of Chavez’s rule. As Chavez obliquely hinted in his letter to Carlos in his parisian jail, polarizing society along class lines has been the chavista plan all along. It’s been pursued with the bloodymindedness of a true believer and the skill of a born demagogue. And as I try to work out the implications of that strategy, I do get the feeling that a diet of geraniums is particularly ill-suited to combating it.

So listening to that 5 year old speech left me quite pessimistic about the possibilities of building a dialogue across ideological lines. Long before the “positive feedback loop” that Sabatier writes about had taken hold, Chavez’s strategy was already founded on the old leninist maxim of “deepening the contradictions.” The worse it gets, the better it gets. Even all those years ago, enshrining the positive feedback loop of polarization was the cornerstone of government policy. So how the hell do you get around that?

I have no idea, but the speech did leave me with one (semi-)conforting thought: it’s the comecandelas who are playing into Chavez’s hands. Chavez relies on polarization, but it takes two to positive feedback loop!

Chavez’s political program makes no sense outside a context of systemic polarization. In a sense, Chavez is polarization. So if you want to fight Chavez, fight polarization!

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate