¿Celacomió? Absolutamente não, meu amigo.

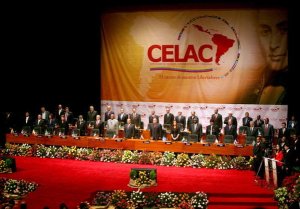

First off, credit where credit is due: chavista diplomacy deserves real kudos for some great optics at the Celac Launch summit still going on in Caracas today.

First off, credit where credit is due: chavista diplomacy deserves real kudos for some great optics at the Celac Launch summit still going on in Caracas today.

Those photos of dozens of Latin American and Caribbean heads of state coming to his capital to join an initiative he’s held dear for so long are a big propaganda coup for Chávez. They put him in the role of elder statesman, almost, and certainly show how counterproductive the U.S.’s ongoing hardline against Cuba in hemispheric affairs has been. I have to imagine the Casa Amarilla is thrilled with all this, and they have a right to be.

(I’ll save for another time the rant about the way the optics in Caracas this week highlight the insanity of the Arria-cho strategy of painting Chávez as an utterly isolated, beyond-the-pale, Assad-like figure dodging the prosecutors in The Hague…just think, while Arab league summits was busy kicking Syria out, Chávez was preparing to host the meeting to create the Latin League!)

Still, it’s worth pondering the extent to which Chávez’s hemispheric ambitions have been downsized at this point. A decade ago, the goal was to lead a block of states to supplant market-based approaches to economic development with a state-led socialist development model. Today, Chávez’s biggest diplomatic coup in years consists in hosting a series of governments engaged in successful market-based economic development experiences, but without a U.S. delegation in the room.

Partly, I think, this stems from a fundamental misunderstanding about who the real rival was. Chávez flatters himself thinking he was engaged in any kind of meaningful contest with the Americans. His real rival was the superpower closer to home: Brazil. Or rather, the real threat to his vision for hemispheric development was a successful Social Democratic Brazil becoming the go-to model for other governments in the region.

Today, Brazilian soft power – the power to make others want to emulate you – is running extremely high. When new left-wing governments come to power in the region, the model they instinctively turn to is the Brazilian model. The contrast between Brazil’s thriving economy, falling inequality, rising middle class and vibrant democracy and Venezuela’s increasing oil dependence, social stagnation and democratic involution is too plain to require much elaboration. So, even a guy with a long track record of leftist extremism like Ollanta Humala can’t really resist the lure of Brazilian soft power.

And so the presidents will come. They’ll make their speeches. They’ll eat their state dinners. They’ll sign their grandiloquent declarations. And then they’ll go home to administer a model of development that’s diametrically opposed to the one their hosts wanted to see become dominant in the region.

Which, I suppose, is why Foggy Bottom is entirely relaxed about the Celac launch. The gringos may not be in the room, but neither do they really need to be. Given the overwhelming preponderance of Brazilian soft power in the region, Celac doesn’t pose any kind of credible threat to U.S. interests.

Latin America just isn’t going to abandon a successful development model and adopt a patently failed one because a bunch of speeches were made in Caracas.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate