Exporting Judicial Terrorism

Two elder writers in Eastern Venezuela, a photographer in Paris… the ruling elite is suing citizens who pose no danger for the regime. The abuse of power goes beyond staying in control, it’s also used for personal matters

Photo: Sofía Jaimes Barreto

On May 18th, Andreína Mujica, a Venezuelan photographer and journalist who worked for many years for people like Carlos Cruz Diez, found a letter in her mailbox at her apartment in Paris, where she’s lived for more than ten years.

This letter was signed by a police officer, Clémence Paris, who summoned Mujica to the police station of the 16th arrondissement for interrogation on June 7th at 2:00 p.m.

According to the letter, Mujica was under suspicion of “committing or attempting to commit the infraction of DEATH THREAT BY WRITING, IMAGE OR OTHER OBJECT, committed on March 11th, 2019, in the XVI arrondissement, Paris (ON FACEBOOK).”

Deportation wasn’t her first thought; Mujica is an Italian citizen and is perfectly legal in France, where she works as a photographer and a cook. Seconds later, she realized that on March 12th, 2019 (and not March 11th, her accuser’s mistake) was the date a friend of hers—a friend of Caracas Chronicles, as well—was detained by SEBIN when he was leaving a radio station on his bike to go home: Luis Carlos Díaz.

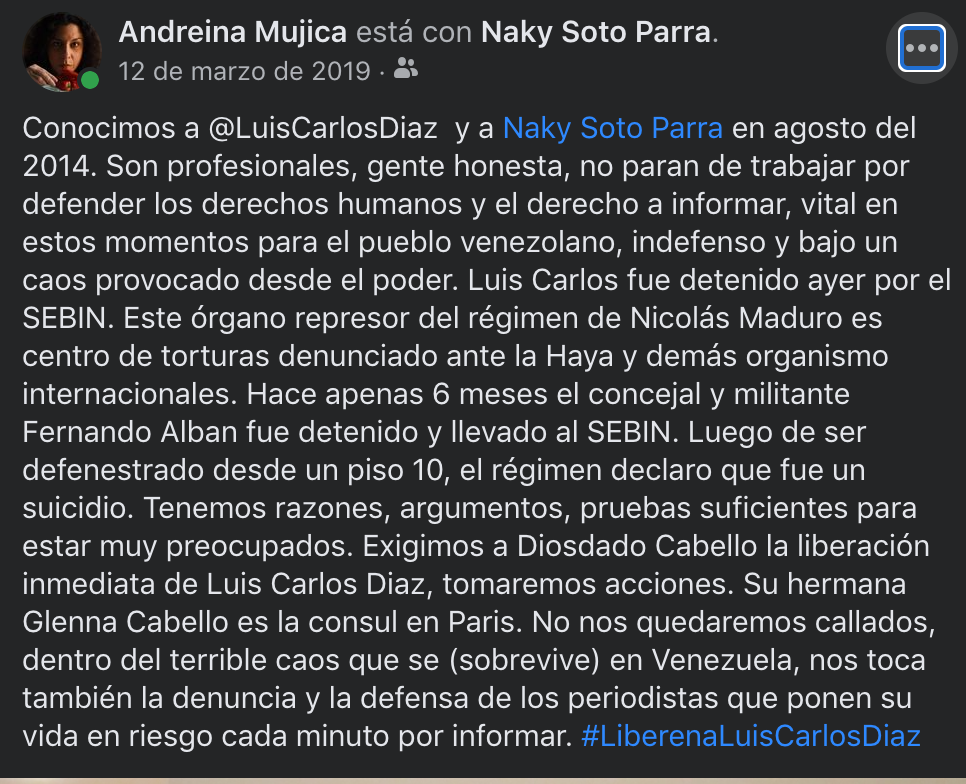

This is what Mujica wrote that night on her Facebook, in similar terms to thousands of Venezuelans:

She demanded that Luis Carlos be released and added that the Venezuelan consul in Paris was Glenna Cabello, sister of the man who, Mujica said, controlled SEBIN: Diosdado Cabello. Mujica remembered that her post on Facebook sparked some heated comments. One of them was from a guy who wrote: “death to Diosdado Cabello!” Another one, on March 12th, 2019, was written by Glenna Cabello herself. Her tone wasn’t a diplomat’s, it was the tone of Diosdado’s sister: “You couldn’t be more stupid.”

Once she got the letter from officer Paris, Mujica called friends for advice and remembered she once interviewed François Zimeray, a former French ambassador in Denmark, a human rights lawyer at the International Criminal Court and the Paris appeals court. His firm is linked with Doughty Street Chambers, the firm where Amal Clooney works.

Mujica called Zimeray, who was perfectly informed about who Diosdado Cabello is, and he agreed to defend her pro bono. They prepared her case and Mujica attended her almost two-hour-long interrogation alongside lawyer Louise Dumas.

Then, she learned that Glenna Cabello had introduced a complaint against Mujica on March 14th, 2019, but was ignored until officer Paris was transferred to this precinct, got up to speed with the pending cases, found a complaint from a foreign diplomat who was claiming death threats against her and summoned Mujica.

During the interrogation, officer Paris read the complaint made by Glenna Cabello. The consul said that Mujica organized a movement against her that implied risk of death for Cabello and her family. Mujica answered all the questions and handed officer Paris a lot of material on our country’s human rights situation, including UN reports and the multiple accusations and sanctions on the accuser’s brother. Then she was released, without preventive measures. Mujica remains totally free and can even leave France if she wants, as long as she can go back if required because the process hasn’t ended: a city attorney needs to see the dossier and decide whether it goes to trial or not.

Mujica’s defense, Zimeray & Finelle Avocats, released a statement where they reject Venezuelan diplomats harassing journalists abroad while the independent media in the country suffers “brutal repression”. The firm says that Mujica was only exercising her freedom of speech and that they’re considering suing Glenna Cabello for defamation.

In a democratic society that Facebook post by Mata Gil, would have been the subject of a legitimate and necessary debate about the limits of freedom of speech, or about how comfortable some writers are with racism, for instance. But here, with Venezuela at the bottom of the world rankings in democracy and all kinds of freedoms, that discussion is hidden under the loud, heavy hand of a ruling caste where anyone feels it’s his or her right to launch an armed squad and a partial court against anyone who offends them.

Mujica awaits the next development in the case. Meanwhile, she’s been talking to Venezuelan media, Amnesty International France and Reporters Sans Frontiers. Three Venezuelan writers in France, Spain, and the U.S.—Golcar Rojas, Carol Prunhuber and Elizabeth Burgos—opened a campaign encouraging people to sign in support of Mujica on Change.org.

There’s a couple of details around this case of family nature, although not of the Cabello family, but Mujica’s. Her father was a legendary journalist, the late Hector Mujica, and a known communist. Her brother Michel Mujica was Maduro’s ambassador to France until December 2020. He and Andreina have had no contact since 2017 after she publicly exhorted him to stop supporting Maduro.

There’s also more to the context here, besides the obvious fact of a dictatorship behaving like one. When the officer unearthed that accusation against Andreina Mujica in France, we saw similar cases in Venezuela.

In April, CONAS and FAES agents detained Milagros Mata Gil and her husband. Mata Gil, a novelist and academic, is 69 years old. She lives in El Tigre, the city in Anzoátegui where the regime’s prosecutor general Tarek William Saab is from. Mata Gil had published a Facebook post where she denounced that Saab attended a luxury wedding in Lechería linked to many COVID-19 cases. A day after being taken to court by a heavily armed squad, Mata Gil and her septuagenarian husband were released on probation.

The same happened to another writer, Rafael Rattia, in Maturín this month. He penned an article about the recently deceased Education minister Aristóbulo Istúriz for El Nacional, the newspaper whose headquarters was recently taken over by a court, as a result of a long suit initiated by no other than Diosdado Cabello.

Rattia’s piece is full of insults. It’s not the kind of piece I would have agreed to publish in Caracas Chronicles, and not because I respect Istúriz or the Maduro regime, but because it isn’t the kind of writing I’m interested in promoting as an editor or the kind of journalism I believe in. In a democratic society, that piece, or that Facebook post by Mata Gil, would have been the subject of a legitimate and necessary debate about the limits of freedom of speech, or about how comfortable some writers are with racism, for instance. But here, with Venezuela at the bottom of the world rankings in democracy and all kinds of freedoms, that discussion is hidden under the loud, heavy hand of a ruling caste where anyone feels it’s his or her right to launch an armed squad and a partial court against anyone who offends them. No matter if they’re old writers with little influence, living the hard lives of Venezuelan seniors in hot, violent, impoverished cities of Oriente. No matter if they’re Venezuelan photographers in France, with no political activity, as dangerous to the wealth and power of the chavista elite as any ordinary Venezuelan migrant can be. They had to experience the rage of the powerful.

See, chavismo’s actions are well beyond being motivated by moral or social justice. They don’t care about having the moral high ground, even in the smallest of instances. For them, it’s all about retaining power, about remaining untouchable, by intimidation or any means necessary. It’s about violence.

There are investigative journalists abroad being harassed by the Maduro regime or their multiple associates. ArmandoInfo’s Roberto Deniz is the subject of a multinational discrediting campaign for his investigations on Alex Saab. And in a Madrid court, David Placer faces a defamation accusation from two Venezuelan businessmen, Jorge and Francisco Neri, who sued Placer for the comments he made about them on YouTube and Instagram after he wrote an article on their past businesses with PDVSA roja rojita.

But the case against Mujica, Mata Gil, and Rattia are of a personal nature. Glenna Cabello probably knows that she can’t prove Mujica was a threat to her life to a French court. Diosdado’s sister must be quite aware she’s not in Venezuela. But she accused Mujica of that Facebook post anyway.

Maybe that’s what she thinks her diplomatic position is for. And that feeling, that behavior of rubbing their power in our faces, is what explains many of the actions and omissions of the people who have been ruling our country for so many years.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate