Suggested Sunday reading

Two great pieces from two friends-of-the-blog, both of them at Harvard University, both of them in Spanish.

Two great pieces from two friends-of-the-blog, both of them at Harvard University, both of them in Spanish.

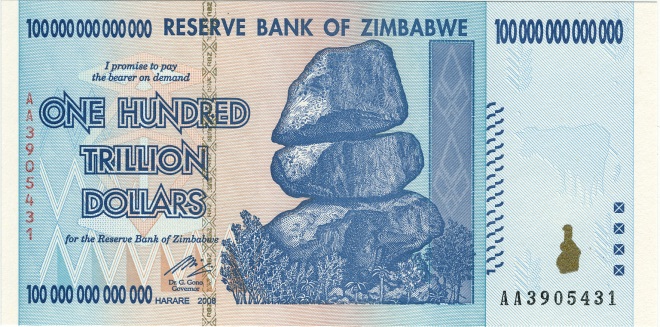

First off, Francisco Monaldi goes deep on hyperinflation in El Nacional. Francisco is lucid when discussing why this traumatic phenomenon occurs – governments basically print money out of control because they refuse to adjust to changing commodity prices.

Oil producers, however, rarely fall into hyperinflation because they can always devalue the currency, and since they are the only ones selling it, this quickly solves the government’s fiscal problems. Sure, there is a spike in inflation when that happens, but it goes away, unlike hyperinflation itself. Venezuela, however, refuses to devalue.

This was the part that called my attention:

“But, why have they not dared devalue the official exchange rate? Probably out of fear of the political cost and its impact on electoral dynamics. Maduro was traumatized by the fact that the devaluation prior to his election in April of 2013 almost cost him his job.”

I agree that Maduro’s election has marked him deeply, but I’m not sure that we can chalk it up to devaluation. In fact, I didn’t even remember that the government had devalued prior to that election – as far as I recall, the devaluation happened in February, right? (I remember because I was finishing our book at the time, and Chávez died a few days after that) But it’s an interesting theory nonetheless.

What I liked about the piece was how it ended on an optimistic note. Historically, hyperinflation is so traumatic to a society that it sweeps away the governments that caused it, and the ones that come in do so riding on considerable political capital that allows them to implement many needed reforms.

Oh, we wish.

Another piece – this one not as recent – is by Jose Ramon Morales in Foreign Affairs Latin America, where he discusses Chávez’s legacy. I think Moncho, as his friends call him, has an effortless way of putting things, slipping in his arguments in a way that is not easy to do. (You may have noticed that by reading that horrible last sentence I just wrote):

Moncho’s main point is that Maduro is Chávez’s legacy: an economy that is crippled, and a government too paralyzed to do anything about it. The highlight:

Today, the biggest challenge to political stability in Venezuela does not come from the opposition, the bourgoisie, or the empire, but from the many dark factions that make up chavismo. For many years, internal conflict was placated with “Chávez’s finger,” the Solomon-like decision making of the final arbiter. Chavismo’s entire legitimacy was built on Chávez. Chavismo was built with an excessive dose of personalism, and this explains the secrecy of Chávez’s illness, as well as the importance of explicitly naming an heir. Part of Chávez’s legacy is, then, a government that only one in five Venezuelans support, and can only gain legitimacy by histrionically defending the late man’s “legacy.”

This is a topic we don’t discuss much – the absolute absence of a governing agenda in Venezuela. Other than repressing and holding on to power, is the government really doing anything to solve scarcity? Inflation? Crime?

No. Instead it whithers away its time collecting signatures against Obama.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate