Economic war (a real one)

What do you call it when a country throws its military assets behind a campaign to bully and intimidate a much smaller, poorer neighbour for the purpose of spooking away foreign investors and preventing it from carrying out strategic investments?

If the words “Economic War” are to mean anything, shouldn’t they mean that?

This post is a call to get real: what’s happening on Venezuela’s grandiloquently self-styled “fachada atlantica” (the eastern border it disputes with neighboring Guyana) is nothing but an attempt to give off-shore oil investors in Guyana cold feet.

This isn’t the prelude to a war, or an invasion, much less some adolescent fantasy liberation of a long-lost corner of the patria. It is just the mindless bullying of a tiny, poor country by its larger neighbour in some dick-swinging display of primate dominance. Nothing more, nothing less.

The problem is that we Venezuelans are poorly positioned to grasp this, because we approach the Essequibo dispute through two generations of hardcore, know-nothing chauvanist propaganda. A toxic mix of wounded pride and demagogic posturing pioneered by Acción Democrática made this claim so politically addictive even chavismo couldn’t jettison it overboard.

At its center is the idea that the 1899 arbitral ruling that set Venezuela’s eastern border is, in some real sense, “en reclamación”: subject to a live international dispute that could result in Venezuela “regaining” sovereignty over the Western Bank of the Essequibo River.

This is Grade A, industrial strength nonsense.

The story is long – 120 years long! – but here’s the gist.

In 1895, the British decided to make a play for the navigable mouth of the Orinoco River – all the way out to Curiapo and down through Guasipati. But the U.S. balked, realizing that losing control of the Orinoco’s shipping lanes would turn eastern Venezuela into a new, de facto British Colony in the Western Hemisphere.

People don’t realize it, but the UK and the US came close to war over this. War was averted, though, when the Brits, under US pressure, agreed to subject the dispute to arbitration through a panel convened in Paris and empowered to make a binding and final decision.

You’ll note Venezuela is largely missing from this narrative, and for good reason: in 1895-1899 Venezuela was more or less a failed state. Guzmanismo had collapsed, but the Andean dictators hadn’t come on the scene yet. The official government in Caracas controlled little beyond the customs house in La Guaira. Venezuela’s extreme weakness is one reason Britain was making a play for its territory. Either way, Caracas was largely a bystander in the Great Power maneuvering in the late 1890s, but it agreed to go to Paris nonetheless.

Now here’s the bit they don’t teach you at school: the panel, in effect, sided with the Americans. It granted Venezuela the strategically crucial control over Orinoco river shipping, then tried to mollify the Brits by awarding them a bunch of virgin jungle. Nobody wanted virgin jungle. That wasn’t the point. As far as anyone knew, it had no value.

Still, un mal arreglo es mejor que un buen pleito, so the Brits accepted the ruling, as did everyone else, including Venezuela. War was averted, case was closed.

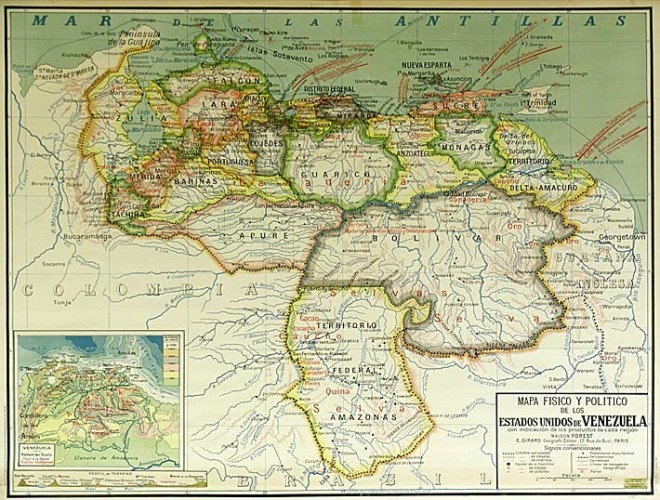

For sixty-three years following the award, that was that. Official Venezuelan Maps showed the Essequibo territory as belonging to Britain, and if you know anything about international law, you probably know that accepting territory as belonging to someone else in official maps puts a serious dent on any attempt to convince people that, oh wait, that land is mine.

Estados Unidos de Venezuela, 1930

Years later, some evidence came out that suggested the Brits were up to some hanky-panky at the Arbitration Panel: specifically, that they cut a deal with the Russian judge privately to try to improve the settlement they would get. Only trouble is that by the time the memo in question came out in 1949, all the principals were dead. There was no chance to cross-examine them, to check and match recollections, to really make sure Severo Mallet-Prevost’s version held up.

But even if the allegations in Mallet-Prevost’s posthumous memo are right, by the standards of 19th century Great Power diplomacy the infraction is the equivalent of speeding up when you see a traffic light turn yellow – perhaps not exactly the way the rule-book says you should do things, but c’mon.

Think about the international context. At roughly the same time the British were settling the Western edge of their South American colony via undue influence between gentlemen in a Paris diplomatic salon, they were settling the Northern edge of their South African empire by wantonly machine-gunning Boers into smithereens and rounding the survivors up into concentration camps.

You want to talk about dodgy borders? Fourteen years earlier, sitting around a conference table in Berlin, a handful of European diplomats had carved up the whole of Africa, drawing random lines on a huge map over any number of places none of them had ever seen. That’s a dodgy border!

What’s staggering is how Venezuelans politicians act as though some enormous, unprecedented violence had been perpetrated against the homeland in the arbitration without the slightest sense of irony. Guys, every 19th century colonial border was dodgy!

Ours was, if anything, more kosher than most. At least we had a formal process, and a big power fighting our corner. If we hadn’t had that, Guyana would probably share a border with Anzoátegui State.

The posture -universally adopted in Venezuelan political circles left, right and center- that the 1899 decision can be reversed or revised is a childish fantasy, at best, and a threat to world peace at worst.

I’m not exaggerating. Just glance through Wikipedia’s page on international territorial disputes: there are hundreds and hundreds of them, and quite a few of them involve countries better armed, more geostrategically salient than Venezuela and Guyana, and certainly some with better claims than ours.

A world where the 1899 Arbitral Settlement is open to question is a world where a hundred other, far bigger and much wrigglier cans of worms are open. It’s a world where Turkey and Greece are at each other’s throats over Tenedos, where India and China are on an escalation path to nuclear war over half-a-dozen contested outposts, where Bolivia’s claim on some prime sea-side Chilean real estate looks like a slam dunk, where Cambodia and Thailand are on a trip-wire to conflict over the Preah Vihear Temple, and an etc. as long as my arm.

An international system where a 63-year old settlement, long accepted by everyone involved, can be undone over a dead man’s memo is a wildly unstable and insanely dangerous international system. A world where the 1899 arbitration can be thrown out is a world you do not want to live in.

And it’s a world no international court would consider leading us into. If you doubt this, ask any of the heavy-chested defenders of our claims over the Esequibo: say, why don’t we go to the International Court of Justice in The Hague to settle this? Watch them balk at the thought of trying to convince a panel of impartial judges that Venezuela’s rightful eastern border is the Esequibo River. It’s a preposterous claim, and they know it.

These basic realities have gone so long without being said out loud in Venezuela, they’re a complete revelation to most people. What’s most disheartening about the current spat is the way the entire opposition leadership, having spent years towing the traditional chauvinist line, is stuck having to tacitly support Maduro’s abhorrent economic war on Guyana. Posturing that seemed cost-free at the time now comes back to haunt them: support Venezuela’s cowardly bullying tactics, or be a flip-flopper as well as a vendepatria.

At some point, somebody grown up is going to have to put his or her head above the parapet and say the blindingly freakin’ obvious: el Esequibo es de Guyana. Siempre lo ha sido. Siempre lo será.

At most, we can sabotage their very poor economy. Wantonly. Pathetically. To no end. And I guess that’s the plan.

But is that something the opposition should be applauding?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate