How did Venezuela get so unstable?

Time to step back from the political play-by-play – in this post, I want to explain to a broader audience how on earth Venezuela got into such a huge mess in the first place. I realize how baffling our political crisis must seem to an outsider. Here’s a conceptual primer.

It seems like it’s been much longer, but the political crisis in Venezuela has been going on for 27 months. It all started with the approval of 49 new laws by presidential decree on November 13th, 2001 – more than two and a half years after Hugo Chavez took office. The crisis has waxed and waned since, but it has never gone away.

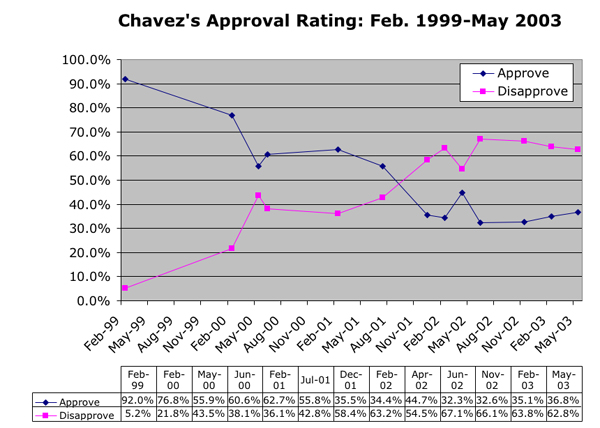

Until mid-2001, Chavez had basked in stratospheric approval ratings, and his dominance over the country’s politics had been total. For a number of reasons, those poll numbers started to drop at the beginning of 2001. Within months, what had been an 80%-20% country had turned into a 40%-60% country, with a majority opposing Chavez for the first time.

That’s the first thing to bare in mind: the political crisis only really started after this turn around in the polls.

Source: Datanalisis. Question wording: “how do you evaluate the work of President Hugo Chavez for the welfare of the country?” Sample size: 1,000. Interviews conducted generally at respondents’ homes.

Chavez’s honeymoon was long and eventful. In those first two and a half years in power, he completely reshaped the Venezuelan political landscape. He commissioned a new constitution, packed the supreme court with cronies, changed the country’s official name, packed the prosecution service with cronies, crushed the old political class into irrelevance, packed the electoral council with cronies, declared himself leader of a revolution, packed the public administration with cronies and made generals sell discount vegetables to the poor. Through it all, he basked in the people’s genuine adulation for it.

49 laws

After pushing through his radical political reforms and being re-elected with 60% of the vote in 2000, Chavez moved on to his substantive agenda. In November 2000 he used his two-thirds majority to get the National Assembly to grant him special powers to legislate by decree. For twelve months, the president had carte blanche to change any law he wanted in any way he wanted. It was pretty extraordinary, but in the zero-opposition atmosphere before the turn around in the polls, he got away with it.

The way Chavez handled this unique opportunity says much about his core ideology, and created the political crisis the country is still wading through today. Instead of consulting with stakeholders, as had been the tradition in Venezuela, Chavez drafted the new legislation behind closed doors, with no public consultation. In fact, most of the 49 laws he decreed were presented as a fait accompli on November 13th, 2001 – the very last day of his special powers period.

There was no public debate, no public scrutiny, no chance to influence policy at all.

Now, contrary to how it has sometimes been presented, for the most part the new laws were not all that radical. Some, like the Lands’ Law, were bound to be controversial, but many others were quite innocuous. They were markedly statist in many places, yes, and cumbersome and unrealistic in many others, but really the fight that developed was much more about process than content.

What really alarmed the opposition was the president’s strident unilateralism, his angry refusal to even talk about the reforms with evident stakeholders before enacting them into law.

Take commercial fishermen, just as an example. The new Fisheries Law Chavez decreed radically changed the ground rules in their industry. It limited the range of waters they’re allowed to fish, so it evidently affected them, and negatively. But since they were never consulted about it, none of their quite legitimate concerns could be taken into consideration. The Chavez law had no provisions at all to soften the blow, no phase in period, no investment tax breaks to help meet the regulations, no technical assistance to help the fishermen comply, nothing. None of the mechanisms the fishermen might have bargained for were in the law simply because the government refused, as a matter of principle, to bargain with them.

Worse still, when the fishermen protested, the government denounced them as counterrevolutionary elements and enemies of the people. This cemented the growing perception that the government was not just indifferent to them, but actively hostile.

The irony is that the Fisheries’ Law is arguably quite a good, forward-looking piece of environmental legislation. By refusing to even try to build a consensus around the new rules and instead antagonizing the stakeholders, Chavez undermines the possiblity that it will ever be implemented properly.

It’s the sectarianism, stupid

It’s easy to forget that, back in late 2001, all the opposition movement was really asking for was for the government to “correct course.” We demanded space for dialogue, for a formal channel of communication with the government and some chance to scrutinize and comment on policy proposals before they were enacted into law. “Rectification” was the word on everyone’s lips. It was Chavez’s strident refusal to legislate inclusively that led to the very first one-day general strike, on Dec. 10th, 2001 – and even then, what the strikers demanded was for the government to sit down and discuss the new laws, nothing more.

Again and again, Chavez responded with bluster and scorn. He demonized those who complained about our exclusion, often substituting ad hominem attacks and vicious broadsides for political argument. He made it clear to us that the revolutionary state was there to disenfranchise us, to free the political arena from the pernicious influence of counterrevolutionary thinking.

This was especially ironic given that Chavez’s early political rhetoric was predicated around a single word: participation. Throughout 1998 and 1999, when he was riding high in the polls, Chavez never stopped talking about radical, grass-roots democracy, about empowering the people, and opening state decision-making to the masses. That rhetorical line lasted exactly as long as his majority in the opinion polls did.

By late 2001, opinion polls showed vast majorities of Venezuelans favoring a change in tone from the government. 85% of respondents (including, necessarily, a good number of chavistas) told IVAD’s pollsters that they wanted Chavez to “change his attitude.” In effect, what Chavez was proposing was shutting out the majority of the public from the political process…all in the name of “participatory democracy”!

Chavez equated all dissent with treason; all dissidents were branded enemies. It was not hard to recognize the autocratic thrust of this style of politics.

For the government, letting anyone from outside “the process” participate in policy-making would have meant accepting the opposition’s legitimate right to speak for a substantial portion of the country. The government understood that sitting down to talk to those fishermen would have meant honoring the right of dissenters to exercise full citizenship rights, and implicitly abandoning the official fantasy that only hyperprivileged coup-plotters opposed the government. This Chavez has never been prepared to do.

Much of what the opposition wanted was a show of respect from the regime, some symbolic acknowledgment of our right to participate in our political process freely.

By early 2002, after the government had made it clear it would not extend such symbolic recognition, the opposition changed strategies. We imagined we could force the government’s hand by taking to the streets in protest. We figured that if hundreds of thousands of us marched on the streets of Caracas, it would be impossible for the government to continue to dismiss us as an irrelevant plutocratic fringe.

One huge street march after another was organized, some nearing a million participants. Even then, even against the evidence of their and everyone else’s senses, the government continued to dismiss the opposition movement as little more than a coup-plotters’ private club. The vicepresident’s pig-headed refusal to recognize the blindingly evident became the stuff of punchlines (and angry tirades) in opposition circles.

These people do not exist.

It’s not surprising that many in the opposition went possitively batty after being dismissed and villified in this way again and again. To this day, the government maintains that the dozens of polls and scores of marches are a media fabrication. Go through the official media, Venpres or VTV, and you’ll be left in no doubt: a fringe of oligarchical wreckers notwithstanding, the country is overwhelmingly united behind Chavez.

How this profession of faith squares off with their panicked attempts to stop a recall vote has always been particularly hard to understand. But the president’s attitude towards the political rights of those who disagree with him has never been particularly nuanced. Talking about the boxes containing the forms with several million signatures for a recall referendum, Chavez recently said they were “full of trash.”

That, in the end, is what our citizenship rights are to him: trash.

Why, oh why does Chavez behave this way? It’s one of those imponderables, but my guess is that it comes down to his own narcissistic fantasies-cum-ideology. Chavez truly believes he has a democratic mandate for revolutionary change, and if you really think you’re leading a revolution, the notion of recognizing the political rights of counter-revolutionaries and class enemies is plainly nonsensical.

Within the government’s sectarian view of political reality, excluding dissidents makes good sense. If your aim is to politically destroy a given group, what could possibly be the point in reaching a settlement with them? When it comes down to it, you might cooperate with your adversaries, but your enemies you fight.

Cooperate or fight?

At its root, the conflict reveals a wide gulf between the basic political philosophies of the two sides, between the ways that, deep down, each understands political life. The government sees politics as a zero-sum game between social classes. There is a fixed amount of power in society, and social classes continually fight over it. One class’s loss is another’s gain. In order for the poor to win, the rich have to lose. There is no room for negotiation and accommodation between opponents in this simplified Marxist worldview, only struggle.

The opposition, on the other hand, has a pluralist view of political reality. To a pluralist, the total stock of power in society is not fixed; it can grow or shrink over time. Games can be either positive-sum or negative-sum – one side’s gain is not necessarily the other side’s loss – so opponents have a natural interest in cooperating. In this view, the other side’s loss is nothing for your side to cheer about – it could simply mean that you will also lose out soon. To a pluralist, nothing could seem more natural than consulting new policies widely and taking a keen interest in the input of the stakeholders, whether they’re politically close to you or not.

Chavez’s ideology is fundamentally incompatible with pluralist bargaining and cross-class co-operation. The zero-sum view leads him naturally towards maximalism – a tendency to equate consensus with surrender. Ideological rigidity becomes a badge of honor when you see the world in such terms, compromise becomes a matter of shame.

Protests coming from the other side – “the squeals of pigs on their way to the slaughterhouse,” Chavez dixit – come to be seen as indicators that great strides are being made on the road to social justice: if the old elite is really, really unhappy that must mean that they are losing power in society, and if they’re losing power in society that must mean the poor are gaining a corresponding amount of power. Perversely, making the other side unhappy becomes a policy goal, insofar as you see the unhappiness of your enemies as a sure-fire indicator that you’re empowering your supporters.

The possibility that in marginalizing your enemies you might set off a negative-sum game where everyone loses is just never considered.

It’s in this context of a clearly autocratic government determined to exclude all dissenting views that we have to examine what has happened over the last 27 months. Opponents’ reactions to Chavez’s autocracy have sometimes been extreme, destructive and unjustified. Both in April 2002 and in the December-January general strike, it’s obvious to me that the opposition made big, bad mistakes. It’s also clear that those mistakes were over-reactions to very real grievances against a government that had made a point of excluding us from public life.

What Venezuela has learned over the last 27 months is that, in the absence of old-style dictatorial repression, such sectarian governance is deeply destabilizing. The instability it generates makes it impossible for the government to reach its social goals. The gigantic can of worms Chavez has opened in terms of dissent, protest and instability, makes it impossible for his government to help the poor.

Because the dirty little secret is that political life is not, in fact, a zero-sum game. As the last few years should make more than evident, it’s perfectly possible to govern in a way that screws both the rich and the poor. So long as we’re led by those who imagine that every anti-rich policy is, by definition, pro-poor, we’ll be stuck in the miserable negative-sum game Venezuela has become.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate