The Families that Fled Tyranny. Twice.

Madelin Martínez fled Cuba for Venezuela to escape Fidel Castro, only to do it all again when Hugo Chávez rose to power. Here's the first of three stories of families forced to flee tyranny again and again.

One afternoon last December, I was chatting with Madelin Martínez as she blow-dried my hair at a salon in Miami. Four months earlier, Madelin had left her own beauty shop in Caracas in hands of her brother-in-law. Venezuela’s economic chaos and astounding levels of crime had driven her to seek a new life in the United States along with her husband and children.

“You’d wish you never had to migrate, mi niña,” she said. She turned off the blow dryer and looked into the mirror to meet my eyes. “It is exhausting. And scary.”

This was not the first time she’d felt forced into such a life-changing decision. Thirty five years earlier, when she was just 17, Madelin and her family fled Fidel Castro’s Cuba for Caracas. In 2015, she found herself in the same position, looking to escape another government whose policies proved too limiting. “It felt like I had really bad luck,” she said between ironic laughs.

The Martínezes are among thousands of Cubans who fled to Venezuela after Castro came to power in 1959. Venezuela used to be the second largest site of Cuban diaspora, after the United States, with some 40,000 Cubans calling the country home in the 1980s. But the numbers began to drop dramatically once Chavez came to power. Today, just 10,000 Cubans remain in in their adopted homeland.

For Madelin, uprooting herself for the second time in 30 years has been a long, tough journey to peace of mind. Leftist regimes have been hemming in her fate since Dec. 31, 1958, six years before she was even born. On that night, the then president of Cuba, Fulgencio Batista, escaped to the Dominican Republic, ending seven years of brutal dictatorship and prompting a triumph for Castro and his five-year-old 26th of July Movement.

Madelin Martínez at the salon she used to own in Caracas.

In the early hours of the following day, Castro, then 31, came down from the mountains where his movement had been waging guerrilla warfare, and headed to Santiago de Cuba.

“The Revolution starts now,” he said, addressing an uproarious crowd of thousands. He declared the formation of a new government and marched across the island, entering Havana on Jan. 8.

Madelin Martínez’s parents, now divorced, were teenagers then. Her mother, Norma Fanego, was 12 and her father, Rolando Martínez, was 14. They had not yet met, even though they both lived in the same Havana neighborhood of El Cerro. They joined in the celebration with their neighbors, holding up signs and shouting slogans as they tussled with the crowds to get close enough to Castro to touch him as he paraded by.

Seated on the living room sofa of the house Madelin Martínez left behind in Caracas, her father, now 74, recalled how rapidly Communist and totalitarian policies took hold in Cuba. By the beginning of 1960, the Revolution had sentenced and executed about 490 opponents of the new regime. Near the end of the year, the United States declared its embargo and in the middle of 1961, conducted the failed Bay of Pigs Invasion.

Later that year, Castro publicly declared himself a Marxist-Leninist. He closed newspapers and expropriated all privately owned companies, including oil refineries, factories, and casinos.

“Not just that! Everything,” Rolando, Madelin’s father, said. “The man who had a little stand of mangoes, the kiosk at the corner. Every little commerce.”

Rolando has a tendency to repeat himself and go off on tangents, like the one about why he divorced Madelin’s mom and married Isabel, another Cuban woman whom he later also divorced once in Venezuela “because she smoked cigarettes.” He married a third woman, a Venezuelan this time, because “Venezuelan women are beautiful.”

Rolando Martínez, at the house his daughter Madelin left behind in Caracas.

But it was when he spoke about the events that drove his family from Cuba that he showed the most emotion. His voice got louder at those points, his tone was passionate but laced with cynicism, his small blue eyes opened wide.

Suddenly there were no ingredients to make the products with.

When the government expropriated La Estrella, the confectionary company that employed Rolando’s father, the older man kept working as a distributor, but for a new owner: the revolutionary government. Under the supervision of a commander of the regime, Rolando Martínez’s father —Madelín’s abuelo— drove his truck to shops around the neighborhood and stocked them with the popular La Estrella candies, chocolates, and cookies. Soon his wage dropped.

“Suddenly there were no ingredients to make the products with,” Rolando said. There was no chocolate to make the Spanish turron with . . . the specialty of La Estrella. He clearly shared the locals’ fondness for turrones before they —like so many other high quality products— disappeared from the Cuban market. He said that before the raw ingredients started to become unavailable, the La Estrella factory even employed an expert Spanish turronero to guide production of the nougat-style treat.

Rolando met his future wife at a social gathering near his home in 1962. They soon started dating. He was 17 years old and working as a draftsman at a government-owned company that built steel structures. With thin chalk, he drew the construction layouts of the bridges, roads and buildings that designers described to him. It was a job he loved, despite the poor pay. Norma Fanego was 15 years old and starting her senior year of high school. To help out with her family’s finances, every morning before she went to school, she worked in a factory, wrapping candy.

Rolando Martínez was happy enough with his work, but there was trouble at home. His 19-year-old brother Reinaldo —Madelin’s uncle— was involved with an anti-government group and his family feared that he could be arrested. Although Reinaldo had fought alongside Castro against Batista, he had come to believe that the country’s new leader was betraying the Revolution and joined the Jóvenes Desafectos.

“They realized that they had overthrown the Devil to replace him with Lucifer,” Rolando said between laughs. In 1963, a government intelligence official infiltrated a meeting where the group discussed plans to steal arms to incite a revolt. Reinaldo was sentenced to nine years in prison.

One year later Rolando Martínez and Norma Fanego married. He was 20 and Norma, 18. Unable to find housing of their own, they moved in with Rolando’s parents.

I met Norma —Madelin’s mom— in her first floor apartment near Miami International Airport. She’s 70 now, a matron in comfy sweatpants with burgundy-tinted hair. Seated in a big leather chair she asked countless nervous questions about my intentions before she started speaking excitedly and at length. She said the home of her parents-in-law, with their son in prison, “was a house of mourning.”

By then Norma was working in a Havana beauty shop that the government had expropriated. In 1964, when she got pregnant with a baby she would name Madelin, clients brought her what were precious gifts in a time of such scarcity: diapers and milk.

As the regime took control of all the production in the island and started subsidizing products, the supply of everything, even the most basic goods—in fact, especially the most basic goods—became precarious. To deal with the food distribution problem, the government imposed the tarjetas de racionamiento — a rationing system. Like food, cars, home appliances, medicines—almost all products became hard to come by.

To stay out of trouble, Madelin’s parents would work at a Revolutionary Committee office near their house every other Sunday. They patrolled the neighborhood to see if anyone was involved in counter-revolutionary activities. They always returned with a blank report. They hated the job. They also bartered for products they lacked. Norma once worked at the salon for weeks without pay “because I needed a fridge,” she said, “and they gave it to me.”

Every week, Rolando would help his mother—Madelin’s abuela— carry pots of lima beans to the tiny Isla de Pinos, now known as Isla de la Juventud, where his brother was serving out his sentence at the Presidio Modelo, but he was not allowed inside. Only their mother was. On one of their visits, the imprisoned Reinaldo gave their mother a gift for Rolando, a belt that he made with nylon. When Rolando put the belt around his waist, its two ends barely reached the bones on the sides of his hips. He burst into tears. “‘How does this fit my brother,’ I said, ‘if he was so built. How is my brother doing then?” he asked his mother, “ How does he look?’”

By the time her uncle Reinaldo was freed, 9 years later, Madelin Martínez was seven years old and had a three-year-old brother, Reinaldito. Two years later, her parents, Norma and Rolando got divorced. Madelin and Reinaldito stayed with their father and their mother moved back in with her own parents.

At home, Madelin often heard anti-government comments, especially from her uncle. Her father Rolando warned her never to repeat anything at school. “I lived terrified that something would come out of my mouth,” she said.

One day a teacher asked her if her family was planning to leave the country, and she said yes, because she had heard that her uncle was making arrangements. If the government got wind of a family’s plans to leave, they usually lost their jobs and found no new opportunities. And there was shunning. Neighbors would gather in the streets to throw eggs and shout, gusanos, traidores. Luckily, Madelin’s teacher did not pursue the question further.

Other than fear of saying more than she should, Madelin remembers her childhood in Havana as “rather boring and simple,” but happy. “Cubans have great personalities,” she said. “They are joyful people, they are always joking and partying. But if you made a party, there was not much to eat or drink, so just sharing time with people was pretty much what we did. There were no soft drinks, no chocolate, no candy.”

She played at friends’ houses, drew with chalk on the sidewalks, or played soccer in the streets. In the summers, she and Reinaldito had to spend 45 days at a state work camp. They woke up at 5 a.m and stood for hours on trucks until they got to the fields where they spent the rest of the day picking potatoes and tomatoes. They ate mostly rice with beans, or whatever their parents managed to bring them on Sundays, when they were allowed to take the long trip to visit them.

Sometimes, during the school year, there were forays for ice cream at Copelia, when it was available, or to the movies, where technical glitches would often bring the screening to an end mid-show.

“Charisma,” Rolando said with a nod. “It is what all dictator’s rely on for power. From Hitler to Chávez.

Rolando Martínez recalled a night at the movies in the late 1970s when a Castro newsreel interrupted the screening. His address included reference to Cuba being “on the right path,” in a “sea of happiness.” Rolando found Castro’s words so moving, they gave him goosebumps, even though he was not a fan. “It was incredible,” Rolando said. “I turned to my friend and told him to look at my skin. And he said, ‘That is the power of good speech.’”

“Charisma,” Rolando said with a nod. “It is what all dictator’s rely on for power. From Hitler to Chávez.”

By 1980, Rolando’s brother Reinaldo managed to gain passage to Venezuela, which had begun to receive hundreds of ex-Cuban political prisoners. As Professor Holly Ackerman explains in an essay, this arrangement between the two countries was mutually beneficial. Castro was glad to get ¨dissenters¨ out of the country instead of keeping them in the prisons or unemployed in the streets, and the Venezuelan government welcomed the optics of accepting communism’s opponents. The Cuban expat community in Venezuela was happy to absorb them. Once in Caracas, Reinaldo Martínez hoped his ex-prisoner status would help him obtain visas for the rest of his family, including Norma, as the mother of his nephews.

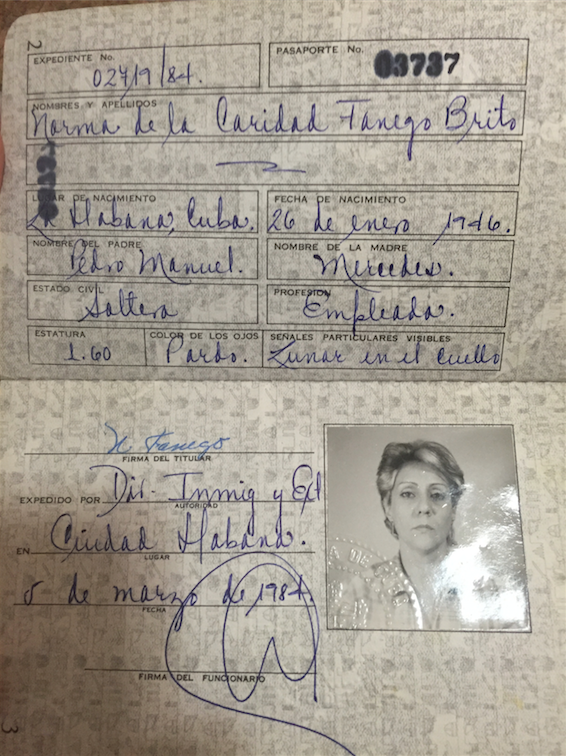

Norma Fanego’s Cuban passport

And it did. Four years later, he filed family reunification papers on their behalf and sent them money to pay for exit permission fees. Madelin Martínez packed some things in a 12-pound suitcase—less “than you would put in for a one-week trip”—and boarded a plane with her mother, her brother, her father and his second wife, and her widowed grandmother. Before they left, government officials scoured the house to make sure they did not take more belongings than the law permitted. “They counted the knives, the forks, the television,” she said. “They didn’t even let you take your photos, your watch, nothing.”

The decision to relocate was especially difficult for Madelin’s mother, Norma. It meant leaving the rest of her family in Cuba. True, she was with her children, but also with the family of the man she had been divorced from for a decade and his second wife. “I would have liked to have left by my own means,” she said, letting the thought trail off with raised eyebrows and a puckered forehead.

At dawn on May 9, 1984, the Martínez family arrived in Caracas. Madelin, by then 17, was amazed by the highway billboards advertising Coca Cola, Herbert Compote, and Mavesa Butter. “In Cuba all the signs said “Fidel” or “Martí” or “El Che Guevara,” she said. He first trip to a supermarket made her “dizzy,” she said, “with the amount of food and cans one besides the other.”

By the time the Martínezes arrived, Venezuela was receiving its third of five waves of Cuban émigrés. The community had grown to 13,000 with about 7,000 immigrants arriving during the period between 1978 and 1989. They were mostly former political prisoners and their largely lower middle class relatives. Among them were also some 900 travelers of the Mariel mass migration, which a sharp economic downturn in Cuba propelled in 1980. At that time, thousands of Cubans asked the Peruvian embassy for asylum and Castro allowed anyone who wanted to leave Cuba to do so.

In Caracas, the family moved into Reinaldo and his wife’s the two-bedroom apartment in downtown Caracas. Rolando and his new wife promptly found work as janitors in a residential building. Soon, Rolando was able to resume his career as a draftsman. Madelin and her mother Norma took jobs as hairdressers at Sandro, a popular salon in the middle-class neighborhood of Chacaito. Through a co-worker, Madelin met her future husband, Javier Belloso, a Venezuelan who owned a computer accessories store.

Norma Fanego’s Venezuelan passport

Twelve years later, everything changed. After a bewildering night of gunfire and explosions, Norma saw Hugo Chávez on television for the first time, along with the rest of the country. This was just before he went to jail for a failed coup against President Carlos Andrés Pérez. Chávez, wearing a red Castro-like beret, said “Comrades, for now we didn’t meet our objectives…I accept in front of you the responsibility of this Bolivarian military movement.”

Pérez’s successor, President Rafael Caldera, pardoned Chávez. Already there were rumors that he would soon make a run for the presidency. Indeed, he visited Cuba in 1994 to start planning his 1998 presidential campaign with Castro’s help.

Norma began to obsess about a Cuban déjà vu and two years later, decided to leave Caracas, a good four years before Chávez was actually elected. She packed up her and Reinaldito’s stuff. By then he was in the thrall of young local drug addicts, and needed out anyway. She moved with him to Miami on tourist visas. Once there, without working papers, she began working under the table, sweeping the floors of salons. Both she and her son were granted residency the following year as part of the Cuban Adjustment Act. Soon after, she obtained a hairdresser licence and resumed her profession doing cuts, blowdries and hair color.

Nonetheless, she was consumed with anxiety and bouts of depression. She had several minor car accidents and over the next five years, found it so difficult to concentrate at work that she went on disability.

“I was in a crisis,” she said. “All I did was cry. I didn’t know where to go. I wanted to go back to Venezuela, I wanted to go back to Cuba.” She mentioned her son. He died in 2014, in his late 30s. The details were still too difficult for her to discuss.

“I have pain inside me. I have struggled with the changes of one country to another,” was all that she would say.

Mijita, don’t forget to talk in there about what happens to you when you migrate. Explain it, tu sabes? When you migrate to any country in the world, even if you are able to do well financially, you stop being you. You understand? Sometimes I ask myself, what am I?” she said. “Cuban? Venezuelan? American? I am none of those.

A study of migration psychology prepared by American Psychology Association found that when immigrants experience mental health difficulties, it is usually related to the immigration experience. They call it “acculturative stress,” a condition that may cause depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder. The study also found that the age of a person when the migration takes place “shapes how the migrant unfolds in the new society.” Assimilation for those closer to retirement age, like Norma, is always harder.

She walked me to the door of her apartment. “Mijita,” she said when I turned around to leave, “don’t forget to talk in there about what happens to you when you migrate. Explain it, tu sabes? When you migrate to any country in the world, even if you are able to do well financially, you stop being you. You understand? Sometimes I ask myself, what am I?” she said. “Cuban? Venezuelan? American? I am none of those.”

But Madelin Martínez stuck around in Venezuela for another 21 years after her mother’s flight, and long after 1999, when she and her father first confirmed their suspicions about Chávez’s intentions. Together, they were watching one of his first speeches as president on TV, one in which he said that Venezuela was swimming towards the “sea of happiness.” They gave each other a look.

“You see,” her father remarked at the time, recalling the phrase from another dictator’s mouth. “This guy is going to do the same thing as the huevón de Fidel.”

Madelin didn’t ignore the unmistakable links between the Castro regime and the Venezuelan government. But it was hard to make the decision to leave. Her family was well established in Caracas, where since 2007, Madelin owned her own salon, where we met once in December of 2015, two months before she left the country and four months before our second encounter in Miami.

By then, the underside of the Bolivarian Revolution was inescapable. Her clients were complaining about how long they had to spend in supermarket lines to buy toilet paper and trying to figure out where the rumor mill said one could buy cooking oil. They brought their own hair products imported from abroad because it was impossible to find them in the city. The price of a mani-pedi was a third of a monthly minimum wage. “It is, I would say, like Cuba in color,” Madelin said in between the noise of the blow dryers, “Not as bad as was Cuba, but very similar.”

On the morning of August 29, 2015, Madelin, her husband Javier, and their youngest child, Christian, left Caracas and landed at Miami international Airport in the evening. Madelin showed the immigration officer her renewed Cuban passport and said that she wanted to adhere to the Cuban Adjustment Act.

The family was led to the Homeland Security room. They sat for hours. Madelin was anxious. After five hours of thorough questioning, document scanning, and fingerprint recordings, the officer granted them parole and explained the steps to follow from that point on.

It was almost midnight. Their daughter, Melanie, a student at Miami Dade College, had already gone through the parole process a year earlier and was waiting for them outside the airport. She and Madelin broke into tears when they hugged. They had not seen each other since Christmas.

From the taxi, Madelin called her own mother, Norma. “She was crying so much my poor mami.”

Norma was thrilled to have them nearby at last. It put her more at ease. Nonetheless, she said, “the damage is done, the emptiness is there.”

As for Madelin, leaving Venezuela brought a new set of hurts “because I truly valued the country even more than my own and, well, it turns out that the same thing happens to me again.” She nodded and looked down.

“After achieving all that I did in Venezuela, how am I going to do it all again, now at 52 years old?”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate