The forgotten trailblazer

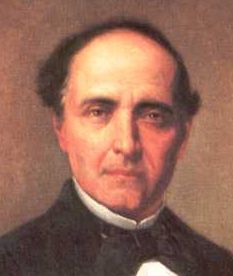

Juan Cristobal says: Take a look at this picture. Quick: can you tell me who this man is?

Juan Cristobal says: Take a look at this picture. Quick: can you tell me who this man is?

If you can’t – and I bet you can’t – stop to ponder the fact that you’ve failed to identify Venezuela’s first popularly elected president, Manuel Felipe de Tovar.

No reason to feel bad. I had no idea who he was either until pretty recently, when I picked up a copy of Rafael Arráiz Lucca‘s “Venezuela: 1830 a nuestros días.” The book is a compendium of the major historical events of our history as a free nation, almost by necessity broad in scope and yet shallow in the treatment of most topics. It was perfect for me.

I picked it up half embarrassed, realizing the last time I put any sustained effort into learning Venezuelan history, I was a stonewashed Maracaibo teenager. Reading the book, it was remarkable how some things seemed as familiar as daylight. But I also stumbled on a few surprises.

Case in point, the man in the picture. Manuel Felipe de Tovar was the true precursor of Venezuelan democracy, but he’s now almost completely forgotten. Here’s what Arráiz has to say about him:

“In accordance with the Constitution passed in 1858, elections were held in April of 1860, and the winner was Manuel Felipe de Tovar, with 35,010 votes, for the 1860-1864 constitutional period. No immediate reelection was allowed. Pedro Gual was elected Vice-president for two years, with 26,269 votes… For the first time, Venezuelans directly elected their leaders, and they did so in the midst of a cruel war that had already cost thousands of lives and was sowing the country with misery and desolation.”

It’s strange. Somehow my brain had assimilated the notion that we had to wait until 1948 to elect a President for the first time, a certain Rómulo Gallegos. Could I have been wrong all along? Was I simply the victim of my own ignorance, or was this all an adeco fairy-tale, further proof of their penchant for rewriting history? Could it be that Arráiz got it wrong?

No, it’s true, Tovar was the first. Sure, he was elected on the basis of a limited franchise, but then, so was Jefferson. Even the Chávez government acknowledges he was the first, which is strange since Tovar was elected as a Paecista, and we know how much Chávez loathes José Antonio Páez. (Recent reports suggest the government even desecrated Paez’s grave.)

I wonder how Tovar’s achievement was received in Venezuela’s mid-XIXth Century political circles. Being an elected, civilian President in Venezuela in those days had to be quite a handful, calling for equal measures of luck, naiveté and chutzpah. Tovar must have been a dreamer of gargantuan proportions to think he could pull it off.

Elected in the middle of a notoriously cruel civil war, Tovar faced serious military and economic challenges from day one. The government was bankrupt, so he instituted our first income tax. He freed up imports of scarce agricultural products and froze the salaries of government employees. He pardoned some political prisoners while waging war against guerrilla-style militias determined to overthrow him. The complaints about the civilian Constitution not being strong enough to deal with the rising insurgency grew louder by the day, and they eventually paved the way for the subsequent Páez dictatorship that ended Tovar’s stint after only 13 months in power.

I’m no expert on Venezuelan history, I’m just a guy who read a book. But in the midst of the turbulence of the country’s early years, I found a lot that’s familiar.

To understand Venezuela’s beginnings as a country, it’s important to ponder the nature of those in charge at the time. The War of Independence was a traumatic military event. Contrary to popular myth, it was not won by a unified army with a clear line of command. Instead, it was waged and won by a semi-coordinated bunch of militias composed mostly of illiterate peasants, each led by its own caudillo. With rare exceptions, when I say “caudillo” I mean warlord.

Immediately following the war, the caudillos and their followers found they had to submit to a government in faraway Bogotá headed by an unelected President-for-life. Naturally, they pushed to break away from Colombia. After all, they’d had to cross the Andes to go free Colombians, Peruvians and the like; it’s not surprising they felt they were getting the short end of the stick having to bow to a bunch of snobs like the Santanders and Nariños of the world.

In spite of their disparate interests and personalities, they joined together and fought the common cause of secession. One of the movements they started was called “La Cosiata“, a derisive neologism for a group not unlike the recent Coordinadora Democrática.

Emboldened by their hard-won military victories, and drunk from the success in achieving secession from “Gran Colombia”, it’s no wonder chaos ensued. During the first thirty years of our existence, Venezuela endured one failed government after another. Constitutions came and went, as did the military coups. The only intermittent periods of relative calm came when Páez reluctantly made himself dictator and managed to quiet things down a bit. When circumstances allowed, he would retreat to either his farms in the Llanos or to New York, where he eventually died.

So the nation was built by a hodgepodge of ambitious latifundists-turned-generals looking to get rich quick, men who felt entitled to the spoils of war, perhaps understandably after risking their lives and their lands for the patriotic cause. Against that backdrop, it’s not surprising that the few attempts to establish civilian rule, institutions and a functioning state were utter failures. But they did exist.

The early history of the republic is dominated by all things military, while the exceptions such as the civil-minded Tovar or José María Vargas lie half-forgotten in the dustbin of history. It’s no surprise that Tovar himself was buried in a random Paris cementery instead of in our National Pantheon, and that instead of celebrating him in plazas or streets, we are quickly running out of boondoggles to name after psychopath-murderers-cum-half-failed caudillos.

But are we doomed to keep repeating that history again and again? Will bloggers 60 years from now be surprised to dust off a history book that informs them that Hugo Chávez was not the first popularly elected president, like their schoolteachers said?

Not at all. Because the remarkable thing about men like Vargas and Tovar is not that they failed, but that they ever had a shot. They saw disorder, yet they were bold enough to dream of a different country. That’s as much a part of our heritage as the caudillo strain.

Fast-forward 180 years and picture yourself in 2013. Suppose for a minute that Chávez leaves power.

After wiping the smile off your face, think of all the people, all the groups that are going to feel entitled to the spoils of victory: businessmen, students, politicians, unions, ex-PDVSA folk, the Plaza Altamira gang. Think of the effort it’s going to take to keep everyone’s interests at bay and put the nation’s interests first.

It would be easy to picture this and conclude, as many swing voters do, that while Chávez may be bad, the opposition is worse. It’s only natural for our fears to be confirmed by the intense tussling the opposition is currently embarked on. Is it any wonder, then, that Chávez plays on this fear with slogans like “No volverán“?

But the apparent anarchy in the opposition is not always real, nor does it necessarily imply that we are doomed to fail. Against Chavismo’s ambition to “get Bolivar’s dream right”, maybe we should oppose a decidedly more modest goal: vindicating Tovar. The civilianist current he pioneered is just as Venezuelan as caudillismo, and much, much more relevant in today’s world. We are Doña Bárbara, but we are also Santos Luzardo.

It’s useful to keep this in mind next time we see the opposition behaving like a sack of cats with no clear goals in sight. It takes a lot of effort to be organized when bochinche is embedded in our DNA. The thing to remember is that it’s not just bochinche that’s in there: the determination to do away with caudillos and bring the country together behind an elected civilian on the basis of the law is just as embedded in us, just as Venezuelan. Which is why we should celebrate whenever civilians manage to talk out their differences and bring us closer to realizing that vision.

So next time you feel a vein is about to burst at the sight of Saady Bijani, spare a thought for Manuel Felipe de Tovar, a man who, irony of ironies, took the oath of office one April the 12th. And if you dare to dream that yes, we can overcome our history, take comfort in the fact that greater Venezuelans have harbored the same dream when facing even longer odds than us.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate