The petrostate that was and the petrostate that is

Too many foreign observers write about the Chávez era in a historical vacuum. But you can’t understand chavismo without a feel for the political economy of the petrostate.

The Petrostate that was and the Petrostate that is:

I: The Accion Democratica Model

Back in 1996, I did some field work in Cabimas, a dusty little oil city in on the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo, for my thesis on the Venezuelan labor movement. One day, I saw a bunch of guys playing basketball at a municipal court and thought I’d hang out with them for a while – not that I’m any good at basketball, but I thought they might offer a different perspective.

Later, when I told my labor movement buddies what I’d been up to, they were horrified. “What!? You were hanging out with those adeco basketball players? Oh Jesus, did you give them any information?!”

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I’d often read about how deeply political parties had penetrated the fiber of everyday life in Venezuela, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I’d often read about how deeply political parties had penetrated the fiber of everyday life in Venezuela, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.

Undaunted, I went back and asked them about it.

“So, you guys are from AD?”

They kind of smiled awkwardly and one of them said, “well, we needed a court and…”

He went on to tell me the story about how they’d always wanted a proper court to play on, and they’d never had enough money for shoes, balls, uniforms, coaching…all the stuff you need to join a youth league. The mayor of Cabimas was an Accion Democratica politician and one of the guys mentioned his uncle was an AD member, so they asked him for help.

The uncle pointed them to their neighborhood AD party organizer. They went and asked him if the city would built them a basketball court. The organizer said he would be happy to press their case with the mayor, but told them the mayor would be, cough-cough, much more likely to agree to it if they’d sign up to become party members.

The bargain was simple – a chunk of the municipal recreation budget in return for becoming AD members and helping out with election campaigns and get-out-the-vote drives. That didn’t strike the guys as such a bad deal. So they signed up, and after a year or so they’d gotten their court and some gear…with the slight inconvenience that the whole town started to think of them as “those adeco basketball players.”

And there you have it: at its core, that is the Venezuelan petrostate.

The petrostate is a mechanism that turns oil money into political power – or, more precisely, control of the state’s oil money into control of the state – in a self-perpetuating cycle.

The way you do that is by building a huge patronage network. Tammany Hall politics on a national basis.

Those kids shooting hoops in Cabimas had never heard of Terry Lynn Karl, but they instinctively grasped how the system worked. And so did their neighborhood party organizer: he was able to use his influence over a tiny share of the state’s oil revenue – just enough to get a basketball court built – to fund a miniature local patronage network. His clients – the guys – would return the favor on election day, not due to any sort of ideological affinity, but simply to keep their access to his influence over funds. And he would use his influence over them – his ability to mobilize them for political purposes – to bolster his position as client to the next patron up the line: the mayor.

That basic, pyramidal structure was replicated all throughout the country, in every imaginable sphere of life, from multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects to things as petty as a neighborhood basketball court.

The mayor of Cabimas – who was patron vis-à-vis the neighborhood organizer – was in turn client to the next patron up the line: the governor of Zulia state. And the governor played client to his higher up, perhaps a politician or a faction in AD’s all powerful National Executive Committee. And that patron in turn played client to the party secretary general or to the President of the Republic…one neat string of patron-client relationships running all the way from the dusty backstreets of Cabimas up to the presidential palace in Caracas.

Copei, the second party, ran a parallel (if somewhat smaller) patronage pyramid, and MAS, the nominal left-wing party, ran a much smaller and weaker one.

This, basically, was the system Chavez was elected to dismantle. By the time the 1998 elections came around people resented it acutely. But before launching into a (by now redundant) critique of the system, it bears stopping to notice a few of its features.

For one thing, it’s important to realize that the system was not totally paralyzed – the basketball court did get built. No doubt the funds that built it were mercilessly stripped at every step from presidential palace to dusty backstreet as successive layers of patrons took their cut, but the court did eventually get built.

So while it was inefficient, bloated, antidemocratic, and everything else, the system was not totally useless – and in its own amoral way, the corruption served as a rough-and-ready way to spread the oil money around, to make sure it reached many hands, not just a few. The recipients of the final product – the basketball players – were the end-point of a sprawling corruption scheme: it’s just that they got paid off for their services in courts and basketball gear rather than cash.

The Petrostate is a State of Mind

It’s important to note that the Petrostate is not simply a system of social relations – a huge pyramid linking everone who’s on the take – it’s also a cultural system, an interlocking set of beliefs, a state of mind.

In a typical developing country, the overriding political problem is the problem of production: how to generate enough wealth to pull the nation out of poverty. But in a petrostate, production is not seen as particularly problematic: wealth is just there, all you have to do is pump it out of the ground. In a petrostate, the basic political problem is the problem of distribution: how best to spread around wealth whose existence you take for granted. Success in life depends not on work, not on your capacity to produce wealth, but on connections, on your ability to get your hands on a piece of the resource pie.

This outlook comes to dominate people’s relationship with the state. The state comes to be seen as an inexhaustible source of money. People come to believe that whatever problem they have, they state can and should solve it.

Those guys in Cabimas had no doubt that if they wanted a basketball court, it was the state’s job to build them one – after all, wasn’t the country awash in oil money? Insofar as the petrostate has a culture, that’s its central conceit – the idea that the government has so much oil money that it can, and should, bankroll the needs and desires of the entire society.

Within the petrostate mental model that’s what the state is for, and governments are to be judged by how well they deliver on that promise.

That’s not just me saying it – polls consistently find that over 90% of Venezuelans think this is a rich country, with over 80% calling it – incongruously – “the richest country on earth.”

Those beliefs didn’t just appear in the popular imagination by accident. The petrostate’s founding myth was at the center of the AD political program from the 1920s onward. AD’s founding father, Rómulo Betancourt, wrote a number of books on the subject.

Those beliefs didn’t just appear in the popular imagination by accident. The petrostate’s founding myth was at the center of the AD political program from the 1920s onward. AD’s founding father, Rómulo Betancourt, wrote a number of books on the subject.

In his influential book, The Magical State, Fernando Coronil argues that this petrostate mentality extends backwards in time all the way to the presidency of López Contreras in the late 1930s, and is centered on the expectation that the state can magically bring about modernity.

For a while, that redistributive vision worked. So long as the population was relatively small, the state relatively efficient, and the oil revenue stream relatively steady, a simple redistributive strategy went a long way.

Throughout the 40s, 50s, 60s and into the mid 70s, the petrostate model yielded a huge improvement in Venezuelans’ standards of living. Infrastructure got built, people got jobs, and each generation could reasonably expect to live better than the one before. The country got universal schooling, free universities, hospitals, public housing, sewers, phones, roads, highways, ports, airports, and all kinds of markers of modernity decades before other Latin American countries had them.

Less tangibly, but just perhaps even more importantly, the petrostate bankrolled institutions ranging from paid maternity leave and severance pay, to old age pensions and statutory vacation pay, all the way back in the 1960s.

By creating sprawling patron-client networks, the political parties became strong enough to make a limited form of democracy viable. The web of social relationships was quite useful in the early decades of democratization. Patronage webs ensured that enough people were socially and economically attached to democratic institutions to have a personal stake in the political system. This loyalty was the key to keeping the country stable and democratic at a time when most of Latin America was not.

And here’s the wonder: for a long time, it actually worked. There were elections every five years, AD and COPEI routinely and peacefully alternated in power, Venezuela was an island of democracy and stability in a continent torn apart by Marxist insurgents and coup-plotting generals.

Breakdown

But it didn’t last. There are many reasons why the relatively benign clientelism of the 50s and 60s atrophied into the kleptocratic lunacy of the 80s and 90s. Corruption is the typical reason cited, but the truth is both more complex and less morally satisfying than that. The underlying reason for the system’s breakdown, in my view, has everything to do with the increasing volatility of the world oil market, together with appalling mismanagement and good old demographics.

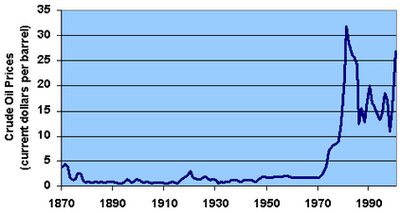

Until 1973, oil had traded in a relatively narrow price range, making Venezuela’s revenues more or less predictable from one year to the next. But starting with the oil embargo in 73 – remembered as the “oil crisis” in importing countries but as the “oil bonanza” here – oil prices started to gyrate wildly, making it impossible to forecast state revenues with any degree of certainty. With each new boom, huge torrents of petrodollars would pour into the Venezuelan economy, only to be followed by busts that were just as marked and unexpected.

This boom and bust cycle was destructive on a number of counts. From a merely macroeconomic point of view, it’s clear that economies don’t do well under that sort of instability.

More destructive than the cycle itself, though, was the state’s chronic mismanagement of the cycle. With each boom, the politicos seemed to think that high prices would last forever, and so they would take out huge new debts even as money poured in at record rates. When prices fell, the boom-time excess would only fuel increasingly acute recessions, made all the worse by the new debt burden that had to be financed. This is the famous debt-overhand hypothesis that some observers blame for the onset of Venezuela’s economic decline in the 1980s.

But I would argue that the most destructive effects of the late petrostate were cultural rather than economic. The massive influx of oil dollars in the 70s shifted public morals in this country. Amidst the abundance of oil dollars, graft became accepted in a way it had never been before. The perception was that only a pendejo, a simpleton, would miss out on the opportunities for easy riches that proliferated in those days for the well-connected. A culture of easy-going racketeering, of matter-of-fact robbery, penetrated deep into the Venezuelan psyche. We’ve never managed to shake it.

At the same time, population growth gradually diluted the oil wealth among a bigger and bigger pool of recipients, making the principle of petrodollar-funded prosperity for all ever less feasible. Even if the state redistributed all its oil rents in cash equally to everyone, most Venezuelans would not stop being poor.

By the late 1980s, the petrostate model had broken down irretrievably. Even if the politicians of the day had been a gaggle of angels gifted with Prussian administrative efficiency, there just wasn’t enough oil money to go around.

Alas, the politicians we had then were the polar opposite of Prussians and anything but angels.

Patrons’ reliance on their clientelist networks made the entire system exceedingly difficult to reform, and particularly deaf to calls for change from the outside. Never particularly suited to ideological debate, the petrostate became ossified completely: power itself became its only ideology. The drive to amass more of it, to climb higher and higher in the pyramid, to gain access to ever more lucrative sources of patronage, came to dominate the political system entirely. As the system became more and more dysfunctional, people’s resentment of the corruption at the heart of the system grew ever stronger, though very few within the state recognized this.

So the late 1980s were a critical moment in the country’s history. Venezuela needed massive reform. It needed to reinvent itself, to leave behind a model of governance that was well past its sell-by date and find a way to integrate itself into the world economy, shedding its reliance on oil, not just as a source of money, but as lynchpin of its socio-political and cultural systems. Venezuela needed to ditch clientelism, reinvent social relations at every level, pry apart the patronage networks that had defined its social relations for so long. We needed to ditch the notion that the state could bankroll everyone’s way of life just by distributing the oil money.

We needed to invent a whole new idea of the state, nothing short of a total rethink of society, the state, and the relationship between the two.

And we failed.

That failure is the reason Hugo Chavez is in power today. His political success is the inevitable outcome of our inability to cast off the petrostate model.

II: Our botched attempt at reform

Back in 1989, all you had to do to realize how badly Venezuela needed reform was pick up a phone. On a bad day it could take half an hour or more to get a dial-tone. You’d unhook the phone, go make yourself a sandwich, check for a dial town, eat the sandwich, check for a dial tone again, wash your dishes and put away the mayonnaise, come back and check for a dial tone again…it was pretty ridiculous.

But once you’d managed to place the call, your troubles had only started: more often than not you’d have to go through the delightful ritual of the llamada ligada – the “linked call.” This was a queer little phenomenon where two entirely unrelated conversations would become entwined in the circuitry somehow, and you’d end up sharing your conversation with two complete strangers. Sometimes, these absurd little four-way interchanges would develop, as each set of callers tried to convince the other set to hang up and try their call again: of course, you didn’t want to be the one to hang up, because then you’d have to wait who-knows-how-long for a new dial tone.

Ah, the days of the nationalized phone company. Working with 40 year old equipment, CANTV (as the company’s called) was far, far behind the technological and service curves. Waiting times for a new phone line could extend into months or years. Predictably, the delays spawned their own little hotbed of corruption: if you needed a new phone line, you had to pay off somebody inside CANTV to bump you to the front of the line.

Phone lines were such a scarce luxury that they carried a premium on the real-estate market: in the classified ads, people selling their apartments would advertise not just location and size, but, proudly, “con teléfono” – an item that would add a good 5% to the price of an apartment. Having a second phone line became the ultimate status-symbol, the height of conspicuous consumption.

State-owned CANTV was prey to all the vices of clientelism run amok. Shielded from competition, the company could get away with bloody murder. As a consumer, you were powerless: a supplicant in the grip of a system that existed more to extract bribes than to provide phone service.

The CANTV-style attitude of total contempt for the user/citizen pervaded the state. Trying to get anything out of the bureaucracy was a nightmare. Registering your car or trying to get a passport or a cédula (a national ID card) became an exercise in frustration-control. Notoriously, even paying your taxes became a problem. Tax officials knew that you needed that little shard of official paper they controlled (the certificate that you’d paid your taxes) for a number of reasons – you couldn’t sell real estate without it, for instance – so you ended up in the incredible position of having to bribe an official for the privilege of paying your taxes! That’s how entrenched the culture of corruption was.

But the rot wasn’t confined to the micro-level: macroeconomically, the country was also in serious trouble. The Central Bank was more or less out of foreign reserves. Protected by years of tariff barriers and subsidies, both private and state-owned enterprises were inefficient, rent-seeking leeches cranking out substandard goods at inflated prices. Business had been thoroughly assimilated into the pyramid: trading political support for subsidies and tariffs in exactly the same way those kids in Cabimas traded political support for basketball gear.

Thirty years of petrostate clientelism had turned the government into albatross around the nation’s neck. The public sector payroll was impossibly bloated. The petrostate had slowly morphed into a full-employment scheme for governing party clients. In 1988, Venezuela had more public employees than Japan, but as the dark joke at the time went, “of course, in Japan they don’t get quality public services like we do here.” Lots of public sector jobs were “no show jobs,” where clients showed up just twice a month to collect their paychecks, but didn’t actually work. Many other officials treated their salaries as a sort of retainer, but everyone understood that the real money was elsewhere – in the kickbacks, commissions and bribes that state jobs gave them access to.

A sprawling state-owned sector of the economy was made up of a single profit-making firm (the oil giant, PDVSA) bankrolling dozens of parasitic, loss-making firms. Money that might have gone to build schools and hospitals went instead to prop up a thousand and one money-holes: state sugar-refineries, banks, mining companies, airlines, even, famously, a fast-food joint in Caracas called “La Sifrina” (que tiempos aquellos!)

People were sick of it, and understandably so. But – and this is a crucial “but” – they didn’t see the need for root and branch reform. What they wanted was to see the petrostate fixed, not replaced. Venezuelans longed for the bonanza days of the 70s, when windfall oil revenues financed a huge and rapid expansion in consumer spending. If they were angry at politicians, it was because they thought politicians had failed to deliver on their basic mission to meet everyone’s needs by distributing the oil money fairly and generously. Do that, they figured, and the country could return to the good old days of the 70s.

Here we get back to the mental model that underpins the Venezuelan petrostate, and its founding myth that Venezuela is a fantastically rich country so all the state has to do is distribute the oil rents for everyone to live comfortably.

If you genuinely believe that, as 90% of Venezuelans still do, but you personally live in poverty, then the obvious inference is that the reason you’re poor is that somebody stole your fair share. Those adeco bastards!

Let me be clear about this: corruption really was a huge problem back then (still is.) But Venezuelans had wildly unrealistic notions how much their lives could improve if corruption was stamped out. Few grasped that even without corruption, the petrostate model was unworkable. The complicated structural and demographic reasons that made it fundamentally non-viable were not a part of the national debate. They were understood only partially even in academic and technocratic circles. So the perception that corruption was the whole of the problem in fact impeded a deeper examination of the real reasons the state had stopped working.

El Gocho pal ’88

Lo and behold, the 1988 presidential election featured a candidate uniquely positioned to play into people’s anger at the state of the state: Carlos Andrés Pérez, who had actually been president once already, from 1974 to 1979, when the first big spike in petrodollars reached the country. CAP, as everyone called him, ran as an old style populist, promising to turn back the clock and govern just as he had the first time around. Venezuelans wanted a revamped petrostate, and he offered a revamped petrostate. Not surprisingly, he won by a landslide.

Now, what on earth CAP was thinking when he ran his campaign that way is still a subject of debate in Venezuela today. Looking back, it’s clear that the state was in no financial position to bankroll the whole of society anymore, and CAP must have known that. Some people think it was all a carefully calculated ploy from the start, that he knew he needed to talk the talk to get elected, but was aware all along that he couldn’t walk the walk.

Now, what on earth CAP was thinking when he ran his campaign that way is still a subject of debate in Venezuela today. Looking back, it’s clear that the state was in no financial position to bankroll the whole of society anymore, and CAP must have known that. Some people think it was all a carefully calculated ploy from the start, that he knew he needed to talk the talk to get elected, but was aware all along that he couldn’t walk the walk.

Not everyone agrees. As one delicious anecdote would have it, CAP was certain that he could revamp the petrostate because he had already worked out a preliminary deal with the incoming US administration. The soon-to-be secretary of the treasury was fully on board for a financial rescue package that would allow the Venezuelan government to keep doing business more or less as usual…and that incoming administration would be run by President Dukakis. Oops.

Well, CAP won with a record number of votes, but of course Dukakis went down in flames. Literally weeks after being elected, CAP found himself at the head of a barely functioning, bankrupt state. He had little choice but to renege on pretty much everything he’d stood for during the campaign.

Well, CAP won with a record number of votes, but of course Dukakis went down in flames. Literally weeks after being elected, CAP found himself at the head of a barely functioning, bankrupt state. He had little choice but to renege on pretty much everything he’d stood for during the campaign.

Instead, he announced a program of massive, IMF-sponsored structural reforms – lifting tariff barriers, dropping subsidies, privatizing state assets…a straightforward neoliberal, Washington Consensus type program.

Now, it’s easy to rant against the IMF, but context is key here. Given the scale of the mess that state finances were in, and the role petrodollar-funded patronage played in undermining state finances, there’s a good case to be made that radical reform was badly needed with or without the IMF. Which, in general, is my critique of the standard critique of the IMF: put forward in a context-vacuum, it fails to take note of the entirely Venezuelan reasons why reform was necessary to overcome the bottlenecks generated by petrostate clientelism.

Be that as it may, it’s also true that CAP’s reforms were a bald-faced betrayal of everything he’d stood for just weeks before he announced.

Venezuelans thought they’d elected CAP to fix the petrostate, instead, he immediately moved to dismantle it. It barely made a difference that the petrostate was badly in need of dismantling: anyone needing a phone-line in those days should have been able to see that. Consensus on the need for reform was confined to technocratic circles – the public sphere just was not on board.

CAP didn’t seem to think he had to make the case for dismantling the petrostate. He thought he could just do it, steamroll over all opposition and present the country with a fait accompli. His thinking, apparently, was that the economic benefits of reform would be so evident within a couple of years that the critics of reform would be marginalized.

Alas, he miscalculated badly. First off, CAP was elected on an AD ticket, as the candidate of the party that benefited the most from the petrostate model. In fact, arguably the main source of resistance to CAP’s reform push was his own party. CAP might have had a road-to-Damascus moment sometime after the Dukakis campaign imploded, but the rest of AD was still very much wedded to petrostate clientelism. And CAP’s reforms were plainly incompatible with their vision of the state.

Take CANTV. Sure, it was a nightmare for consumers, but who cares about consumers? For the AD patrons who ran it, the phone company was a cherished power-base. Not only could they exploit their control over a scarce commodity – phone lines – to demand any number of bribes, enriching themselves and feeding their personal patronage networks, they could also use the company to listen in on their opponent’s phone conversations, to distribute CANTV jobs to clients, and, of course, to install multiple phone lines in their own homes. If you privatized the company, the phone system might start working, but the whole patron-client network it sustained would come crashing down.

A similar dynamic was in play in dozens of state institutions CAP wanted to sell off, streamline, or reform. Every ministry and university, every state owned enterprise and autonomous institute, every piece of the petrostate had a powerful set of AD caciques dead set against reform.

CAP’s reform package would drive a dagger through the heart of the party’s whole racket – not surprisingly the caciques mobilized furiously against the president they’d just helped to elect.

Soon, CAP found himself engulfed in a rising tide of unmanageable protest and dissent. Every scrap of reform met strong resistance in congress, where the caciques still had a majority. AD patrons exploited people’s strong adherence to the petrostate cultural model to fuel resistance to reforms that would undermine their power bases. The IMF was predictably demonized, as was CAP for caving in to its demands.

Many Venezuelans were genuinely outraged at what they saw as an unacceptable onslaught on their petrostate perks. In the end, too many people were too dependent on the cash that flowed through the patron-client networks for reform to be viable – and those who stood to lose the most were particularly easy to mobilize politically, precisely because they were part of a pyramid that made political loyalty to your patron rule #1.

From 27F to 4F

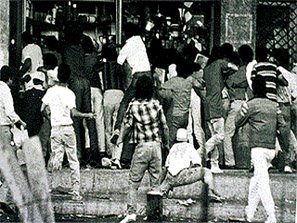

The straw that broke the camel’s back came when the government cut back its fuel subsidies at the end February 1989. Public transport operators responded to a 10% increase in gas prices by doubling fares, and the shit hit the fan.

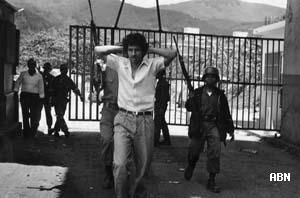

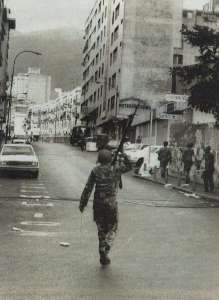

On February 27th, 1989, a group of far-left agitators in Guarenas, a Caracas suburb, staged a protest over the fare hikes that soon escalated into a riot. The riot spread incredibly quickly, first to Caracas itself and then throughout the country. For three days Venezuela went through an unprecedented spasm of rioting, arson, and very widespread looting. The police was helpless in the face of this sudden outburst of anarchy. Eventually, the government called out army troops with orders to shoot looters on sight. At least 600 people were shot dead in the next two days, by some estimates the real toll was over a thousand. The bodies were dumped into mass graves – a practice Venezuela had not witnessed in many decades.

On February 27th, 1989, a group of far-left agitators in Guarenas, a Caracas suburb, staged a protest over the fare hikes that soon escalated into a riot. The riot spread incredibly quickly, first to Caracas itself and then throughout the country. For three days Venezuela went through an unprecedented spasm of rioting, arson, and very widespread looting. The police was helpless in the face of this sudden outburst of anarchy. Eventually, the government called out army troops with orders to shoot looters on sight. At least 600 people were shot dead in the next two days, by some estimates the real toll was over a thousand. The bodies were dumped into mass graves – a practice Venezuela had not witnessed in many decades.

It was the end of Venezuela’s age of innocence.

The effect the 1989 riots had on Venezuela’s public life was in some ways analogous to 9/11 in the US, an event so deeply traumatizing it could be summoned just by its date: 27F. Until then, Venezuelans had seen themselves as different, more civilized, more democratic, better than their Latin American neighbors. 31 years of unbroken, stable, petrostate-funded democracy had made us terribly cocky. In a sense, the riots marked Venezuela’s re-entry into Latin America. The country was no longer exceptional: just another hard-up Latin American country struggling to put its democracy on a stable footing.

CAP’s reform program was seriously hobbled by the riots, but it continued, at half-steam, for another 4 years. Economically, it was a relative success – after a serious recession in 1989 that saw the economy contract by 10.9%, Venezuela experienced real economic growth for the first time since the 70s. Real per capita income was expanding steadily: 3.9% in 1990, 7.1% in ‘91, 3.6% in ‘92 – though, again this was helped by the spike in oil prices following Irak’s invasion of Kuwait. From a narrowly economic point of view, it seemed to be working.

CAP’s reform program was seriously hobbled by the riots, but it continued, at half-steam, for another 4 years. Economically, it was a relative success – after a serious recession in 1989 that saw the economy contract by 10.9%, Venezuela experienced real economic growth for the first time since the 70s. Real per capita income was expanding steadily: 3.9% in 1990, 7.1% in ‘91, 3.6% in ‘92 – though, again this was helped by the spike in oil prices following Irak’s invasion of Kuwait. From a narrowly economic point of view, it seemed to be working.

But none of that mattered to the old-style patrons, the 10,000 little caciques heading up administrative fiefdoms large and small throughout the state. What they cared about was power, and CAP’s program constituted too big a threat to their habitual way of getting it. From their perches in AD’s National Executive Committee, in congress, in the courts, the nationalized companies and the labor movement, they were extraordinarily well placed to wreck the reform drive.

It was during the third year of this CAP vs. AD psychodrama that a certain army lieutenant colonel first entered the public scene…and with a bang. On February 4th, 1992, a group of junior officers launched a bloody coup attempt against the elected government. The crazy adventure – the first time someone had tried to overthrow a Venezuelan government by force of arms since the 60s – left about a hundred dead, and earned its own instantly recognizable date-moniker: 4F.

It was during the third year of this CAP vs. AD psychodrama that a certain army lieutenant colonel first entered the public scene…and with a bang. On February 4th, 1992, a group of junior officers launched a bloody coup attempt against the elected government. The crazy adventure – the first time someone had tried to overthrow a Venezuelan government by force of arms since the 60s – left about a hundred dead, and earned its own instantly recognizable date-moniker: 4F.

The coup attempt failed, but it turned its leader into a kind of folk hero – the valiant paratrooper willing to put his life on the line to stop CAP’s outrageous drive to dismantle the cherished petrostate, and a rare Venezuelan public figure willing to forthrightly accept responsibility for failure.

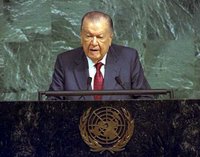

The coup-plotting lieutenant colonel went to jail, where he whiled away two years reading (but not understanding) Rousseau, Bolivar and Walt Whitman. In those two years, the government faced a second, even bloodier coup attempt by officers loosely associated with the first. Eventually, CAP was impeached by his fellow AD party members on flimsy charges, and after a brief interim government, the presidency passed to yet another petrostate dinosaur – Rafael Caldera, who had also been president already, but even further back than CAP, in 1969-1974.

Like CAP, Caldera ran as an old style populist. Unlike CAP, Caldera governed like one.

By the time he reached power for the second time, Rafael Caldera was over 80 years old. He’d spent 58 of those years in front-line politics. Frail, some would say decrepit, his voice tremulous and often barely audible, he wasn’t exactly the kind of leader you’d turn to for bold new ideas. Caldera tried to patch up the old petrostate system – the only one he understood – as best he could.

Predictably, he failed. Corruption continued unabated, cronyism as well, and much of the banking sector collapsed in 1994, wiping out the lifetime savings of thousands. The economy languished, and the nation’s collective impoverishment continued afoot. Eventually, Caldera was persuaded of the need for some reform, including an important overhaul of the criminal system and of social security. But he didn’t understand, much less share, the notion that the basic model of the state he had spent a lifetime championing needed a total overhaul.

Predictably, he failed. Corruption continued unabated, cronyism as well, and much of the banking sector collapsed in 1994, wiping out the lifetime savings of thousands. The economy languished, and the nation’s collective impoverishment continued afoot. Eventually, Caldera was persuaded of the need for some reform, including an important overhaul of the criminal system and of social security. But he didn’t understand, much less share, the notion that the basic model of the state he had spent a lifetime championing needed a total overhaul.

If the petrostate was well past its sell-by date in 1989, by the end of Caldera’s term in 1998 it was putrefact. Nobody doubted that the country needed a serious shake-up, a massive jolt to move beyond the stagnation and decay of the last 20 years.

Indeed, all three of the politicians who ever looked to have a serious shot at power that year were anti-establishment figures, people who’d built political careers outside the traditional party system.

The country faced a choice between a one-time Miss Universe turned centrist mayor of a wealthy district of Caracas (Irene Saez) a Yale graduate and reformist governor from Carabobo State (Henrique Salas) and the aforementioned leftist Lieutenant Colonel (who’d been pardoned by Caldera and released from prison in the meantime.)

The country faced a choice between a one-time Miss Universe turned centrist mayor of a wealthy district of Caracas (Irene Saez) a Yale graduate and reformist governor from Carabobo State (Henrique Salas) and the aforementioned leftist Lieutenant Colonel (who’d been pardoned by Caldera and released from prison in the meantime.)

Disenchantment with the old party structures ran so deep that Copei didn’t even bother to try to run a party insider as candidate. Instead, they tried to co-opt the beauty queen, who collapsed in the polls the second she accepted their nomination. As always, AD was the last to get the message: they nominated Luis Alfaro Ucero, a semi-literate 80 year-old cacique, a sort of capo di tutti i capi sitting at the pinnacle of the party’s patronage structure. The guy never got beyond 7% in the polls. The vaunted adeco electoral machine had sputtered to a halt.  Soon enough, it was all down to the governor and the coupster, and it was clear that the election would go to the one who best voiced the people’s virulent rage at the ongoing failure of the petrostate.

Soon enough, it was all down to the governor and the coupster, and it was clear that the election would go to the one who best voiced the people’s virulent rage at the ongoing failure of the petrostate.

And if that’s the game you’re playing, nobody but nobody beats Hugo Chavez.

III: From institutional clientelism to the Chavista cult of personality

The scene went down in the middle of one of his infamous, never-ending televised speeches in 2004. President Chavez had barely hit his stride when something caught his eye. His tone changed. Concerned, he looked up at the scaffolding above the stage he was using, where the lights for his speech hung.

“Hey, come down from there,” he said in a soft, fatherly tone, “no, don’t climb to the front, it’s hot there because of the lights…that’s right, climb down towards the back. Don’t worry, you’ll get to talk to me. I want to hear your problem. I saw you crying earlier, just, just come down from the scaffolding and come up here.”

Soon, a 15 year old kid has climbed down from the scaffolding and is walking towards the stage. He’s crying. Chavez calls him up to the podium. With the camera’s running, millions of people watching, Chavez takes him, hugs him hard and holds him for, oh, 45 seconds or a minute, while he the kid tells him, in between sobs, how his father recently died and his mother is sick and he can’t afford the medicines to make her better…Chavez listens at length, pets his hair, assures him that he’s going to help him.

The crowd is ecstatic, chanting “that, that, that’s the way to govern!”

Welcome to the new era of chavista postinstitutional clientelism. This sort of thing is typical of Chavez’s governing style. The president works hard to make the entire audience feel how much he wants to help them all, personally, one by one. And he has succeeded brilliantly at selling the image of a president deeply, passionately, personally concerned with the problems of his supporters.

Obviously, this brand of clientelism is quite a different animal from the old adeco version. Just as obviously, it’s still clientelism.

Chavez’s peculiar contribution to the concept has been to cut out the middlemen. In the old system, each client’s relationship was with the patron immediately above him. But the chavista patronage system only has two levels: the president and everyone else. These days, the relationships that underpin the system happen are televised, they are mediated rather than personal – the charismatic leader’s bond with each of his followers individually.

Chavistas are, in a sense, imagined clients.

Though Chavez has spent billions of dollars on emergency social programs that effectively re-distribute petrodollars to his political supporters (the famous misiones) I’d argue that his success has almost as much to do with raw sentiment, with primary identifications. Many chavistas feel deeply, personally, almost mystically wedded to the president – the intensity of their emotions towards him are hard to overstate.

That’s a departure from what we’d seen before. In the old system, the relationship between patrons and clients was basically a quid-pro-quo, a matter of mutual interest. Insofar as feelings played into it at all, they didn’t go beyond a certain deference born of respect and fear of the boss. With Chavez, the bond comes from the heart. He is so charismatic, his rhetoric is so powerful, that he makes people want to see him as a saviour: they want to cry on his shoulders, they want to redeem themselves through him.

In other words, Chavez’s bright idea for moving beyond the outdated system of vertical interpersonal relations is to replace it with a cult of personality.

It’s bad news.

In the old system, the state had two fully independent institutions: AD and Copei. It’s true, it’s regrettable that there were only two real institutions around, that the courts and the elections authorities and the nationalized companies and every other part of the state was subjugated to one party or the other. But at least there were two of them!

To a certain extent, AD and Copei served to balance each other off. No truly transcendent decision could be made without at least a tacit agreement between the two.

Moreover, each of the two big parties was a complex institution in its own right. Their National Executive Committees were composed of factions that had to deliberate with one another to set the party’s position on any given issue. Each faction would press the interests of a given constituency – the pro-business faction would haggle with the labor bureau to agree on the party’s minimum wage policy and the peasant representatives would hash out the party’s position on agricultural imports in talks with the technocrat wing. Each party had its own internal deliberative process. It was hardly a model of tocquevilian pluralism, granted, but at least some deliberation and interest-aggregation took place.

In the chavista state, there is only one institution: Hugo Chavez. Note that I’m not talking about an abstraction – about “the presidency of the republic” – I’m talking about a man. When an important policy decision has to be made, the only deliberations that matter take place between his ears.

All loyalties are directed at him personally. Supporters direct gratitude for the misiones not at the state in some abstract sense, or to a patron they know personally, but at Chávez personally. With the president locked in a circle circle of relentlessly sycophantic collaborators, all dissent is equated with treason. So the one man who makes every relevant decision personally is never confronted with a view of the world that differs one iota from his own.

The postinstitutional petrostates flattens the distinctions between state, government, party, presidency and president. The result is an accelerated decay in the state’s institutional structure, to the point where no part of the state can act independently of Hugo Chavez personally. Venezuela today is an exercise in turbocharged personalism.

Clearly, some aspects of the petrostate model have changed – everyone recognizes this. What I’d like to highlight, though, are the elements of continuity – elements that are often underestimated in commentary about Chavez. If the basic petrostate trick is to turn control of the state’s oil dollars into control of the state, Chavez has merely brought the system up to date, yielding a petrostate for the 21st century.

Of course, Chavez thinks of himself as the pre-eminent critic of the post-1958 state. But his critique is based on ideas that have been at the heart of the petrostate’s cultural model all along. Chavez certainly thinks he’s rebuilding Venezuela’s political and social structures from the ground up. But like so many self-described revolutionaries before him, he’s blind to how much his vision has in common with the old regime.

The central conceit of the petrostate cultural model is the idea that the state can and should use its oil wealth to bankroll society. Rather than a critique of the petrostate as such, what Chavez provides is a critique of the way it went astray in the 1970s and 1980s, and particularly of “neoliberalism,” understood here as CAP’s attempts to dismantle it.

Chavez doesn’t realize it it, but that outlook places him squarely in the intellectual tradition pioneered by Romulo Betancourt more than 50 years ago. Ultimately, Chavez is just peddling a very old petrostate line – the old longing to fix the petrostate, to reform the unreformable.

That longing has been the key to his political success. In beating the old petrostate drum, Chavez taps into a rich vein of Venezuelan culture. In the end, breaking the petrostate as social system is child’s play compared to the monumental task of breaking the petrostate as an idea, as a collective understanding of what the state is for. And Chavez never challenged the dominant understanding on that score, he merely leveraged it to his own advantage.

The sharp spike in world oil prices since 2004 has given the petrostate a reprieve, but not a pardon. In a virtual re-run of the 1970s, a huge consumption boom is being financed with the extra money, along with a sharp spike in public sector debt. As the good times roll, Venezuelans have come to believe that Chavez made good on his promise. But it’s a reprieve that will last only as long as oil prices hold. And if there’s one thing we should’ve learned a long time ago it’s that gambling your entire strategy on the hope that oil prices will never fall is a deeply foolish thing to do.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate