Sandinista Venezuela

I was a solidarity activist in Nicaragua in the 1980s. I've seen this movie before.

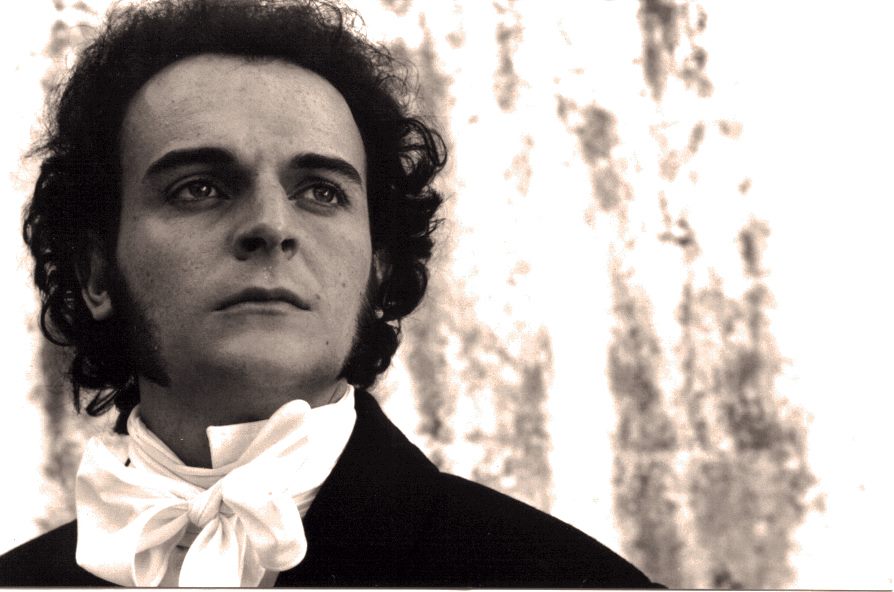

Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega (right) and his Venezuelan counterpart Nicolas Maduro stand in front of a picture of late Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, during a summit in Managua on June 29.

Back in 1987, when I was a young and idealistic solidarity activist, I spent a number of months working as a translator in Managua, Nicaragua. The high point of my life was the banquet I had every night—in my dreams. Like all the “Nicas” I spent my days hungry, but that’s what gave me such a great appetite for those elaborate dream meals. The country was hungry, and running on bald tires, and so was I.

I was getting around on a beat-up old Yamaha motorbike. One day it finally gave out and I had to take it to be fixed at a local “shade-tree” mechanic. Instead of washers on the bolts he used coins he had drilled out through the center: it was just cheaper. The guy spent his days drilling holes right through the head of Sandino. It’s an image that came back to me on my last trip to Venezuela in 2013 when I had my “aha” moment picking up cast off coins around a bus stop. All at once, I could see where this whole Bolivarian process was going. I’d seen it before.

Price controls, skyrocketing inflation, a refusal to discuss collective contracts or raise wages enough to cover even basic living expenses, an unholy mess of policies resulting in long lines for scarce products that could be bought and sold on the black market, making informal employment was the only way to survive. Venezuela? Yep, but also Nicaragua under the Sandinistas.

There are, of course, real differences, and they’re not negligible: Nicaragua doesn’t live on top of a lake of oil, and the economic war it fought through the eighties wasn’t just propaganda smoke to mask government ineptitude: it was real. If people like me travelled south in solidarity with the revolution it’s because Nicaragua faced a real embargo with real sanctions and a real war with real (“Contra” or “Comando”) soldiers doing real economic sabotage under real CIA tutelage.

Did those things help bring about the Sandinista’s spectacular economic implosion? They no doubt played some part. Were they the determining element? We loved to think so back then. But today, we know better: it was the Sandinistas’ incredibly misguided Economic policy that crushed the economy. And it’s the Venezuelan experience of the last five years that proves it.

By the end of the Sandinista Revolution, socialist economic policies were built around wage freezes, price and currency controls. The result? 30,000% inflation and widespread shortages. Venezuela, applying a broadly similar policy mix but with only a rhetorical, rather than a real, economic war, is heading in the same direction.

János Konai wrote a classic book showing how socialist policies applied in all kinds of different circumstances produces the same results. It’s akin to what you might learn in sophomore chemistry: when you put similar ingredients together in similar amounts, you get similar results. And the ingredients, amounts and results of socialism in Nicaragua and Venezuela were strikingly similar.

New York Times reporter Stephen Kinzer wrote in his memoir, Blood of Brothers, of those good ol’ days that “It was never possible to know what item one might be seeing for the last time in Nicaragua. First cookies and snack foods disappeared from the marketplace, then breakfast cereals…the most commonly heard expression in Nicaragua during the 1980s was ‘No Hay,” meaning “There isn’t any.”

Interviewing the manager at the plastic bag manufacturing plant (since EVERYTHING, including sodas, came in plastic bags), Kinzer asked why the state-owned Plastinic factory only produced at 50% of its capacity. Well, there was the scarcity of plastic pellets, mainly from Bulgaria, that came in irregularly as donations. But there was another factor, according to manager Roberto Gómez.

“‘There is a lot of absenteeism,’ Gómez explained. “Salaries are so low that people don’t bother to come to work. Trained technicians and engineers quit because they can make more money selling peanuts at the stadium than working here. Normally only about half of our employees ever show up, so the factory never comes close to producing at full capacity.’”

Kinzer goes on to describe a situation that perhaps most Venezuelans will recognize:

“The price of plastic bags, like the price of most other essential items, was set by the government. But because supply never met demand, and because the bags were so essential, eager consumers were willing to pay several times the legal price. A thriving black market developed, fed in part by shady middlemen with contacts inside the plant.”

Can you say “bachaquero”?

Nicaraguans called it “bisnes.” Kinzer tells us that “none of the repeated efforts to combat bisnes came close to succeeding.” Not the raids on the markets, nor the nighttime police illegal-stall-demolition squads in the markets, nor the fences erected around illegal vendors, which were quickly pierced and penetrated by those in bisnes.

Bisnes was so profitable that otherwise conservative farmers jumped in to get a piece of the action, encouraged by bluntly stupid government policies. Sandinista supporter Phil Ryan, author of The Fall and Rise of the Market in Sandinista Nicaragua, says that in 1984 the state was “paying bean producers c$8, putting out c$2.75 for storage and transportation costs, then selling the pound of beans to consumers at c$4, leading to the extreme of producers selling all their beans in order to repurchase them more cheaply from the state marketing agency.”

The shortages that inevitably develop in an economy under price controls meant lost productivity and long, long lines outside the supermarkets. Ryan writes that “by abandoning market-determined prices in favor of cost-determined ones, without putting in place a rationing scheme, the [Plan 80, first Sandinista economic plan] was essentially opting for “rationing by queues” and its attendant “sellers’ [“bachaqueros’”] market.” These “queues” or colas perversely provided higher-paying jobs as people poured out of the official job market where wages were also controlled, and flooded the unofficial “free labor market.” In addition to “speculation in beans,” Kinzer notes – and stop me if you’ve heard this one before – that “enterprising people in cities found entirely new ways to earn money, such as hiring themselves out to wait in lines for other people who were slightly better off.”

And what happened in those long lines portended what was to come for the country just a few years later, in 1990. Any astute observer could have read those lines like yarrow sticks, and Kinzer gave a hint:

“As people waited in those interminable lines, and as they cursed water shortages, blackouts and other deteriorating public services, their thoughts naturally turned to those responsible. After a period of years living under such conditions, many began to tire of explanations that had to do with American aggression and, quite naturally, began to blame the Sandinistas.” The Vanguard, it seems, was living “flamboyantly and in luxury,” and this “permanently alienated many Nicaraguans.”

The worst kink in this story is that the Contra war, the embargo, and much of the economic misery had all been quite avoidable. “During the Carter administration—the FSLN’s first eighteen months in power—the United States was the world’s most generous donor to Nicaragua, providing $118 million in direct aid, encouraging international loans of $262 million and supporting large adjustments in debt,” wrote Roger Miranda, who for years served as secretary and right-hand man to “Number Two,” Humberto Ortega, brother of President Daniel Ortega.

In The Civil War in Nicaragua, Miranda noted that the US had cut off aid to the Somoza government of Nicaragua and the government of neighboring El Salvador, hoping to defuse the violence in the region. When the Sandinistas took power, they immediately began to funnel arms to other leftist guerrilla groups in Central America, hoping to establish an eventual Castro-Communist Isthmus. That didn’t go over well in Cold War Washington and Carter was legally obligated to end aid to Sandinista Nicaragua as a result. The Reagan administration sent Thomas Enders to Managua to negotiate a peace agreement in which aid would be reinstated if the Nicaraguans would end arms shipments to the guerrillas in El Salvador (FMLN).

According to Miranda, despite “three detailed proposals” and two follow-up phone calls from Thomas Enders to the Sandinistas, the FSLN Directorate never responded. Instead, Ortega and other Sandinistas went to Havana for advice. After Ortega recounted the details of the meeting, Castro told him, “Don’t negotiate.” Instead, less than two months later, “Daniel Ortega launched a bitter attack against the United States at the United Nations and the truce was off.”

Again, the parallels with Venezuela are stark. Remember the Clinton administration’s offer to send humanitarian assistance following the 1999 floods, and Chavez’s very public rebuke? Care to bet whether Havana had a hand in that?

Back in Nicaragua, “peasants, workers and businessmen were frustrated by the web of regulations, incompetence, inefficiency, curtailment of incentives, declining living conditions, limitations on property rights. All contributed to migration to the cities, the expansion of slums in Managua, the growth of a black market, and strong rural support for and involvement in the Contras,” Miranda wrote.

In the end, the CIA found a ready-made army in the peasantry, who made up 96% of the Contra army that, at one point, ruled with impunity over half of the country. The war, the destruction of the country, its infrastructure and its economy where “per capita GDP had fallen to roughly $300 annually, lower even than that of Haiti,” were all the result of the arrogance of a vanguard elite, policies drawn up in Moscow and Havana, and an avoidable war.

When the Sandinistas were in power, the Cold War and Socialism appeared to be permanent fixtures on the political landscape, so it’s understandable that they were gullible enough to follow Castro’s catastrophic advice to confront any American overture, and take up a Soviet model for their economic plans. But given the end of the Cold War, the collapse of socialism, the discrediting of Castro and the failure of Sandinismo, what excuse do chavistas have for, as they say, repeating the same experiment and expecting different results? Isn’t that the definition of “insanity”?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate